The Mauritshuis has teamed up with Dutch researchers to probe just what happens in our brains when we view art in person, compared to seeing a reproduction. It’s the museum’s first research into emotional responses to art—and the results will come as no surprise.

“We see reproductions of famous paintings everywhere, particularly Vermeer’s Girl With a Pearl Earring. This study has shown once and for all that a visit to the Mauritshuis or another museum has much greater emotional value,” said museum director Martine Gosselink in a statement.

The study concluded that seeing art in person elicits an emotional response that is 10 times stronger than viewing a reproduction. Using electroencephalograms (EEGs), researchers find that looking at original works such as Johannes Vermeer’s famed c. 1655 portrait elicit a more powerful positive response than when people view reproductions of the work.

Besides Girl With Pearl Earring, the research also deployed other masterpieces—referred to as “benchmark paintings”—including Rembrandt’s Self-Portrait (1669) and The Anatomy Lesson (1632), Vermeer’s View of Delft (c. 1660-6), and Gerard van Honthorst’s The Violin Player (1626).

Johannes Vermeer, Girl with a Pearl Earring (c. 1665). Photo: Sepia Times/ Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

The research was commissioned through neuromarketing company Neurofactor, which engaged Neurensics, an independent consumer neuroscience research agency. The study asked 10 participants to don EEG headsets and eye trackers and follow a specific route around the museum where Girl With the Pearl Earring and the four other paintings were hanging. The same 10 individuals were then shown three reproductions of the paintings in the Mauritshuis library, while still wearing the headset and trackers. Another group of 10 test subjects, also wearing the same gear, looked at reproductions first, then followed the same route as the first group through the museum.

A second phase of the study consisted of a functional MRI (fMRI) brain scans performed on 20 participants as they viewed reproductions of the paintings from the museum. Of the 20 test subjects, five participated in the first phase.

A participant in the Mauritshuis’s study. Photo courtesy of the Mauritshuis.

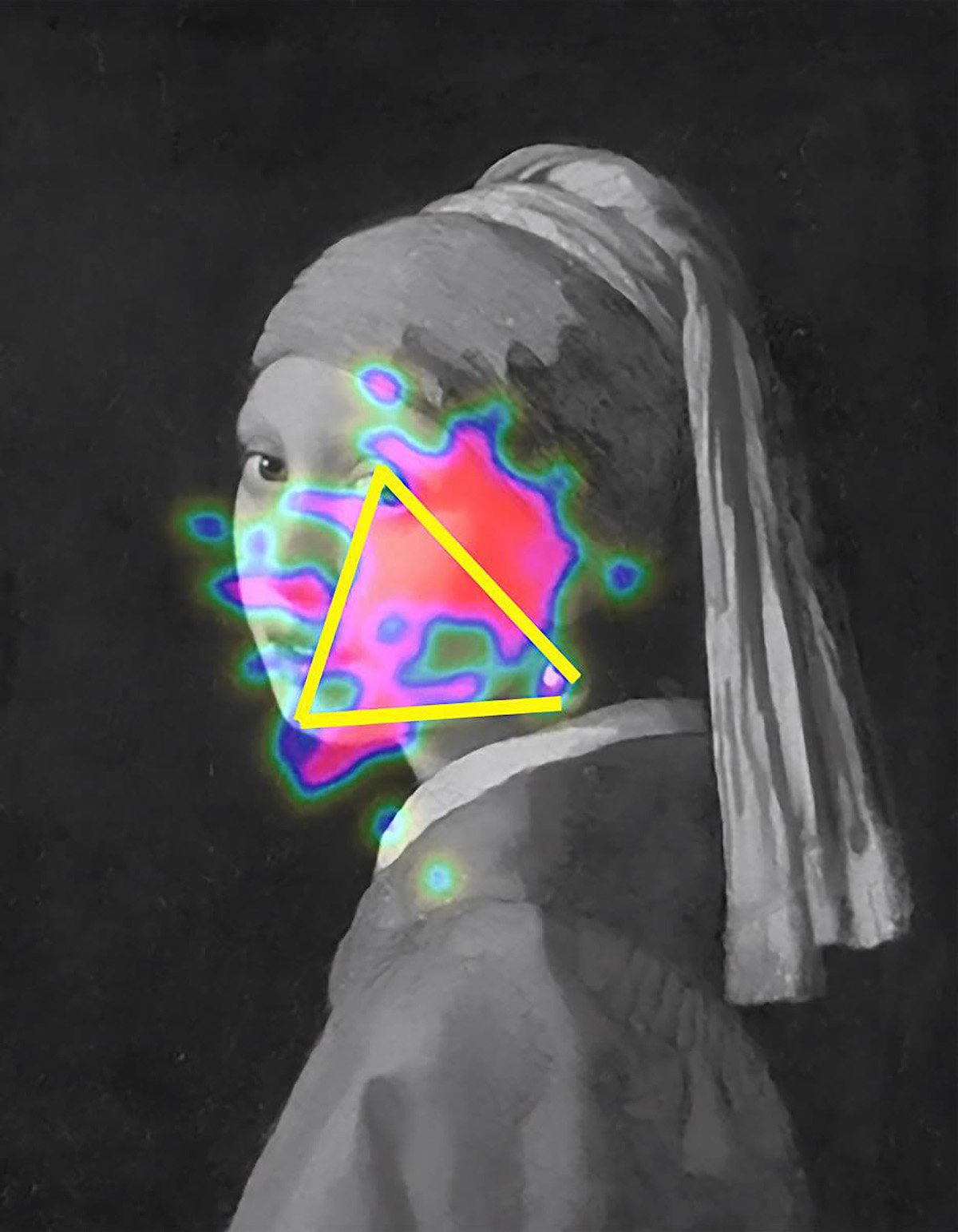

In addition to the enhanced emotional response viewers felt when face to face with paintings, the analysis also identified how Girl With Pearl Earring especially captivated their attention. Notably, viewers tended to be drawn first to the Girl’s eyes and mouth, before they shift their glance to her pearl earring. The lone piece of jewelry then guides their eye back to the subject’s eyes and mouth. Researchers identified this triangulation—between eyes, mouth, and pearl—as producing a “sustained attentional loop,” which occupied participants more than any other painting in the study.

The sustained loop, said Neurensics’s co-founder Martin de Munnik, “is the factual explanation behind all kinds of opinions people had about the attention the Girl demands from us—an impact that is amplified when the work is admired in a museum.”

The study also found that when viewers engage with Girl, the most stimulated part of their brains was the precuneus, the region that controls attention shifts, episodic memories, and self-reflection. This result, the researchers noted, was again more pronounced with the Vermeer work, compared to the benchmark paintings.

“We live in a time when we are increasingly confronted with copies and interpretations of reality. You might think that real, genuine art or objects therefore become less important, but the opposite is true: real is actually becoming more important,” Vera Carasso, director of the Netherlands Museum Association, reflected in a statement. “How wonderful that this effect has now been scientifically demonstrated and can be seen in brain activity.”