Buildings bear witness to birth, death, and everything in between. They observe history through political upheaval, social reform, and countless changes in ownership and purpose. It is perhaps no wonder then, that so many contemporary artists explore buildings as containers of memory.

In these works, scuffs and scratches that mark interior walls become visual reminders of previous activity. Sometimes hazy interior spaces are recreated entirely from memory, highlighting the slippery nature of our view of the past. Within these works, the mind and its emotional content find form in architectural space.

Tolia Astakhishvili, recent winner of the Chanel Next Prize, combines personal and fictional memory with the reverberant past of her exhibition spaces. Her 2023 installation at Haus am Waldsee, for example, called “The First Finger (chapter II),” (it was part of a two-show exhibition with Bonner Kunstverein) contained echoes of the building’s history in wartime Germany, first housing a wealthy Jewish family, then passing into government hands, and finally opening as an art space. She does not spell out such specific histories within her shows, instead inviting the audience to contemplate the corporeality of architecture—and human impact upon it—in a wider sense. Her exhibitions are tricky, revealing layers of buildings that usually remain hidden, which involves adding her own structures made from materials such as drywall and cement. It is a form of simultaneous excavation and new development.

Tolia Astakhishvili. Photo: ©Mareike Tocha, Courtesy the Artist

“Layers of emotions can be found in the textures of building materials and the connections between spaces,” said Astakhishvili in a recent email. The Georgian artist recently opened “Result,” a show that includes numerous mediums, with fellow artists Maka Sanadze and Zurab Astakhishvili at LC Quesser in Tbilisi, Georgia. In the days after our interview, the gallery building was temporarily closed in solidarity with ongoing protests within the city. “Memories are deposited on the walls in the form of stains and sediments, in the paintings, photographs, drawings, and architectural elements that interweave,” said Astakhishvili. “Memory is a reservoir of things that are not forgotten and remain because there was a host for them to be kept in. There are shelves and hooks, niches and arches, corridors and entrances that hold the accumulated leftovers of the mind.”

Tolia Astakhishvili. Photo: ©Mareike Tocha, Courtesy the Artist

Astakhishvili’s work celebrates humans’ reciprocal relationship with architecture, in which our movements can be radically impacted by the built forms that surround and house us, while we also make an impression on them. “It’s been seen as common sense that architecture can influence us, but we also inhabit and change our environment,” she said. “I think it’s a very similar movement to what happens inside when physical and mental perceptions influence each other; physicality becomes an environment for the mind.”

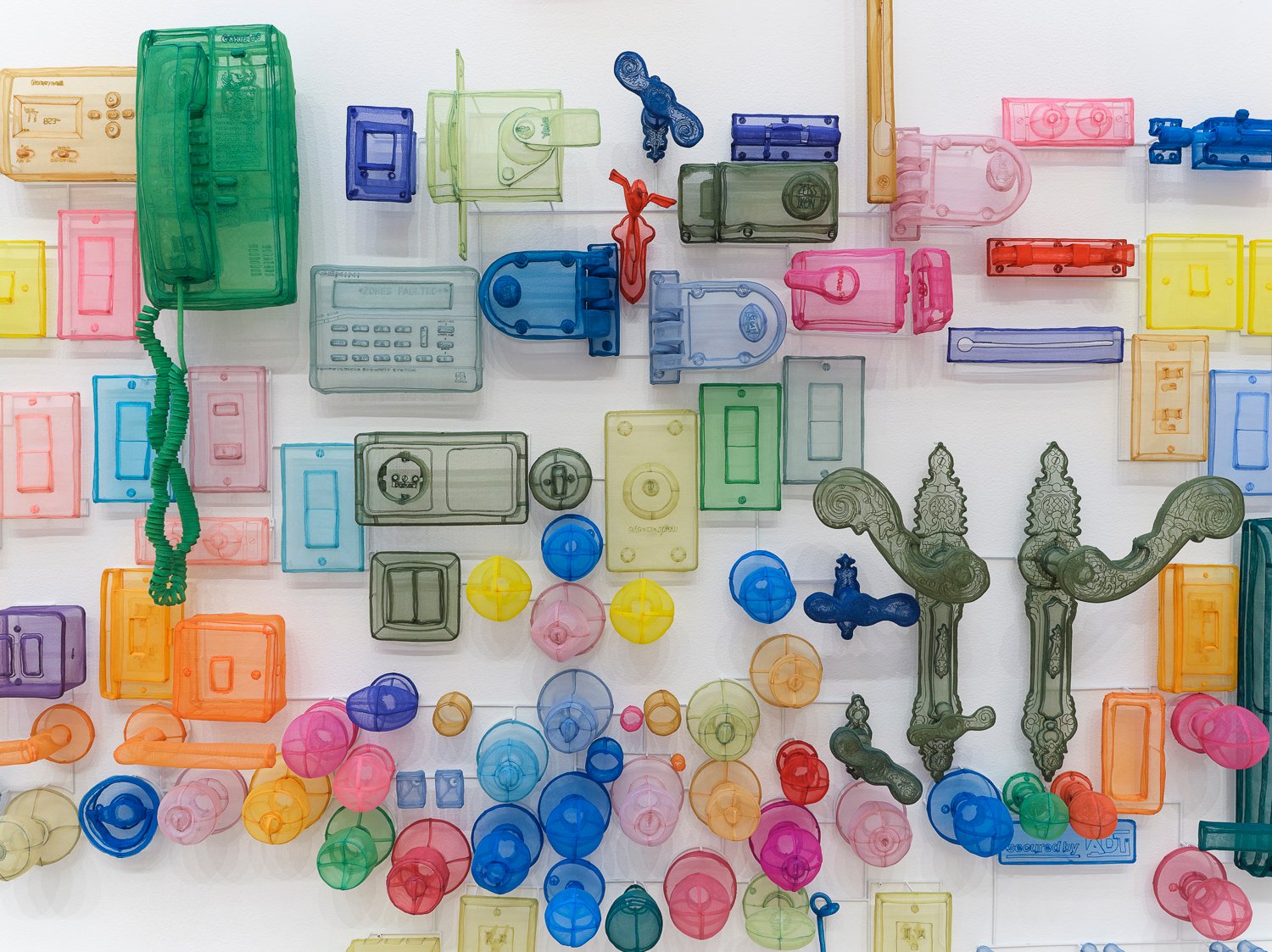

Do Ho Suh “The Shape of Time: Korean Art after 1989” Philadelphia Museum of Art (October 21, 2023 – February 11, 2024) © Do Ho Suh. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Seoul, and London. Photo by Tim Tiebout.

Though of a different generation, 62-year-old Do Ho Suh’s ethereal structures similarly call to mind the entanglement of mind, body, and built environment. The South Korean artist’s work is imbued with memory and nostalgia, often taking the form of colorful, transparent recreations of traditional buildings that look as though they could dissolve away. Memory here becomes entwined with loss, these buildings existing somewhere between physical form and disparate nothingness. Viewers might find themselves longing to walk through his buildings. The artist has previously addressed the slipperiness of memory, acknowledging that these remembered forms will differ from their originals. Their single color palettes, in bright blues and pinks or soft greens, exaggerate quite how warped these ideas of the past become. Like Astakhishvili, he presents buildings in a state of autopsy or partial disintegration, hinting at the possibility of connecting with the past, while knowing it will forever stay beyond complete capture.

Buildings take on a similarly ghostly presence in Mary Stephenson’s paintings. The British artist has previously depicted a sprawling domestic structure without any windows or doors, threaded through with long strips of fabric, called Baby Blue Door (2022). Many of her paintings utilize a limited color palette; Blue Stage (2024), for example, is so washed in the same deep hue that it takes a moment for the eye to tune into the steps and walls in the foreground. Themes of memory and grief are explored in these pieces, which evoke the act of half remembering the details while fully feeling the connected emotions.

Mary Stephenson, Blue Stage, 2024. Photo: Courtesy the Artist

“My paintings are cathartic playgrounds for me to explore my internal world in, and paint becomes the routing system to a feeling or memory,” said Stephenson in an interview. “Paint and color can instantly take you back to a distinct and vibrant memory. For me, memories are not always figurative structures, but are the feeling, temperature, tone, and hue of a room, the air between one internal window to another… [Buildings] are porous structures for the external world to be absorbed into.”

Hettie Inniss Potato Skins (2024). Copyright the Artist. Courtesy of the Artist, and GRIMM Amsterdam | London | New York.

Hettie Inniss also uses a restricted color palette in her dreamlike interior paintings. Red, orange, and yellow dominate the British-Caribbean artist’s canvases, creating fiery scenes that flit between solid form and ephemeral vision. Parts of her works are painted in intricate detail, while others are left vague and watery. “I use memory as a vehicle to comprehend space and my body within it,” the British artist said in an interview. “Architecture is a motif that flows throughout my work as it is what I recollect most vividly. How I feel within these spaces also becomes part of the work. Buildings naturally create a skeleton for my memories to exist within; experiences move between the tangible and abstract.”

Turin-born and -based artist Beatrice Bonino takes a slightly different approach to memory and space. She explores the potential for interiors to hold psychological residue through language. For her 2023 solo show “If I did, I did, I die” at Jacqueline Sullivan Gallery, the artist took inspiration from Frances Yates’s book The Art of Memory, in which she puts forth a mnemonic approach to architecture, for example, learning a speech by picturing oneself walking through a building as it is spoken, with the words becoming attached to different plants, objects, and other visual markers. Within Bonino’s exhibition, bows were used to attach long curtains over the window, signifying a physical attachment of her psyche to the space.

Beatrice Bonino’s Gallerina at Galerie Molitor in Berlin. Photo: Courtesy of the Artist and Galerie Molitor. Photos by Marjorie Brunet Plaza.

None of these artists present memory as a way of understanding of the past. Instead, they highlight how the past is richly woven through our physical world while remaining tantalizingly outside of our direct vision. They excavate and uncover, evoking a deep need to feel the past contained not just within our bodies and minds, but the various spaces we move through and inhabit.

“Memory is a word that can be overused, it contains so much,” considered Astakhishvili. “It pulls you and moves you in many directions, it takes you to other times and will displace you from here and now. This displacement from here and now [and] or the connection to memory, it is the mental bridge.”