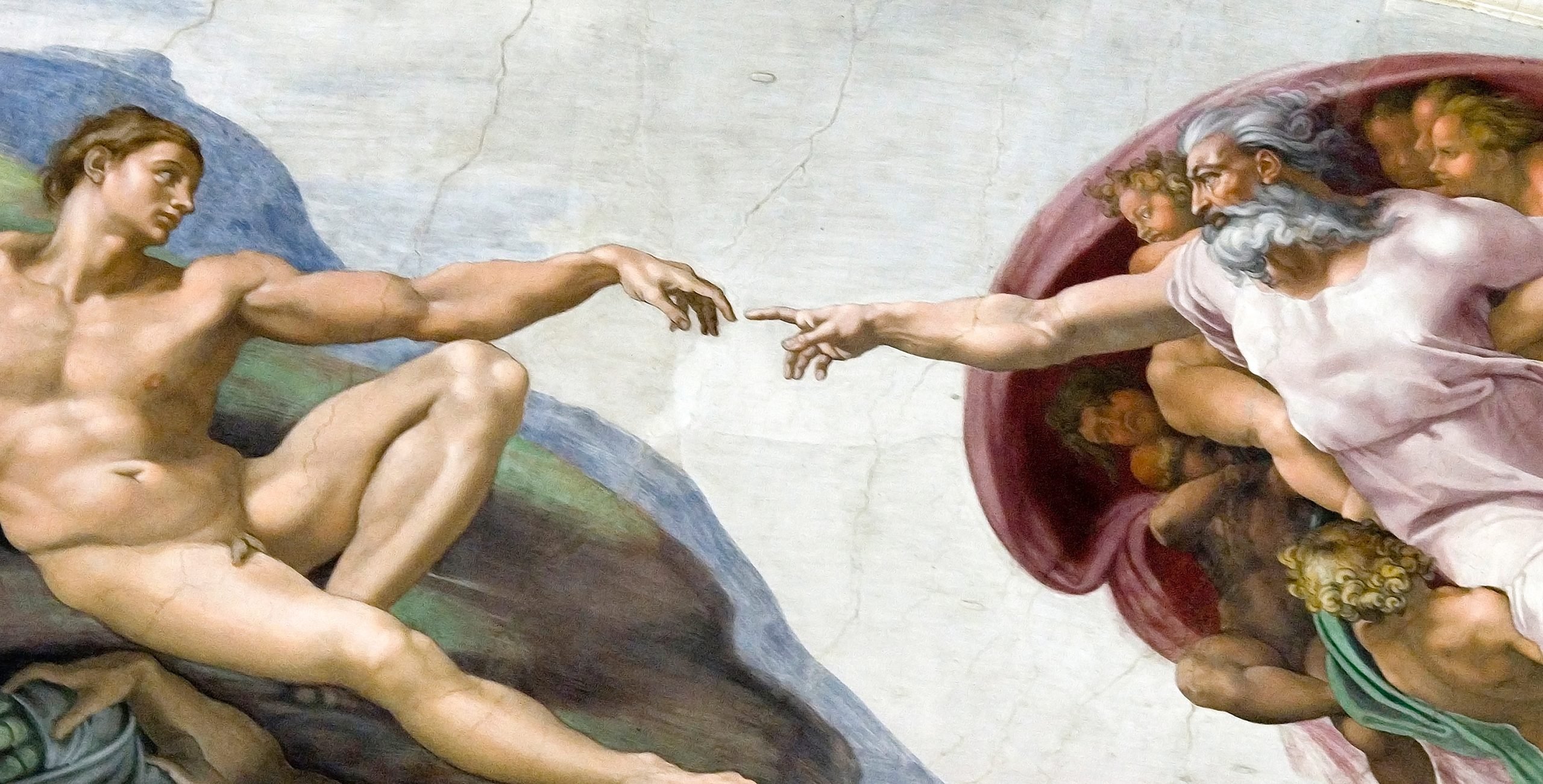

It’s been half a millennium since Michelangelo finished painting the cavernous Sistine Chapel. Experts are still discovering hidden symbolism throughout his handiwork. Their latest revelation? The Renaissance master may have included a woman battling breast cancer, which is typically mistaken for a modern disease. Eight European art historians and medical experts have published a study in The Breast journal on their use of iconodiagnosis, a rising interdisciplinary field that pinpoints medical conditions in significant artworks.

“[Iconodiagnosis] may teach us both about diseases in history (and possibly their evolution and management in historic populations), but also gives us an insight how a ‘diseased status’ may have been ‘used’ as a stylistic metaphor in ancient times,” Andreas G. Nerlich told me on behalf of his team via email.

Michelangelo painted the Sistine Chapel predominantly between 1508 and 1512. His efforts sprawl over the Chapel’s ceilings and walls, recounting scenes from the Bible’s Old Testament. The figure at the center of this month’s study hails from “The Flood,” one panel in the second section of the ceiling. This bit depicts people fleeing to higher ground and Noah’s Ark at the onset of God’s punitive flood.

The Sistine Chapel. Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images.

The woman in question wears only a blue head scarf, signifying she’s married. She clutches just below her right breast, which exhibits several telltale signs of breast cancer, as the experts noted. He areola is not visible, and her nipple is puckered, in a manner her other one isn’t. Two lumps also emerge. One is visible on the right side of the breast in question, just above an area of orange-hued discoloration that appears to be “an artistic effect rather than a typical peau d′orange,” the study stated. The other is visible just before her armpit, indicating she may have swollen lymph nodes, another common side effect.

How exactly did this team locate such minute anomalies amongst all of art history, let alone the Sistine Chapel’s 300 figures? Nerlich said they’ve painstakingly analyzed numerous masterpieces for undocumented evidence of illness. “Since we know that several artists were interested in human anatomy—such as Michelangelo—his work is of particular interest,” he added.

Detail from “The Flood.” Image: Dr. Andreas G. Nerlich.

In their study, Nerlich’s crew posited that Michelangelo painted this particular condition not on accident, but to serve a symbolic purpose. They noted other women throughout the Sistine Chapel, old and young alike, all bear healthy breasts. Furthermore, this woman’s right finger points toward the ground, perhaps signifying an awareness of her fate.

Some might contend that this figure is too young to have breast cancer, since 85 percent of cases today occur in women over 50. To that, this study countered that “applying modern data to the Renaissance period is not entirely accurate.”

The subject of Michelangelo’s later sculpture Night (1524–34) was diagnosed with breast cancer decades ago—and prescribed a message about death’s inevitability. The finding contradicts the traditional interpretation of breasts as feminine symbols of nurturing and proves that, like most of his cohorts, Michelangelo was in fact aware of cancer. By comparison, Nerlich’s team believes Michelangelo aimed to portray the woman in “The Flood” as suffering punishment. Based on some of the other archetypal figures nearby, she may even embody the deadly sin of Lust.

Now that they’ve published their results, this team will continue scouring art history for more opportunities to practice iconodiagnosis.