Sitting in a room with two 20-somethings last month in London, I realized that radical performance art is still very much alive. We were at Albion Jeune, a new gallery in Fitzrovia, in London, founded by the 26-year-old Lucca Hue-Williams, who grew up around performance artists like Vito Acconci and has studied animal works by artists in China, many of them in underground performance. Her opening exhibition last October, I Want to Believe, featuring Danish artist Esben Weile Kjær included a dance macabre, influenced by Weile’s experience with subcultures in Copenhagen. Recently, she tapped Miles Greenberg, the rising star protégée of Marina Abramović, who is also 26, to show his day-long walking performance Oysterknife (2020) at the gallery. It was part of the dual exhibition called “Twenty Four Twenty Four,” which can be seen at all hours until July 28 through the gallery vitrine, that includes Douglas Gordon’s 24 Hour Psycho (1993), a slowed-down version of the classic Hitchcock film.

After walking through the black box space of these two works, which play across from each other, and feature repetitive gestures as asynchronous movements, the image of a female artist contorting her face and body against glass came to me; Greenberg immediately recognized it as Ana Mendieta’s 1972 Untitled (Glass on Body Imprints—face), even though the work is almost as old as he is. “I feel like almost everything I do is in homage to Ana Mendieta. She was such a North Star in the way she commandeered nature,” he said.

Greenberg has been creating performances for over a decade at the roving Marina Abramović Insitute, the Yokohama Triennial, the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin, the Louvre in Paris, and the New Museum in New York, among others. For this year’s Venice Biennale, his eight-hour performance Sebastian, curated by Klaus Biesenbach and Lisa Botti, went viral on social media.

Installation view of “Twenty Four Twenty Four,” Albion Jeune, London, 2024. Miles Greenberg, Oysterknife (2020), 24h livestream, Courtesy of MAI and Phi Centre. Image courtesy the Artist and Albion Jeune. Photo by Ben Westoby

A nod to stolen ebony-colored blackamoors, he silver-painted and punctured his torso with a handful of arrows. It felt like an act of sacrifice. Sugar wax dripping from the ceiling sheared his skin if he moved. He proudly showed me his scars as evidence. “By the sixth or seventh hour, evening set in and there was a beam of sunlight that came in through the window. My whole body got warm and tingly and I didn’t feel the arrows anymore,” Greenberg recalled.

It is not surprising that Greenberg has already come this far in extending his physical capacities. His mother, Phoebe Greenberg, who raised him singlehandedly, is head of art foundation Phi Centre in Montreal and studied physical theater at École Jacques Lecoq in Paris in the 1980s, which he said helped form “a constellation of aunties” in his movement world. It is well-known that Robert Wilson and Édouard Lock were his mentors.

Yet beneath this trajectory is a narrative of rejections from art schools and a few long difficult years in Paris. “I was 20 and I was really struggling,” the artist said. “My work, which has always been medicinal and centering, became a remedy—I had a lot more control inside it than outside, where dangers were lurking. Building a craft allowed me agency and visibility when I felt unseen.”

Miles Greenberg, Etude pour Sébastien (2023). Le Musée du Louvre, Paris, France. Courtesy of the Artist. Photo by Viðar Logi.

He was awarded a residency at Palais de Tokyo in 2019, becoming the first artist to live inside the museum. “I had the whole basement, which was too large for me to fill, and so I would invite drag queens, singers, and dancers I would meet. I’d give them snacks and space to do their thing,” he said. “I was thinking of a deconstructed opera based on Alphaville by Jean Luc Godard, but a Black version.” The resulting performance, Alphaville Noir, unfolded in three-hour segments called “Dusk,” “Nightfall,” and “Midnight,” was inspired by Haruki Murakami’s After Dark. The piece was foundational for Greenberg in his positioning of Black bodies from the world of queer nightlife that he was part of. It also sedimented a certain relationship to time.

On the note of expanding the sense of time, he recounts an instance in Montreal at a DIY artist space where a musician, Charlotte Loseth aka Sea Oleena, played the same note on an electric guitar for two hours. “It was so punk rock and distorted that it kept me completely still.” This willingness to fully inhabit a sensation or space is prominent in Greenberg’s work. In Oysterknife, time becomes tyrannical.

Portrait by Eva Roefs

“I was a bit of a purist with it,” he admitted. “We screen[ed] it from 4 p.m. to 4 p.m. the next day, because those were the hours of the performance.” In the work, Greenberg is captured in different states, moving forward, backward, stretching on all fours and tapping himself to remain awake on the ever-moving conveyor belt. For an artist very much in control of his image—he edits all his work himself—this work shows him unadorned, sporting a grey shirt and khaki trousers. There’s no body paint or artifice, and the blinding white lenses he wears in all his performances, which create a zombie-like distance, are absent.

Miles Greenberg, Lepidopterophobia, (2020). SkyTV (shot at Battersea Arts Centre, London, UK). Courtesy of the artist and Sky Arts.

While Oysterknife indexes violence—it is a response to the brutal hate crime that killed 25-year-old Ahmaud Arbery while he was running—it is also a pared-down gesture. The title comes from a quote by Zora Neale Hurston: “I do not weep at the world, I’m too busy sharpening my oyster knife.”

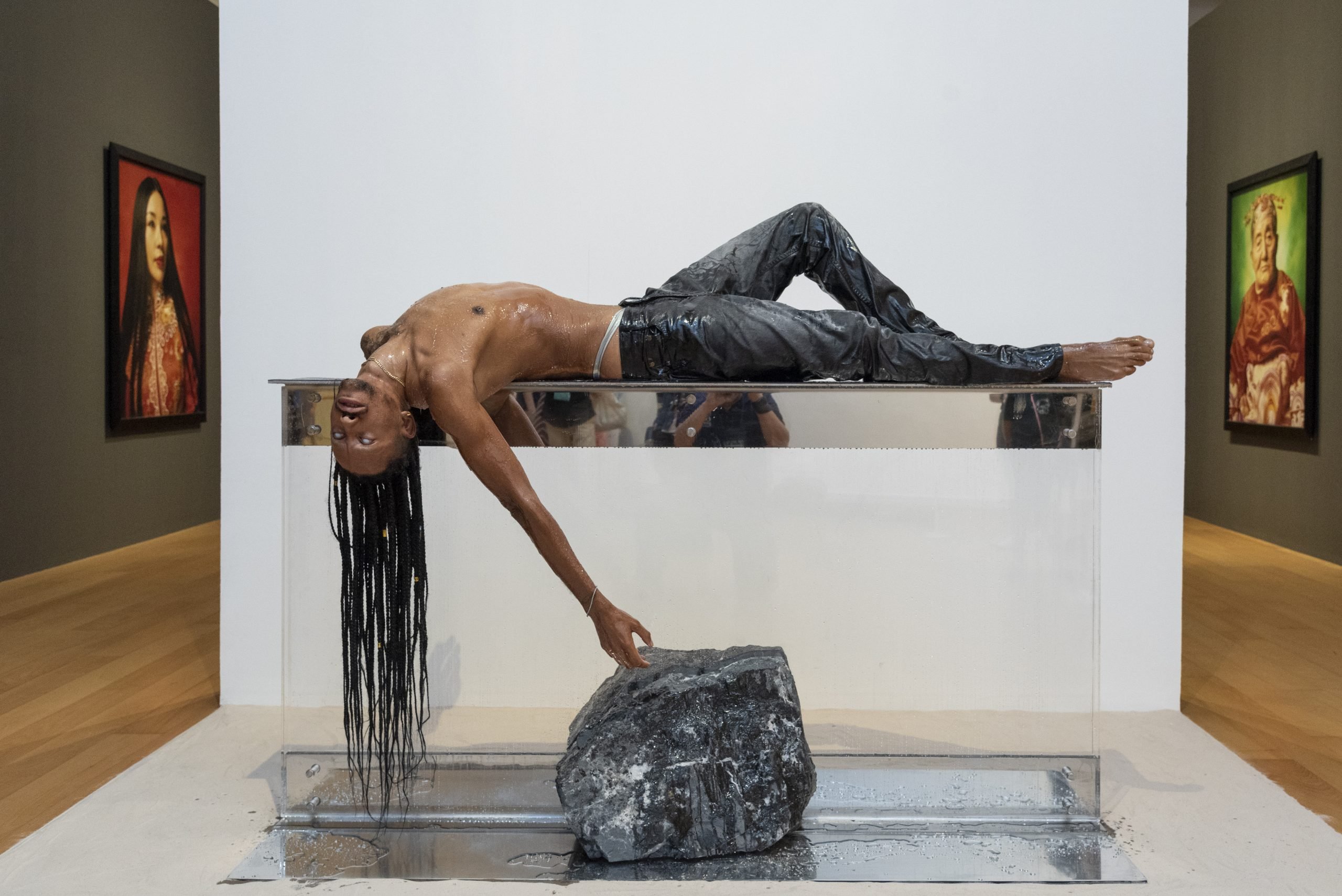

Elsewhere in the gallery is photo evidence of the six-hour performance Late October, another 2020 work. Greenberg’s body, caked in bluish-black, is seen against the backdrop of a massive black orb. There are oiled-black performers, some statuesque on plinths, others around urns on the ground. “Classical sculpture and video games are visceral elements which taught me how to see,” Greenberg told me. “The transition from a live work to an object is something I’ve thought about rigorously. It has to be this slow-burning Battlestar Galactica kind of sequence, something that has the sensuality of an early 2000s sci-fi.” A recent nine-hour performance at the Art Gallery of Ontario, called Respawn, sees him sword-fighting in front of a robotic camera, with nine hyperrealist silicone clones of himself lying down like video game alter-egos that are constantly resurrected.

Despite a level of drama, he isn’t precious about the discourse around his work. “Since I had no educational background in art, if someone wanted to call me Afrofuturist and it got me an exhibition, I went with it,” he said. “My work is ultimately about heartbreak and things that are very universal.”

Miles Greenberg, Late October (2020), Video (color, sound). Still from video © Miles Greenberg, Courtesy of the artist.

His most tender work is The Embrace (2020), which sold to the Faurschou Foundation; it features two semi-nude performers meeting for the first time in a glass cube, clasped in each other’s arms over four days. “Technically this is my longest performance because it’s in an archive,” Greenberg said. “If you sell live art, you aren’t selling the idea or IP but an ongoing, current piece.”

“Duration did not come out of some desire to explore the body in different timescales,” he continued. “I don’t want to fulfill a 45-minute plot-driven expectation. The 24-hour gesture was looking at how the body changing over seven hours is analogous to a stone changing over seven centuries. I’m interested in how statues shape an articulation of the body as an artistic impulse.”

The excruciating stillness required for the sculptural, neoclassical quality of this work magnifies human frailty by mapping it against deep time like, say, the geological lifespan of marble and stone. “In Paris, you can see the statues in the Louvre’s Cour Marly and Cour Puget from Passage de Richelieu at any time. It’s the strongest relationship I have to any art form. There’s a sense of perpetuity and movement that you gain from looking at something every day and thinking about how it changes.”

Miles Greenberg, Sebastian, (2024). Palazzo Malipiero, Venice, Italy. Courtesy of the artist, Museum Berggruen and Neue Nationalgalerie. Photo by Francesco Allegretto.

Greenberg is an artist attuned to minute movements, largely due to his Butoh training at 16, a form of Japanese dance theatre. “The way I think about it is like choreographing your organs, so you aren’t moving from the outside in but from the inside out,” he said. “Over time, I’ve learned to slow down or speed up the muscular waves I can feel in my intestines.” We talk about the kind of fasting that needs to be done in preparation for long performances and little bodily tricks: “Vitamin is consumed better by the tissues of our body after being coated in a layer of fat,” he noted, with a sense of ease and levity that pushes me to dig deeper into pain in durational work.

“In the last two hours of Oysterknife, I’m in euphoria, not pain,” he said. “My work is more about lightness than darkness—because you unburden yourself.”

He noted that this is, not always an easy process. “It’s hard to unburden yourself with things you don’t have language for.” When it’s somatically stored, it’s like an exorcism… You end up using pain, pleasure, sensuality, and whatever is in your body as a gateway to something else. Your brain becomes an organ again and you are inhabiting your body 150 percent.”

Miles Greenberg, Fountain II (2023), Pace Gallery, New York, New York, USA. Courtesy of the artist and Pace Gallery.

At around 7 a.m. in Oysterknife, Greenberg’s body shut down and he passes out for 38 minutes. It was live streamed via the Marina Abramović Institute, [catching the attention of] a security guard who called his mother who then called Marina. “She said, ‘If he’s out for an hour, do something,’” Greenberg said, mimicking her deep accent. “I have a hard time sleeping before 5 a.m. My deepest hours of sleep are from 6 a.m. That’s why I think I fainted.” He explained that these states between waking and dreaming are where most of his ideas stem from.

For artists to put themselves through such feats of endurance requires a different corporeal consciousness. Greenberg articulated [what felt like] an almost unconscious, spiritual understanding of the body. “It’s a secret we cannot talk about here on this couch, something that is close to the divine,” he said. “You can’t come back with it; you have to leave it on the pedestal like a ritual object. So, I put it down and take off the gloves. It doesn’t belong to me.”