At 72, Miriam Cahn is still enraged, a feeling that has always fueled her artwork.

“One can be enraged every day, no? Just look at the news. That’s the daily material that interests me,” she told Artnet News. The Swiss artist spoke as she prepared to receive the Rubens Prize of the city of Siegen, Germany, on June 26; past laureates include the likes of Cy Twombly and Francis Bacon. For the occasion, the Kunstmuseum Siegen is featuring five decades’ worth of the artist’s work in an exhibit titled “Meine Juden” (translated: “My Jews”), on view until October 23.

A feminist and so-called “activist artist” with an eye on political and social conflicts, Cahn touches on hot issues, evoking their ambiguousness and complexity, which often strikes a nerve—perhaps even more so during crisis-ridden times. She has spent decades relentlessly awakening viewers to the horrors that plague our humanity, as well as its fragility.

In her figurative paintings and performative drawings, she depicts sexual violence, war, migrating refugees, and female empowerment, among other subjects. Gender-ambiguous, ghostly bodies appear lost and fleeing on barren landscapes or mothers and children drown in deep, beautiful aqua blues. Lifeless dots for eyes and grins scratched on the canvas conjure deranged smiley faces; elsewhere, bright red genitals are raw and fully exposed.

Miriam Cahn, gefühl beim schlafen 18.2.2022. Courtesy the artist, Meyer Riegger, Berlin/Karlsruhe and Jocelyn Wolff Gallery, Paris, Photo: Heinz Pelz

The works are never easy to take in, which is perhaps why she has only relatively recently been given wider recognition, including at the Venice Biennale this year, where she has a large installation on view within Cecilia Alemani’s group show “The Milk of Dreams.” Her work also appeared in Documenta 14 in 2017 and is in the collections of Tate Modern, London, the Museo Reina Sofia, and the Pinault Collection in Paris, among others.

Yet, despite having become one of Europe’s most important artists, many outside the continent are only just beginning to discover her powerful canvases. There are “people who at first say they can’t look at the work—it’s too violent—and 10 years later, those same people come back, and feel that she is a remarkable artist. But there is a journey,” said Sandrine Djerouet, director and partner at Galerie Jocelyn Wolff which represents the artist alongside Meyer Riegger in Berlin. That said, “for others, it is immediate, and they say: this is life.”

Miriam Cahn, das schöne blau 2021 + 10.1.2022. Courtesy the artist, Meyer Riegger, Berlin/Karlsruhe and Jocelyn Wolff Gallery, Paris, Photo: Heinz Pelz

Developing a Work Method

Throughout her career, Cahn has maintained an unapologetic approach. And while it appears that Cahn has suddenly become well-known, she actually has a long history of key exhibitions, including early presence in European institutions and involvement with a community of feminist performing artists of the 1970s such as Valie Export and Marina Abramovic. Cahn, who lives and works in the Swiss mountain village Stampa, participated in the Venice Biennale back in 1984 and was invited to Documenta 7 in 1982.

Her early protest drawings, like My being a woman is my public art, a work done in charcoal on public construction sites in Basel in 1979 and 1980, are a testament to her longstanding practice of using the public forum to push social issues. The seminal piece refers to the difficulty of looking at her paintings, some of which show nude bodies in explicit, rough sexual contact. Her 2019 retrospective at Kunstmuseum Bern reportedly warned visitors, “This exhibition could hurt your feelings.” Cahn brushes it aside. “It’s not my problem if people have trouble looking at an erect penis. It’s society’s problem, and that’s why it’s interesting,” she told Artnet News.

The artist’s fast working pace (her works are dated to the day they are made) is also something she developed early on and kept, even as she transitioned from mostly large-scale, black charcoal drawings done on the ground, using her entire body, to the colorful oil paintings that she is known for today. Speed “is very important, because it comes from the performance art scene of the 1970s and 80s,” said Cahn. “The body dictated more or less the speed or the duration of a performance [in those works] and I found that very interesting.”

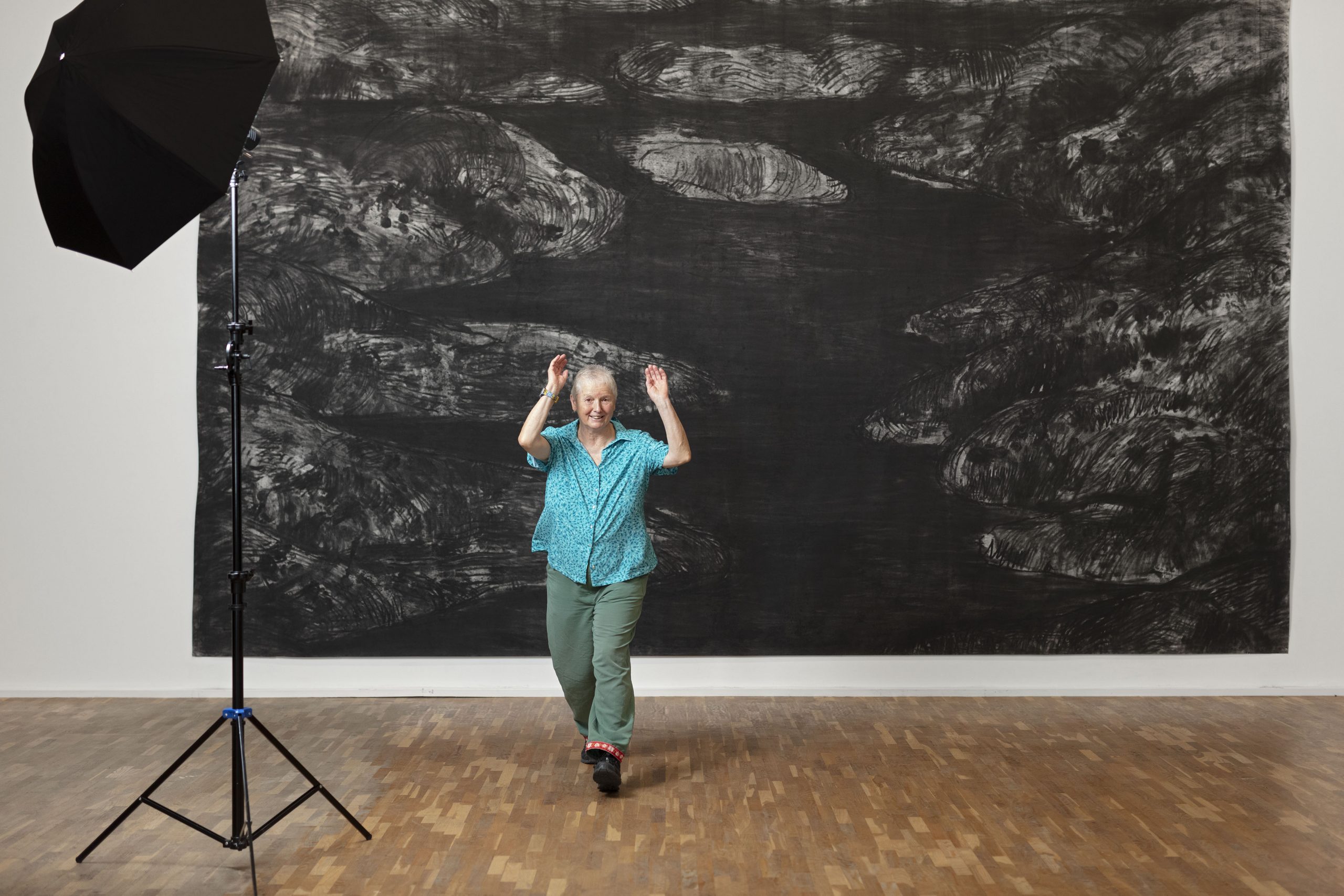

Museum für Gegenwartskunst MGKSiegen Exhibition of the Rubens Prize 2022. Miriam Cahn “Meine Juden.” Courtesy the artist, Jocelyn Wolff Gallery, Paris, and Meyer Riegger, Berlin/Karlsruhe, Photo: Philipp Ottendörfer

She discovered her instinctive method early on when she gave herself five years to test whether or not she was cut out to be an artist. “To make art, you need to be able to structure your daily workload,” said Cahn. “And nobody tells you what to do.” She wanted to make sure she had the drive and direction for that lifestyle. If not, she said she had planned to become a designer.

In the end she found her work rhythm quickly, which is one she said is short and “very intensive.” As for young artists trying to make it in a more difficult economic climate, Cahn suggested trying “to carve out one or two years where you don’t have to run after money, if you can.”

“Art is something that’s slow in itself, so you need enough time to find what you want to do, and how you want to work,” she added.

Miriam Cahn, o.t. 15.11.2021. Courtesy the artist, Meyer Riegger, Berlin/Karlsruhe and Jocelyn Wolff Gallery, Paris, Photo: Heinz Pelz.

What Took the Art World So Long?

Perhaps many were not quite ready for Cahn until more recently. Movements like #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, but also the migrant crisis and the war in Ukraine have contributed to a broader sensitivity for subjects that Cahn has long discussed. She will have a major solo show at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris in February next year.

“It appears as though [her recognition] has come suddenly, but it happened because there was work leading up to it,” said Djerouet. The director confirmed prices for Cahn’s work have increased, with medium-sized works now costing from $50,000 to $105,000, or over $1 million for larger installations, which occur as clusters of paintings not unlike what she is exhibiting at the Venice Biennale. Meanwhile, Djerouet said Cahn’s pieces have started appearing slightly more frequently at auction this year, with prices a little higher than the primary market.

Yet the activism flowing through her paintings bucks recent waves of politically correctness or cancel culture. “BLM is great, but the moment we say that a white artist—a distinction that I already find stupid—cannot work on problems that directly concern Black people, then it becomes wrong. And the same goes for #MeToo,” she said, adding that such progressive movements in themselves are “very good,” but should not be overly simplified. In art, “we have our imaginations. It doesn’t mean it’s realism, though it might be reality,” she said.

Miriam Cahn, schnell weg! 27. + 30.1.2021. Courtesy the artist, Meyer Riegger, Berlin/Karlsruhe and Jocelyn Wolff Gallery, Paris, Photo: Heinz Pelz

“I react as a Jew,” said Cahn, but “only when there is something rather anti-Semitic that happens.” The current exhibition at Kunstmuseum Siegen addresses a sense of otherness and the act of fleeing, which Cahn associates with her Jewish identity; it also addresses anti-Semitism, a topic she has been outspoken about. The exhibition’s title, called “My Jews,” is a continuation of her publicized critical response late last year to the Kunsthaus Zürich’s new wing dedicated to the art collection of Nazi-arms supplier, Emil Georg Bührle, despite questions around the provenance of some of the works, possibly acquired from Nazi victims.

Though she rebuked cancel culture in general, she did ultimately try to withdraw from the collection of the Kunsthaus Zürich after a representative from the museum concluded that Jews in Switzerland were not oppressed during World War 2 during a conference. The artist was angered by what she called a “false” statement and a case of “historical blindness.” She offered to buy back her roughly 30 paintings. “I started to react violently, because it was too much,” she said. The institution refused, but her proposal “was a bomb that caused a lot of reactions,” she noted.

Indeed, Cahn feels it is her “duty” to conjure the hardships of others in her signature, empathetic way. “It might be my Jewish side to tell myself that, if you have a privilege [such as freely making artwork in the Swiss Alps] then it’s your duty to comment” on the pain of others. And also, she said, “to think: it could be me.”

Miriam Cahn’s exhibition “My Jews” is on view until October 23 at Museum für Gegenwartskunst Siegen.