October 18, 1961, might just be one of the most embarrassing days in the history of museums.

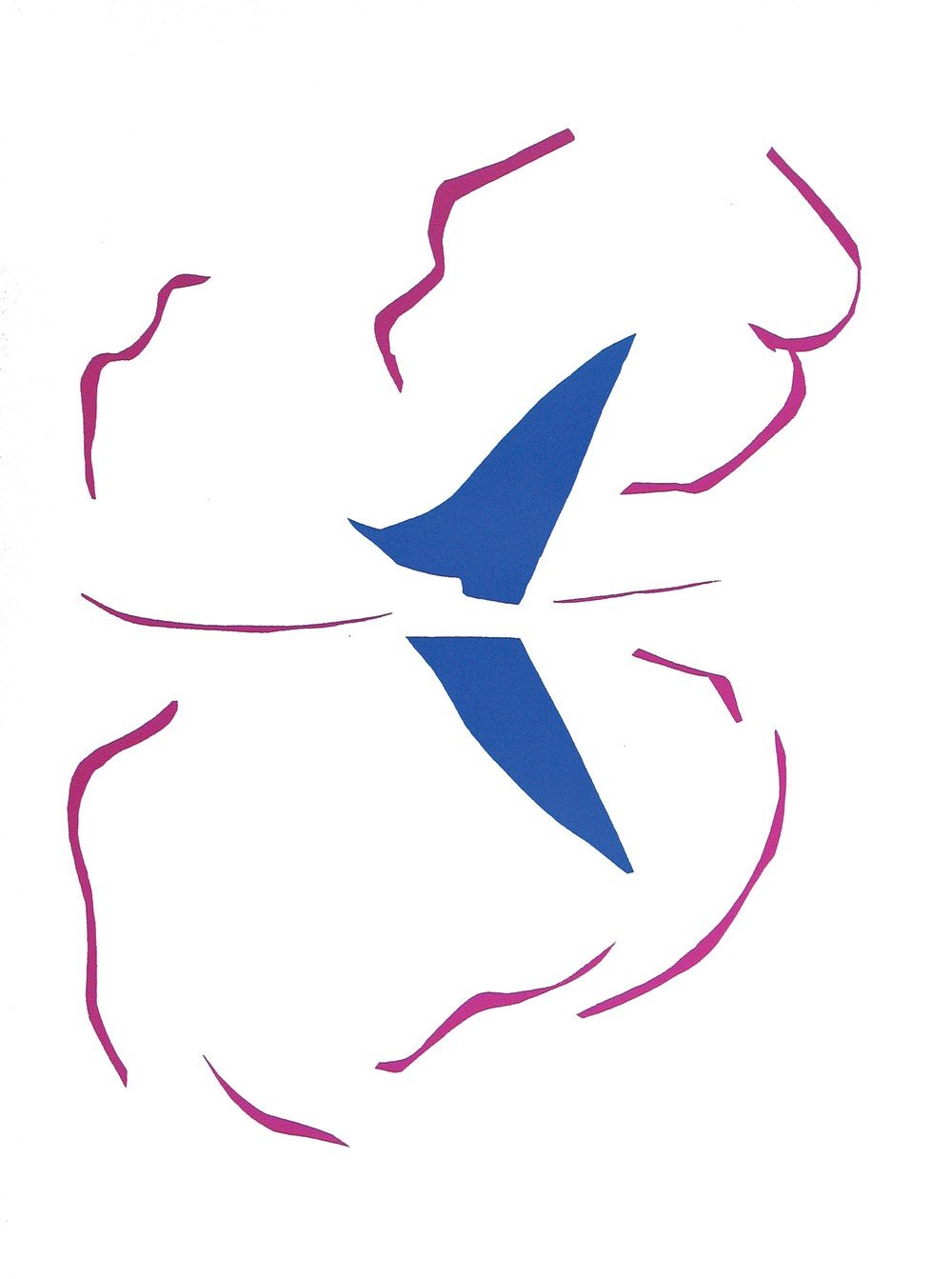

On that fateful morning, New York’s Museum of Modern Art opened the doors to a new exhibition, “The Last Works of Matisse: Large Cut Gouaches,” unaware that one of the works, Henri Matisse’s Le Bateau, was hanging upside down.

The error wasn’t discovered for 47 days, going unnoticed by curators and museum staff, as well as some 116,000 visitors; among them was Matisse’s son Pierre, who was an art dealer. The mistake was somewhat understandable, given the nature of the gouache work, a simple paper cut-out work of a sailboat and its reflection, expertly created by the artist with just a few simple shapes.

Sharp-eyed Genevieve Habert, a Wall Street stockbroker, was more observant. After three visits to the show, she became convinced that the painting had been flipped, telling the New York Times that she was certain Matisse ”would never put the main, more complex motif on the bottom and the lesser motif on top.”

“The Last Works of Matisse: Large Cut Gouaches” at the Museum of Modern Art in 1961. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York.

Habert purchased the exhibition catalogue and did a side-by-side comparison, proving her hunch. The museum guard she alerted to the matter was not exactly receptive, however, saying “you don’t know what’s up and you don’t know what’s down and neither do we. We can’t be responsible for the printers.”

Undeterred, Habert contacted the Times, who revealed the unfortunate error in a December 5 story, one day after the director of exhibitions, Monroe Wheeler, finally flipped the painting right side up. He told the paper that “it was just carelessness.”

The New York Times article about how Henri Matisse’s Le Bateau (1953) was hung upside down.

The assistant curator responsible for the installation, Alicia Legg, called the artwork “very confusing,” pointing to the upside label on the painting’s reverse side, and deep existing screw holes suggesting that it had been hung incorrectly before. (There were also fainter, less noticeable holes on the correct side.) Unfortunately, the show closed December 4, meaning that Le Bateau was only displayed correctly while the exhibition was being deinstalled.

A similar incident took place at the new Whitney Museum of American Art in 2015. A Jackson Pollock drip canvas, Number 27, 1950, shown horizontally in the artist’s catalogue raisonée and the museum’s collection handbook, was flipped vertically for the institution’s inaugural exhibition, “America is Hard to See.”

The Whitney’s decision, however, was intentional, based on photographs of the painting installed that way the same year it was made, at New York’s Betty Parsons Gallery.