(© 2016 Estate of Marcel Broodthaers / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SABAM, Brussels)

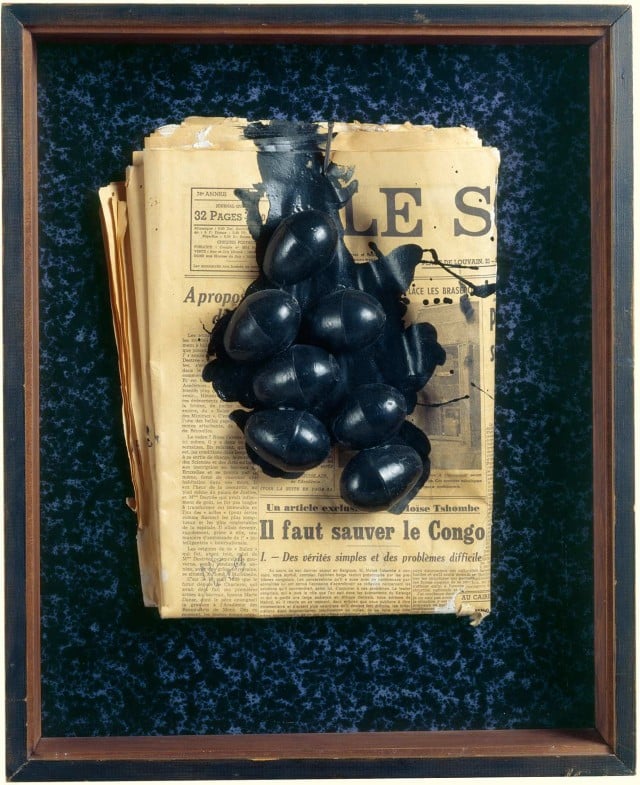

THE DAILY PIC (#1488): This is Le Problème noir en Belgique (“the black problem in Belgium”), by the great Belgian artist Marcel Broodthaers, and it is a key piece in the impressive survey of his work that’s opening Sunday at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. (It also happens to be one of MoMA’s most notable recent acquisitions.) Broodthaers worked out his Problème in 1963 and ’64, when he was just in the process of switching from decades of writing poetry to a dozen years making visual art. He died in 1976, of liver disease, on his 52nd birthday.

When I first contemplated this piece and its mates in the MoMA show, I thought the trick to understanding Broodthaers, one of the most chewy of all modern artists, was to recognize the humor in his work. He goes for such an absurd accumulation and concatenation of stuff and symbols and meanings – a newspaper paired with bizarre fake eggs – that you feel like you’re in the hands of some gleeful artist-clown. One of the oldest tricks for dealing with truly, vitally baffling art has always been to bill it as funny, and I’ve gone that way any number of times. It means you don’t have to look quite as deeply for sense in the art, and it also allays any fears you may have that either you are dumb, or it is. It’s all just a joke, and you get it – which puts you one-up on the sober dullards who don’t.

But thinking more deeply about today’s Pic, and the rest of the MoMA show, I started to feel that terror and horror and sadness were Broodthaers’s true driving forces. After all Le Problème noir uses as its background a newspaper in which a writer from the Congo speaks of the chaos left behind by Belgium’s colonial adventures in his native land. Broodthaers then covers his newspaper in eggs, normally white and a symbol of generation but here made to ooze with midnight-black paint. The whole package calls to mind those horrendous images that circulated in the early 1900s, showing Congolese people with their limbs hacked off by Belgian overseers. And Le Problème noir is a piece, let’s not forget, that helps launch Broodthaers’s entire career in fine art, so it makes sense to read it as unlocking his larger project.

Around the time he was digging into his Problème, Broodthaers was writing an article about American Pop Art, and his reading of it is almost entirely dark: He celebrates the movement for continuing along the “hellish path” set by Dada after World War I and talks about how Pop “defies harmony and good taste” while “screaming out curses and calling down contempt and profanity on its own head.”

There’s no way Broodthaers didn’t recognize the comedy and silliness in the art of the Pop-sters. He just chose to see it as camouflage for despair.

Broodthaers deployed the same camouflage.

For a full survey of past Daily Pics visit blakegopnik.com/archive.