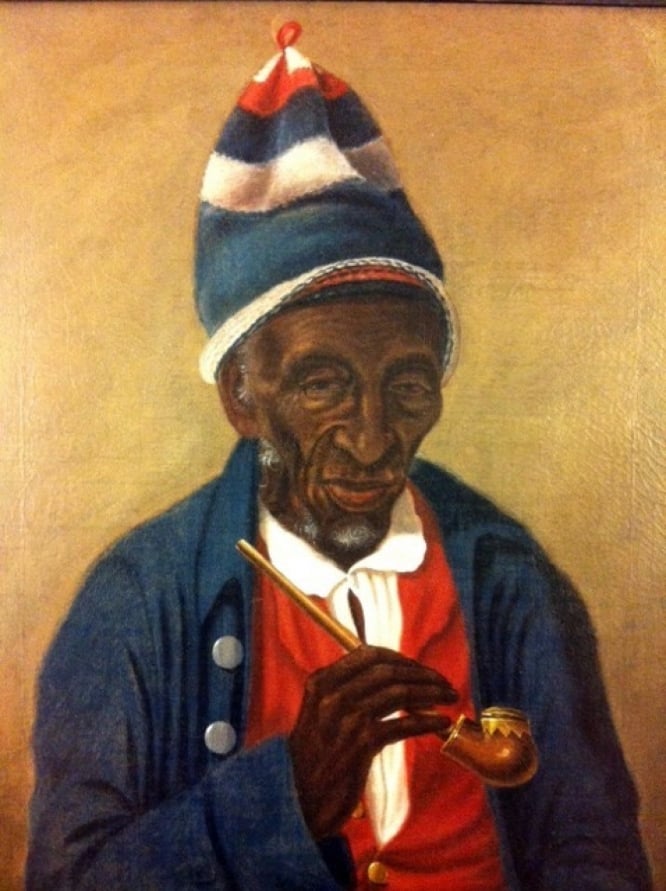

The National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC, has added a portrait of Yarrow Mamout (ca. 1736–1823) to its display of “American Origins,” an exhibition meant to tell the story of the country. Who is he, and why is he significant?

Mamout was born in Guinea in West Africa; was brought to the United States in bondage at the age of 14; lived to be freed at the age of 60, in 1796; and died in relative prosperity as a member of Georgetown’s small community of free blacks. He also happens to have been a practicing Muslim, and the portrait depicts him in a kufi, a hat worn by African Muslim men.

To give a sense of the figure he cut in his day, Mamout’s obituary in the Gettysburg Compiler read, in full:

Died—at Georgetown, on the 19th ultimo, negro Yarrow, aged (according to his account) 136 years. He was interred in the corner of his garden, the spot where he usually resorted to pray… it is known to all that knew him, that he was industrious, honest, and moral—in the early part of his life he met with several losses by loaning money, which he never got, but he persevered in industry and economy, and accumulated some Bank stock and a house and lot, on which he lived comfortably in his old age—Yarrow was never known to eat of swine, nor drink ardent spirits.

Formal portraits of African Americans were rare in the early 19th century, but Mamout sat for two. Charles Willson Peale, one of the most celebrated painters of the period, created a portrait which today is a highlight of the Philadelphia Museum of Art collection. The one on view at the NPG (on loan from the Georgetown Branch of the DC Public Library) is a more folky canvas by the relatively obscure James Alexander Simpson.

Charles Willson Peale, Portrait of Yarrow Mamout (Muhammad Yaro). Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

It is worth noting how recent the renewed interest in Mamout is. Just 10 years ago, in a long essay called for the Washington Post “The Man in the Knit Cap,” James H. Johnson wrote of being captivated by the Simpson portrait—but having to “sift through government records, manuscripts, books, and newspapers, and take oral histories to reconstruct his life and legacy in detail.” Johnson went on to write From Slave Ship to Harvard: Yarrow Mamout and the History of an African, published in 2012 by Fordham University Press.

The inclusion of the portrait at the NPG is a step towards presenting a more complex idea of what the exhibition title, “American Origins,” means. The ongoing installation is described as a “conversation about America,” and comes at a time of particularly poisonous anti-Islamic rhetoric, so it can’t help but make a point.

“His portrait reminds us that Muslims have been a part of the fabric of this nation since the beginning,” NPG director Kim Sajet said in a statement about the inclusion.