The name Nero, like Madonna or Voltaire, needs little introduction. Even if you didn’t know that the Roman emperor’s full name was Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, or that he succeeded the throne at the tender age of 16 (only to die by 30), one of the best-known sayings about Nero is that he “fiddled while Rome burned.”

The callous personality that the phrase conjures is in keeping with the broader historical narrative of “one of Rome’s most infamous rulers, notorious for his cruelty, debauchery, and madness,” according to the press release for the British Museum’s new exhibition dedicated to Nero.

A few of the notable deeds associated with Nero include executing his mother and at least one wife (though likely two), competing publicly in chariot races, acting on stage, and having his likeness reproduced in statues around Rome—thought to be evidence of his megalomania—and, of course, starting the Great Fire of Rome and “fiddling” as it raged.

“The Nero of our common imagination is an entirely artificial figure, carefully crafted 2000 years ago,” curator Thorsten Opper, who specializes in ancient Rome at the British Museum, said in a statement. He added that the exhibition, which includes more than 200 objects, “reveals a society that was prosperous and dynamic, yet full of inner tensions, which erupted in a violent civil war after Nero’s death.”

So, how did the Nero of history morph into the caricature of evil taught in schools today?

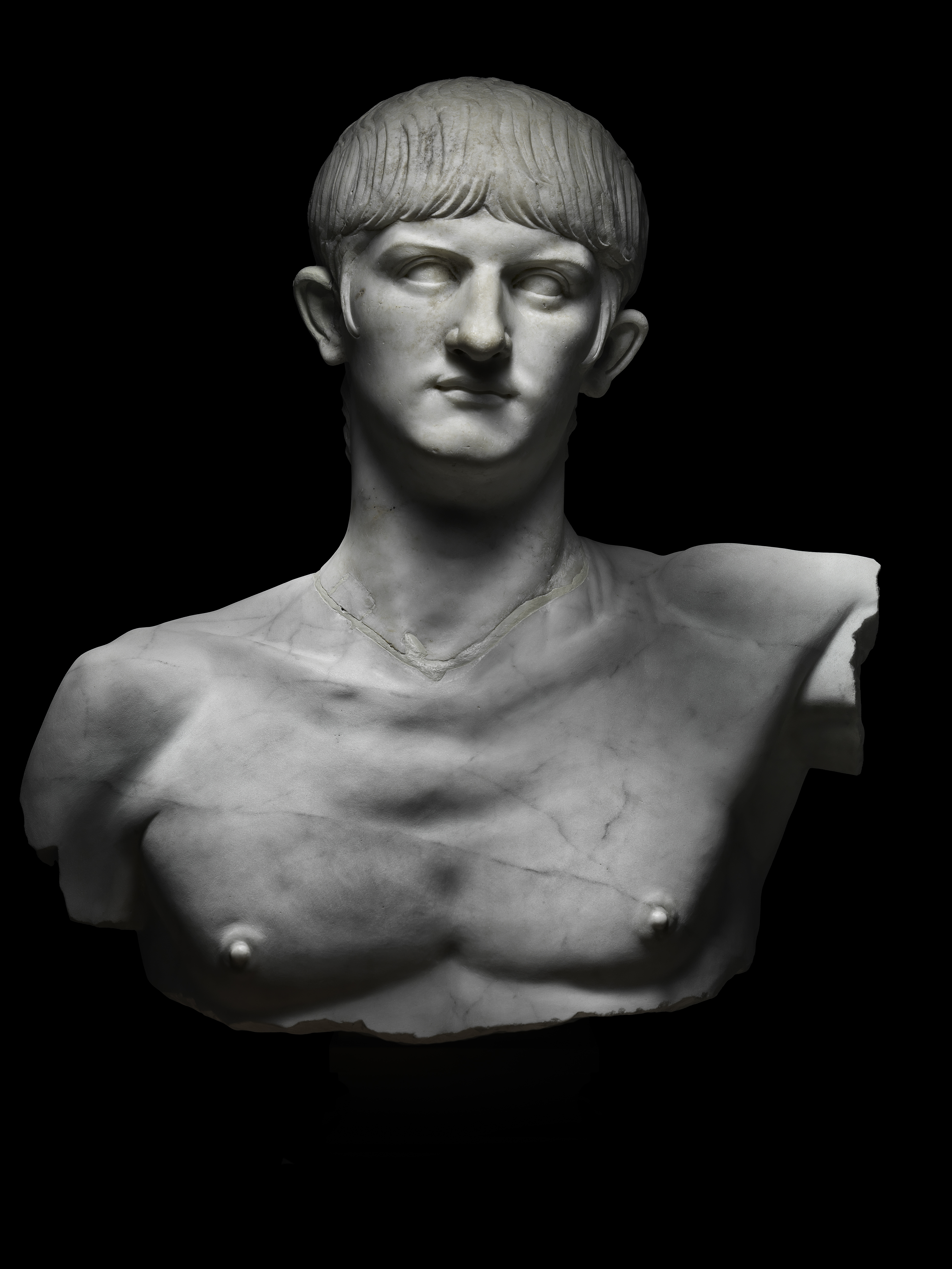

A marble head of Nero (AD 50Ð100), on loan from the Musei Capitolini in Rome. Photo by Andrew Matthews/PA Images via Getty Images.

“Our aim is not to reveal a ‘good’ Nero behind the clichéd ‘monster’, but to show that there were very different perceptions and narratives,” project curator Francesca Bologna told Artnet News in an email. “We do so by looking critically at ancient sources and using archaeological evidence.”

Through historical documents and artifacts, the record shows that “Nero’s actions enjoyed broad popular support, but were rejected by parts of the elite. His memory was contested, but in the end one particular, very hostile elite view won out.”

Some of the objects on display in the exhibition are examples of anti-Nero propaganda, like the famous marble head depicting the emperor with hollow eyes and a blunt haircut. As happened with many busts of the maligned emperor, the top half of the sculpture was re-shaped after his death from the idealized likeness to what Opper once described in an interview as “a stereotype, an artificial image” that differs from those created during his rule.

Other research, such as excavations of the Palatine in Rome, offer “a radical reassessment of the historical sources,” Bologna said. “With this comes an urgent need to challenge traditional preconceptions and explore what the ancient elite narrative on Nero tells us about the inner conflicts of Roman society.”

See more objects from the show, below. “Nero: The Man Behind the Myth” is on view at the British Museum through October 24, 2021.

The Fenwick Hoard, England, AD 60–61. © Colchester Museums.

Head from a copper statue of the emperor Nero. Found in England, AD 54–

61. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Miniature bronze bust of Caligula, AD 37–41. © Colchester Museums.