If you could replicate the experience of visiting a gallery through your phone, would that be good or bad news for art and the art business?

We may be about to find out thanks to Artland, an app and social networking platform founded in 2016 by Copenhagen-based brothers Jeppe and Mattis Curth. The fast-growing company wants to become the Zillow for art—a place where collectors and dealers can come together online to view, share, buy, and sell.

The company was founded with a goal that many young companies have today: to, as co-founder Mattis Curth puts it, “lower the barriers to enter the art market.”

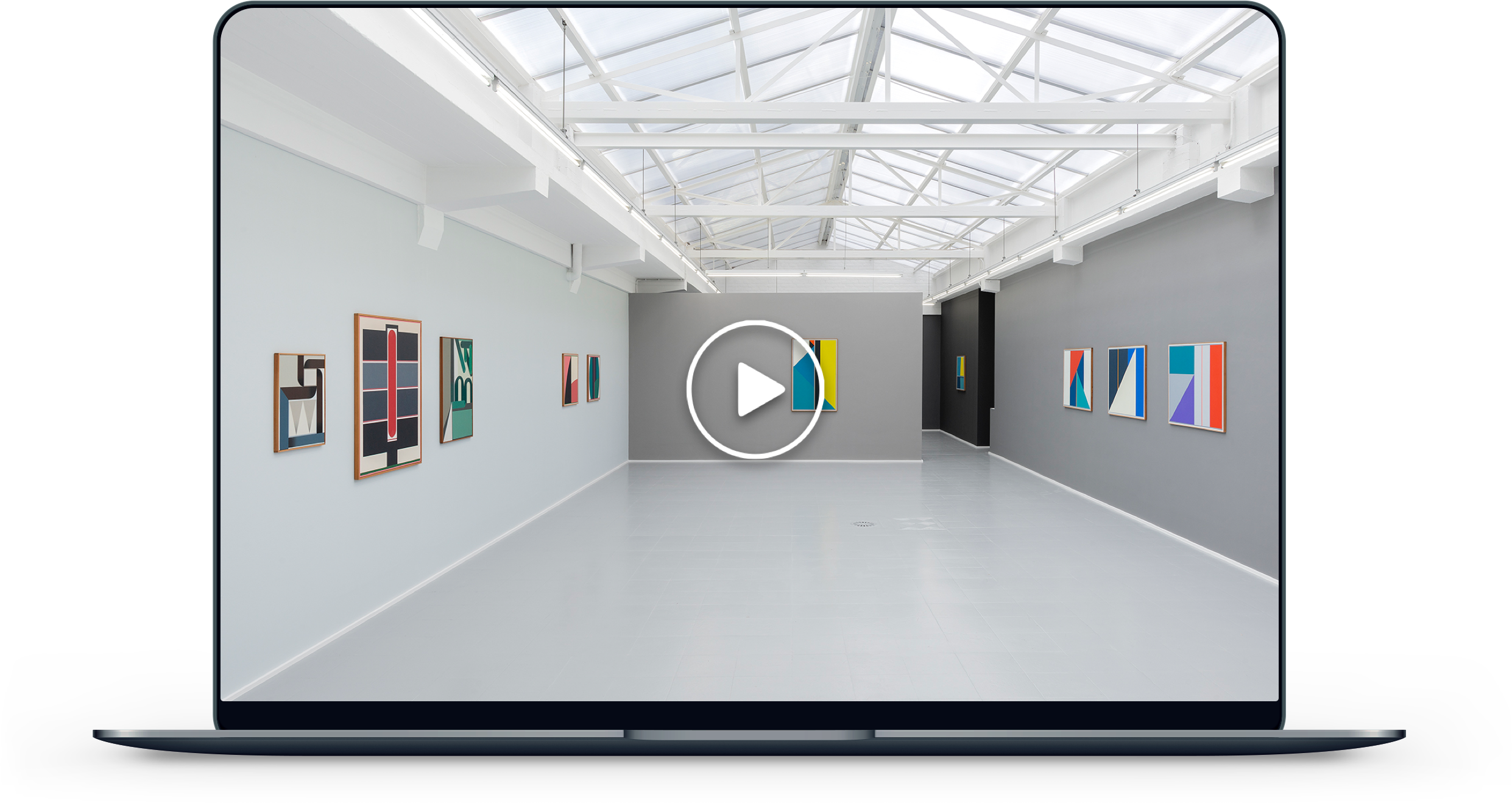

To be sure, Artland isn’t the first startup to attempt to demystify the art-viewing and art-buying process (it isn’t even the second, or the third). But the company has grown quickly and quietly thanks in part to its focus on the visual: it creates interactive, 3-D scans of exhibitions in galleries, museums, and art fairs around the world, allowing users to explore, say, the brushstrokes of a painting at a gallery in Berlin, or the wall label on a sculpture at an art fair in New York—all from the comfort of their phones.

Mattis Curth and his brother Jeppe hatched the idea while finishing up their studies at Aalborg University in northern Denmark. After finals, the duo relocated to Copenhagen, recruited a web developer, and went to work. They started with seed money from friends and family, and later raised $1 million in their first official round of funding from such eclectic sources as professional handball player Mikkel Hansen; Olympic dressage champion Andreas Helgstrand; and musician and songwriter Shaka Loveless. Within months, the app was live.

Pages across the Artland app platform. Courtesy of Artland.

Neither of the Curths had a background in art. But, for them, that was the point.

“We had fallen in love with some pieces of art and with some exhibitions, but it was so difficult for us to really understand it,” Mattis explains. “The whole goal was to help people like ourselves—emerging, millennial collectors—to start buying art, to experience living with art.”

Artland is free for individual users, who can create a profile, browse art from around the world, save favorite works, then slide into the DMs of other individual owners or galleries to arrange to purchase a piece that is for sale.

Galleries, on the other hand, are required to pay a monthly subscription (about €200 or $227, as of now) to post their wares and 3-D scans of their exhibitions. (Artland has trained technicians in major cities around the world who will schedule appointments with galleries to scan the show with a special 3-D camera.)

The app currently boasts around 50,000 users, according to the brothers. And it’s catching on especially quickly with dealers. Artland launched the 3-D component of its software five months ago; since then, more than 140 galleries across Europe, North America, and Australia—including Cardi Gallery of Milan and Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects of New York—have already signed up. “We were very surprised by the way that galleries have adapted to it, to be honest,” Mattis says.

Indeed, one would not necessarily expect galleries, who so often decry the decline of foot traffic to their brick-and-mortar locations, to embrace technology that could make people less likely to visit them in person. Why support a company that aims to be so successful at replicating your work digitally as to render you almost useless?

“That’s a question that we hear a lot,” Mattis says. “But a lot of studies show that if you give people a very good experience online, they are more likely to visit in person. We actually believe we can create more visitors with this tool.”

Mattis and Jeppe Curth, co-founders of Artland. Photo: Mikkel Hjort-Pedersen.

The app also offers a number of supplementary tools, including digital archiving for galleries. “It takes weeks and months to put together an exhibition,” Jeppe says, “and after the short run is done, the only thing you have left is images of it. The 3-D function is not only a marketing tool when galleries open an exhibition, it can be used for archiving too, allowing shows to live online even after they’re taken down. And not every exhibition sells out, so this tool makes it possible for people to visit after the fact and purchase later on.”

Looking ahead, the company, which now has over 15 employees, plans to bring the technology into artists’ studios, allowing collectors to see 3-D views of artworks while they’re being made (assuming, that is, that the artists don’t mind being watched). The brothers also foresee a future in which gallery-goers can put on special glasses to see what future exhibitions will look like, long before they’re installed.

For now, however, they are focusing on expanding their footprint, bringing their technology to more galleries and collectors worldwide.

“We believe that being able to see 3-D exhibitions all around the world is something there’s a huge need for, both for collectors and galleries,” Mattis says. “Our goal is to give you the exhibition you want to see, no matter where you are in the world.”