“Death.” “Dogs.” “Sunsets.” “The Hidden Faces of The Moon.” “The Distorting Lens of the Colonial Machine.”

These are some of the entries you’ll find in Photo No-Nos, a sort of encyclopedia of all the subjects deemed off-limits by more than 200 contemporary photographers, writers, and curators. Among the experts offering their personal “no-nos” are well-known contemporary artists such as Sara Cwynar, Roe Ethridge, and Taryn Simon.

Arranged alphabetically, from “Abandoned Buildings” to “Zoom Screenshots,” the book’s list of subjects are broken up by longer passages from contributors elaborating on a particular subject or theme. For Alec Soth, “Cemeteries” tops the list of banned subjects; for Lyle Ashton Harris, it’s “Landscapes.” Eva O’Leary avoids photographing people from above, especially other women. “This way of seeing caters to the male gaze,” she writes.

Published this month by Aperture, the book could have come off as a tedious screed about the goal posts of “good” and “bad” photography. Instead, it ends up as something much more rewarding: a sometimes amusing, sometimes serious look at the ways in which contemporary photographers are wrestling with the baggage of their own medium.

Photo No-Nos: Meditations on What Not to Photograph (Aperture, 2021). Courtesy of Aperture.

Jason Fulford, a well-known photographer himself who designed and edited the book, said it wasn’t easy to get photographers to articulate their taboos. On first hearing the prompt, many responded the same way: “I don’t like to self-censor.” So Fulford had to find ways to get at the question more indirectly, asking about “the things you used to avoid and don’t now” or “a subject that someone said you shouldn’t photograph that you disagree with.”

The resulting reflections range across subjects from “Street Signs” to “Innocent White Fantasies” to “My Mother’s Wedding Photos Where She Cut My Dad Out of the Picture.” “Some people would take it in a really heavy way and other people would take it in a practical way,” Fulford explained.

(The designer did not include his own list in the book. If he had, he says, it would’ve gone something like this: “Shrubbery,” “Cheerleaders,” “Tarps Over Cars,” “Mannequins.”)

Alec Soth, Ed Panar, Pittsburgh (2019) from

Photo No-Nos: Meditations on What Not to Photograph(Aperture, 2021). © Alec Soth/Magnum Photo.

Fulford put out his asks to fellow photographers in the summer of 2020, and it’s easy to tell. Numerous passages refer to the confined conditions of lockdown; others contemplate the ethics of protest photography amid 2020’s wave of demonstrations.

On the latter point, Stephanie Syjuco says she doesn’t take pictures of people’s faces at protests: “Even if we think a political situation doesn’t implicate someone in a certain way, I don’t have confidence that images won’t be weaponized later,” she writes.

Olu Oguibe, on the other hand, would never alter a protest photograph to hide a marcher’s face: “Does a photographer have the right, never mind the obligation, to obliterate a subject’s identity without that person’s approval?”

These kinds of differences of opinion are everywhere in Photo No-Nos. Over and over again, one image-maker’s cliche is another’s crowning achievement. In the end, Photo No-Nos is more of an invitation to the reader to think about what is valuable for them, rather than a list of tips to follow.

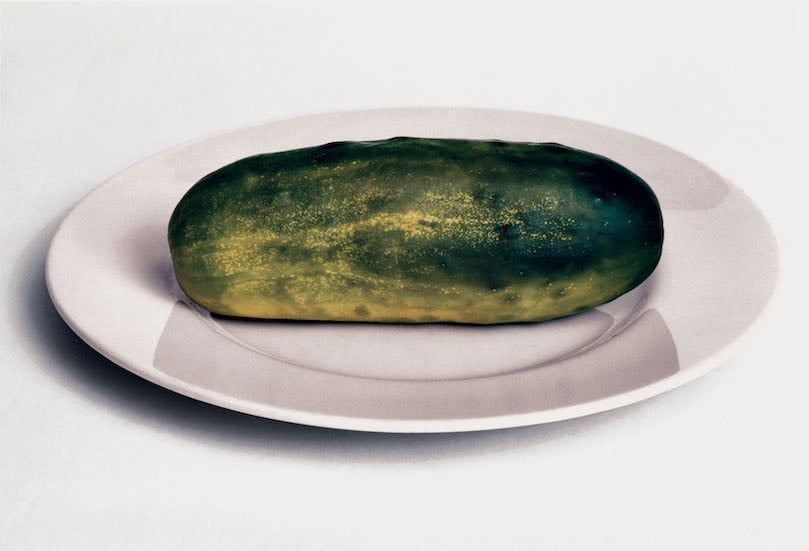

William Wegman, Mondo Bizarro (2015) from

Photo No-Nos: Meditations on What Not to Photograph(Aperture, 2021). © William

Wegman.

Perhaps the entry in the book that best illustrates this comes from Aperture’s own senior editor, Denise Wolff, who worked with Fulford to put it together. She recalls an ill-fated list of “Things That Should Never Be Photographed,” once taped to a high-trafficked wall in the publishing house’s headquarters.

“As photographers flowed through, the list felt too snarky and dismissive,” Wolff writes. “Caveats were added: Things that Should (Almost) Never Be Photographed Anymore and then Unless You Can Do So Really, Really Well and later, or Differently. After a few days, we took it down.”