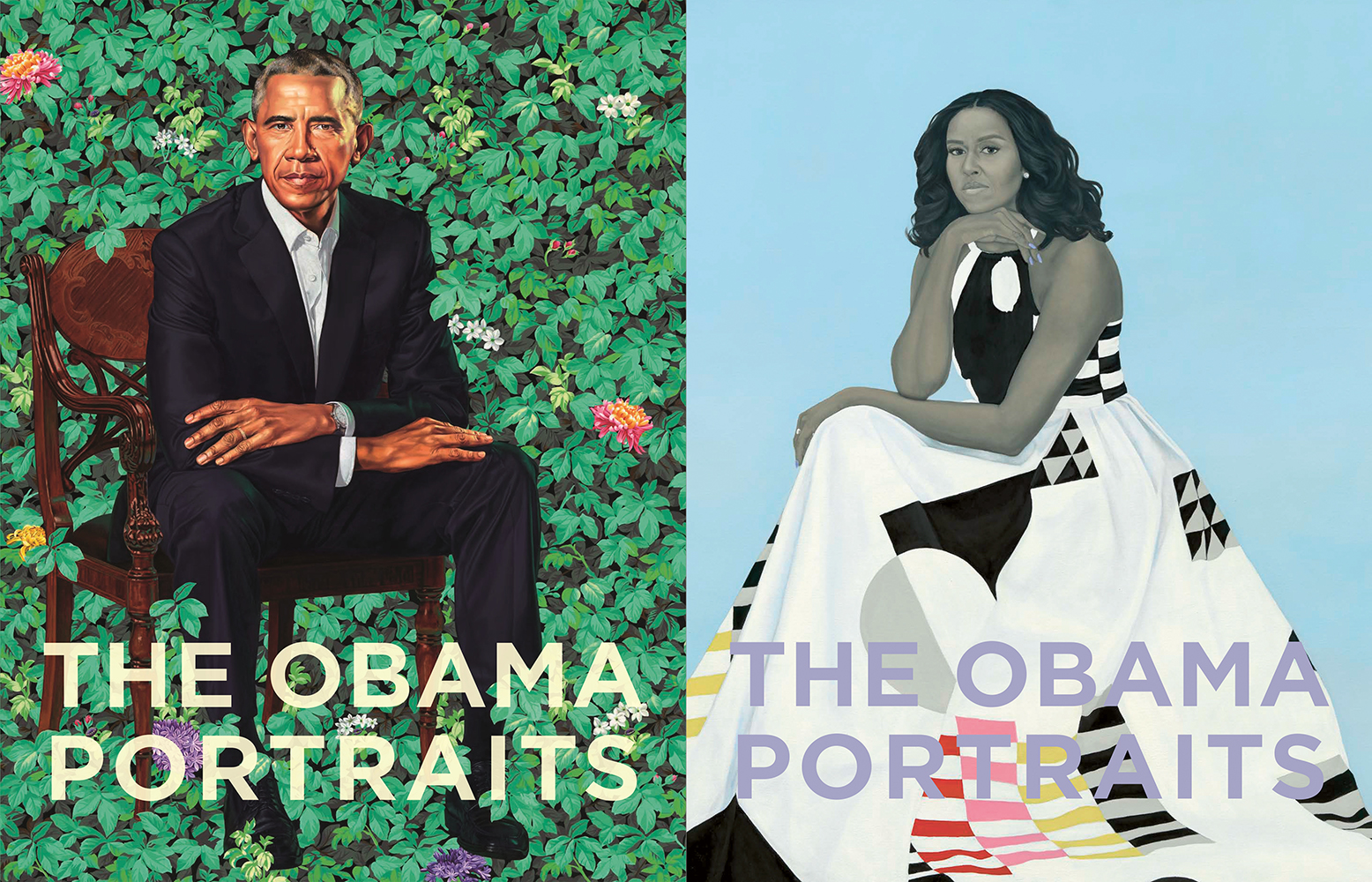

It’s rare for a painting to be the subject of international headlines. But this was the case for the pair of portraits that Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald made of President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama, which made waves around the world.

When the portraits were unveiled at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery (NPG) in February 2018, they were a bona fide cultural phenomenon. The museum’s attendance tripled; its web traffic went through the roof. Lines the length of football fields formed en route to the colorful canvases, snaking through hallways and stairwells out into the museum’s courtyard.

But it wasn’t just the amount of attention surrounding these paintings; it was the tenor of it. Stories of visitors praying or breaking down in tears before the portraits circulated on social media. An image of a two-year-old girl, Parker Curry, went viral after a stranger snapped her looking up in awe at Michelle’s image. (The girl’s mother had to hire a publicist to field all the ensuing interview requests.)

Photo: Paul Morigi. Courtesy of Princeton University Press.

The portraits transcended art and politics, inspiring the kind of spiritual experience typically associated with religious icons. In fact, that’s not far off, says Kim Sajet, the NPG’s director.

“It’s a form of what I call secular pilgrimage,” she tells Artnet. “Much like people go to Graceland or John Lennon’s grave—the response has that quality to it.”

Now, two years after the frenzy, the museum is taking stock of the artworks’ impact with a new book published by Princeton University Press.

The Obama Portraits, out this week, retraces the portraits’ journeys, from behind-the-scenes looks at Wiley and Sherald in their studios, to the much-publicized unveiling, and finally to the burst of popular attention and interest that followed.

Photo © 2018, The Washington Post. Reprinted with permission.

“I think it would be true to say that we were all caught off guard,” says Sajet of the response to the paintings. “We knew they were going to be popular but we had no idea that they were going to be this popular. It was extraordinary. We joke about it now, but it was 24/7 here at the time. We had staff coming in on weekends and in their spare time just to be here to talk to crowds who were lining up. Brochures that we had printed for six months lasted six weeks.”

The director recalls a meeting with the museum’s design team prior to the portraits going on view. They wanted to put up stanchions in front of the canvases to keep viewing experiences orderly.

“I said, ‘Guys, I think you’re being a little overzealous. Do we really have to do that?’”

Ultimately, Sajet sided with the design team, and she was glad she did. Not only did the stanchions lend a sense of organization to the chaos that ensued, they changed the way people interacted with the paintings, giving onlookers the space to share a rare, intimate moment with the works.

Photo: Paul Morigi. Courtesy of Princeton University Press.

Waiting in a long line is never a good time, but an overwhelming sense of fellowship flourished among those waiting to commune with Barack and Michelle.

“I would go up to these people who had been lining up for hours and would say, ‘Wait a minute, don’t you live around the corner? The paintings aren’t going anywhere, you can come back in a couple of months when it won’t be so crazy,’” Sajet recalls. “And they would say, ‘No, that’s the point. We want to be here with everyone else. We love the environment!’”

The experience wasn’t limited to these two portraits, either. The rush of visitors also developed new relationships with the rest of the NPG. Sajet explains that the museum’s “In Memoriam” wall of portraits depicting recently deceased figures grew in popularity too, occasioning the kind of lengthy lines and creative, emotional responses that the Obama portraits inspired. Visitors left purple flowers in front of Prince’s painting, for instance, or wept before Aretha Franklin’s likeness.

President Barack Obama, First Lady Michelle Obama, and their daughter Malia look at Alexander Gardner’s 1865 photograph of Abraham Lincoln during a visit to the National Portrait Gallery in 2014. Courtesy of White House Photo/Alamy.

Now, with its eyes wide open to these new and inspired forms of visitor engagement, the museum is tweaking its broader approach.

“It’s made me think a lot more about creating spaces that are special, where you can sit on a bench and have a moment with another person or by yourself,” says Sajet. “It’s a little old-fashioned, but I think people are looking for that now.”

The Obama Portraits is out now from Princeton University Press. The portraits of President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama will go on their first national tour starting next year.