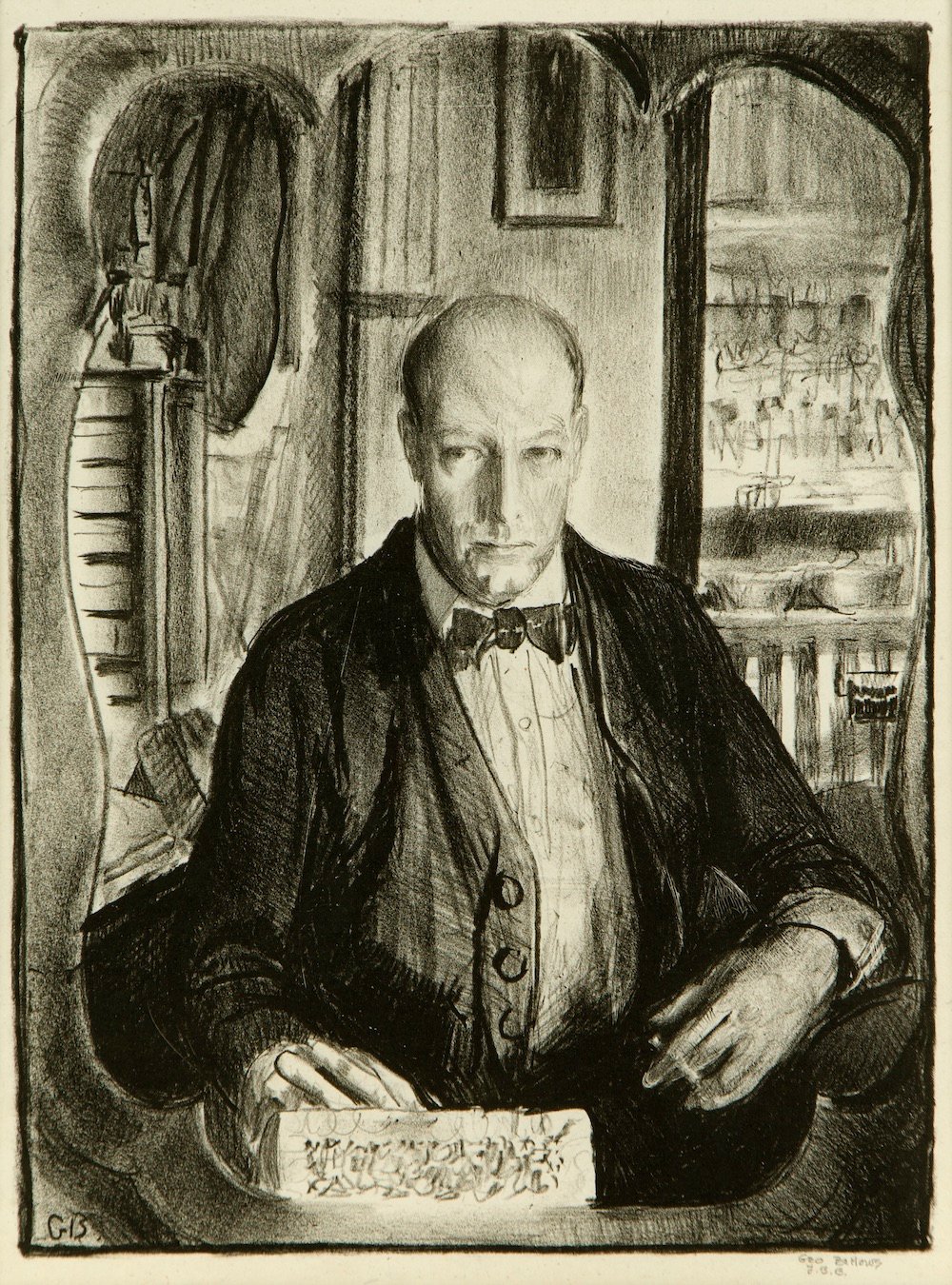

The American Realist George Bellows (1882–1925) was a maker who contained multitudes: an athlete and an artist, a war supporter and a government critic, a socialist activist and a member of elite social circles.

“He was all the contradictions that make up this country,” said Nannette Maciejunes, executive director and CEO of the Columbus Museum of Art (CMA) in Ohio, which owns the 20 paintings and 175 lithographs by the artist—the largest collection of Bellows’s work in the U.S. And yet, she noted, too often are those complexities lost in the modern conversation around the artist, who died at just 42.

Now, the CMA is aiming to fix that. This week, the institution cut the ribbon on a new research center dedicated to Bellows—a destination for academics and fans alike that will offer up intimate views of the artist’s work on request and host dedicated programming around him and his Ashcan School contemporaries throughout the year.

“It’s really a space for scholars and students to be able to dig into documentary files and to look at works of art one on one,” Maciejunes added.

George Bellows, A Stag at Sharkey’s (1917). Courtesy of the Columbus Museum of Art.

The George Bellows Center will also display the artist’s paintings and prints, but exhibition of his work is not the center’s primary purpose, since the artist, a proud native son, is well represented in the museum’s permanent galleries.

He was born in the state capital in and stayed for college at Ohio State until 1904, when he abandoned his studies—as well as the chance to play professional baseball—and decamped for New York in pursuit of an art career. There, he fell in with Robert Henri and a group of urban realist painters that would become known as the Ashcan School.

With aggressive strokes and a dark palette, the group pointed their paintbrushes toward New York’s restless streets and social spaces, particularly in immigrant neighborhoods, at a time of great transition in the city. It was, according to Henri, an “art for life’s sake,” not “art for art’s sake.”

Bellow’s paintings of boxing matches, which synthesized the kineticism and violence of the late Machine Age, perhaps best encapsulate the energy of the Ashcan artists, and remain among the most recognizable artworks from the group today. “Those pictures, for him, were part of a broader interest in capturing what American life looked like in the early 20th century,” explained Maciejunes.

George Bellows, The Barricade (Second Stone) (1918). Courtesy of the Columbus Museum of Art.

And indeed, for many, it’s by the boxing paintings that Bellows is now remembered. But the scope of his subject matter grew from there—and often, so did his social justice agenda.

He churned out pictures of Penn Station, the Hudson River, and the Atlantic Ocean; he painted portraits of his friends and loved ones, often to unsettling effect; and produced a number of gruesome—and highly controversial—scenes of wartime brutality. For the latter category, as well as other radical images, he turned to lithography, helping to re-legitimize a form of printmaking that was at that time derided by serious artists as a wan, commercial application.

“He had a great breadth of vision,” said Maciejunes. “I’ve always been amazed by that.”

In 2025, the CMA will mount a major exhibition of Bellows’s work to mark the centennial of his death.