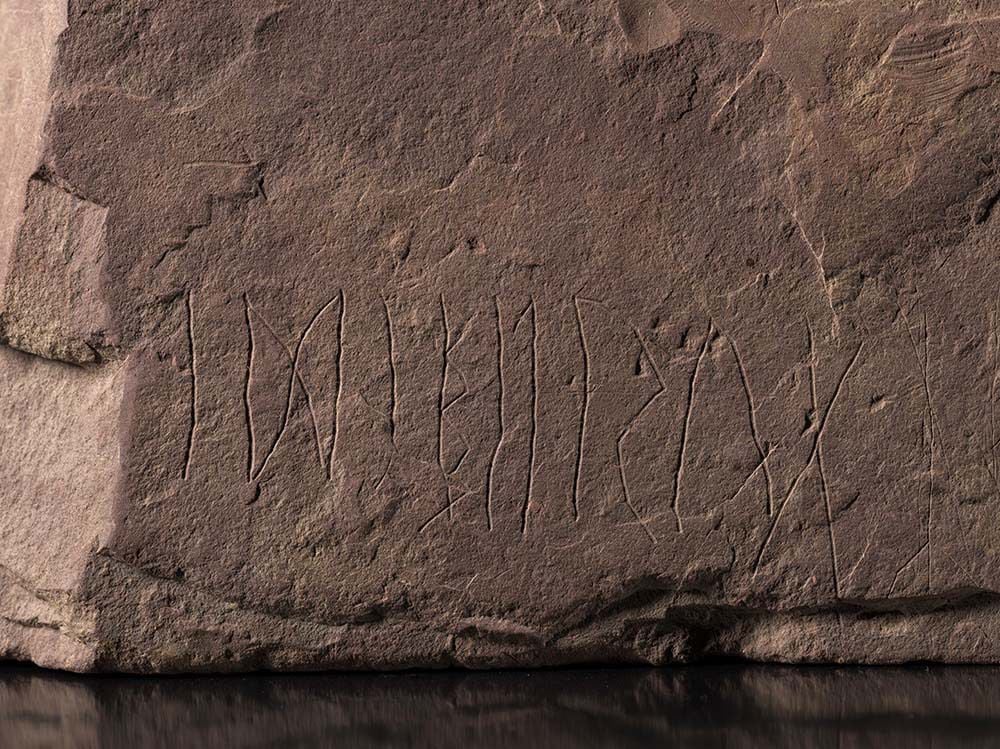

About 2,000 years ago, someone inscribed a series of runes into a square block of sandstone near Lake Tyri, in the Ringerike region of Norway. The person wasn’t the most assured of carvers and not all of what they etched remained legible when the block was discovered late in 2021. Still, their handiwork is now believed to represent one of the earliest known examples of runic writing.

The reddish-brown 12-by-12-inch runestone was excavated by archaeologists from the Museum of Cultural History at the University of Oslo in a grave field close to Lake Tyri. Dubbed the Svingerud Stone after the site on which it was found, it has been radiocarbon-dated to 1 to 250 C.E., during the early Iron Age, making it the world’s oldest runestone.

The Svingerud Stone. Photo: Alexis Pantos/KHM, UiO.

The Svingerud Stone is also remarkable for its face, which bears scribblings—grid patterns, zigzagging figures, and other curious markings—believed to be the oldest runic inscriptions ever found.

“Having such a runic find fall into our lap is a unique experience and the dream of all runologists,” said Kristel Zilmer, a professor of written culture and iconography at the Museum of Cultural History. “For me, this is a highlight, because it is a unique find that differs from other preserved rune stones.”

While Scandinavia has turned up thousands of slabs with Viking Age inscriptions, including the Kjula and Jelling stones, only some 30 runestones have been identified in Norway as originating from earlier eras such as the Roman Iron Age. The Svingerud Stone is the only one to date back to before the 3rd-century.

The runic inscriptions on the Svingerud stone, digitally drawn in white. Photo: Alexis Pantos/KHM, UiO

The runes etched on these stones are the oldest known form of writing in Scandinavia, in use from the beginning of the Common Era until the late Middle Ages. Runic alphabets differed by Germanic regions and periods. Elder Futhark, for example, was prevalent among Northwest Germanic people during the Migration Period (300–568 C.E.), while Younger Futhark, a streamlined version of the script, was used by the Norse in the Viking Age (793–1066 C.E.).

Archaeologists studying the runes on the Svingerud Stone have deciphered a name that spells “idiberug” in Roman letters. According to the team, this could point to a person who is buried in that same spot; the stone was found beneath a grave mound containing cremated remains and artifacts.

“The text possibly refers to a woman called Idibera and the inscription could mean ‘For Idibera,’” said Zilmer. “Other possibilities are that idiberug is the rendering of a name such as Idibergu/Idiberga, or perhaps the kin name Idiberung.”

Illustration of the runic inscriptions on the Svingerud stone. Photo: Kristel Zilmer.

She added that not all of the inscriptions on the runestone can be linguistically decoded: “It’s possible that someone has imitated, explored, or played with the writing. Maybe someone was learning how to carve runes.”

Researchers are continuing to study the runic etchings, just as archaeologists are analyzing other discoveries at the gravesite at Lake Tyri. As Zilmer told the Associated Press, their work will offer “valuable knowledge” about early runic writing as much as the custom of runestone construction.

The Svingerud Stone will be exhibited at the Museum of Cultural History through February 26.

More Trending Stories:

Art Industry News: Online Critics Lambast Hank Willis Thomas’s ‘Insulting’ Martin Luther King Monument + Other Stories

German Researchers Used Neutrons to Peek Inside an 800-Year-Old Amulet—and Discovered Tiny Bones