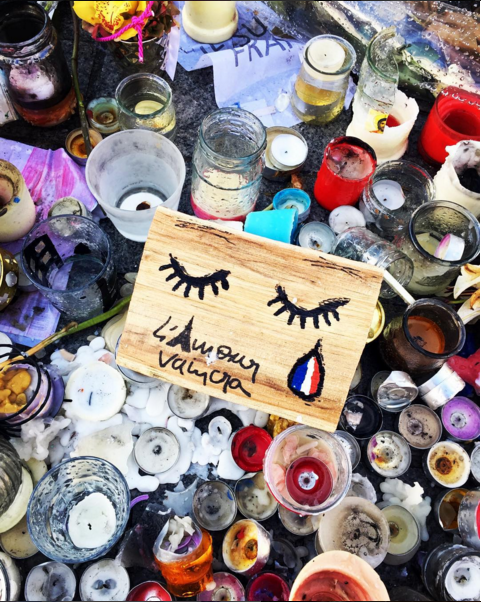

In the aftermath of the November 13 terrorist attacks in Paris, grieving family, friends, and even total strangers of the 130 people killed created impromptu memorials on the streets of the city—a familiar act that has taken place around the world following times of unspeakable tragedy. But what happens to those mementos once cleaners inevitably sweep the streets and allow citizens to move on with their lives?

In a New York Times profile, Parisian archivists discuss the process of sifting through tens of thousands of artifacts—things like poems, letters, drawings, flowers, photographs, and origami cranes—in order to create a picture of the harrowing event that will eventually prove valuable for historians and sociologists.

“We need to leave some of the objects, and at the same time, we need to make room for the sidewalk, sometimes even the road, so that life can go on,” says Guillaume Nahon, director of the Paris Archives. “It’s a day-to-day process, and a contradictory one too, because these memorials are supposed to be ephemeral, but people still need a place to mourn for now.”

While many of the memorials that sprang up in New York following the 9/11 attacks were archived, the effort is new for Paris. None of the materials from memorials following the Charlie Hebdo attack, which took place in January, were officially archived. The library at Harvard University recently initiated an effort to collect such artifacts, but the task becomes significantly more challenging as time passes.

This time, the city quickly organized an effort to ensure the materials from the November 13 attacks were not lost. Many of the archivists are working as volunteers. Their focus has been on collecting letters and drawings, which are of particular importance as historical artifacts.

“What you always find, in all the attacks I’ve studied, is that people invoke love and peace,” says sociologist Gérôme Truc, who is working on a book that tracks human responses to deadly terrorist attacks. “If you don’t have these documents, you completely lose access to that dimension of things.”

Once plucked from the streets, the documents are taken to the Paris archives, where they will undergo a rigorous conservation process that includes being disinfected and often dried to prevent mold, and then inventoried and in some cases digitized. Amidst the relics, the archivists note, are hundreds of untold stories that bear quiet significance.

“When we arrived on the first spot, at La Bonne Bière, I could not help myself and I read some of the messages,” said Emilie Legrand, who oversees restorations at the Paris archives. “The one which struck me the most was the business card of a doctor, who wrote that he was sorry he was not able to save one of the men he tried to help after the shooting.”