During the 10 years he spent working at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, author Patrick Bringley developed a profound, in-depth appreciation for the vast art and antiquity collection at one of the largest and most popular museums in the world. He made the most of his unrestricted access to immerse himself in art ranging from Greek and Roman antiquities, Chinese silk paintings, and Old Masters, to American art, Impressionist and modern, postwar, and contemporary works. Whether it was the experience of standing in awe and quiet contemplation in front of the artworks or furthering self-education by delving further into their history and context with supplemental research, he clearly made the most of his time there.

But Bringley didn’t join the Met as an executive, a curator, or even as an art expert. In 2008, he joined the museum as one of the hundreds of blue-jacketed security guards charged with guarding some of the world’s rarest treasures. And he did so after making a leap from a high-profile job at another august city institution, The New Yorker, a move that coincided with the tragic loss of his brother Tom, the older sibling by two years who he admired and looked up to his entire life. It was after Tom’s death from terminal cancer at the young age of just 27, that Bringley felt the need for a life change, and he found it in the hallowed halls of the Met, where the job of guarding the masterpieces helped him to find solace, quiet, and ultimately, healing.

Brinkley writes: “When in June of 2008, Tom died, I applied for the most straightforward job I could think of in the most beautiful place I knew. This time, I arrive at the Met with no thought of moving forward. My heart is full, my heart is breaking, and I badly want to stand still awhile.”

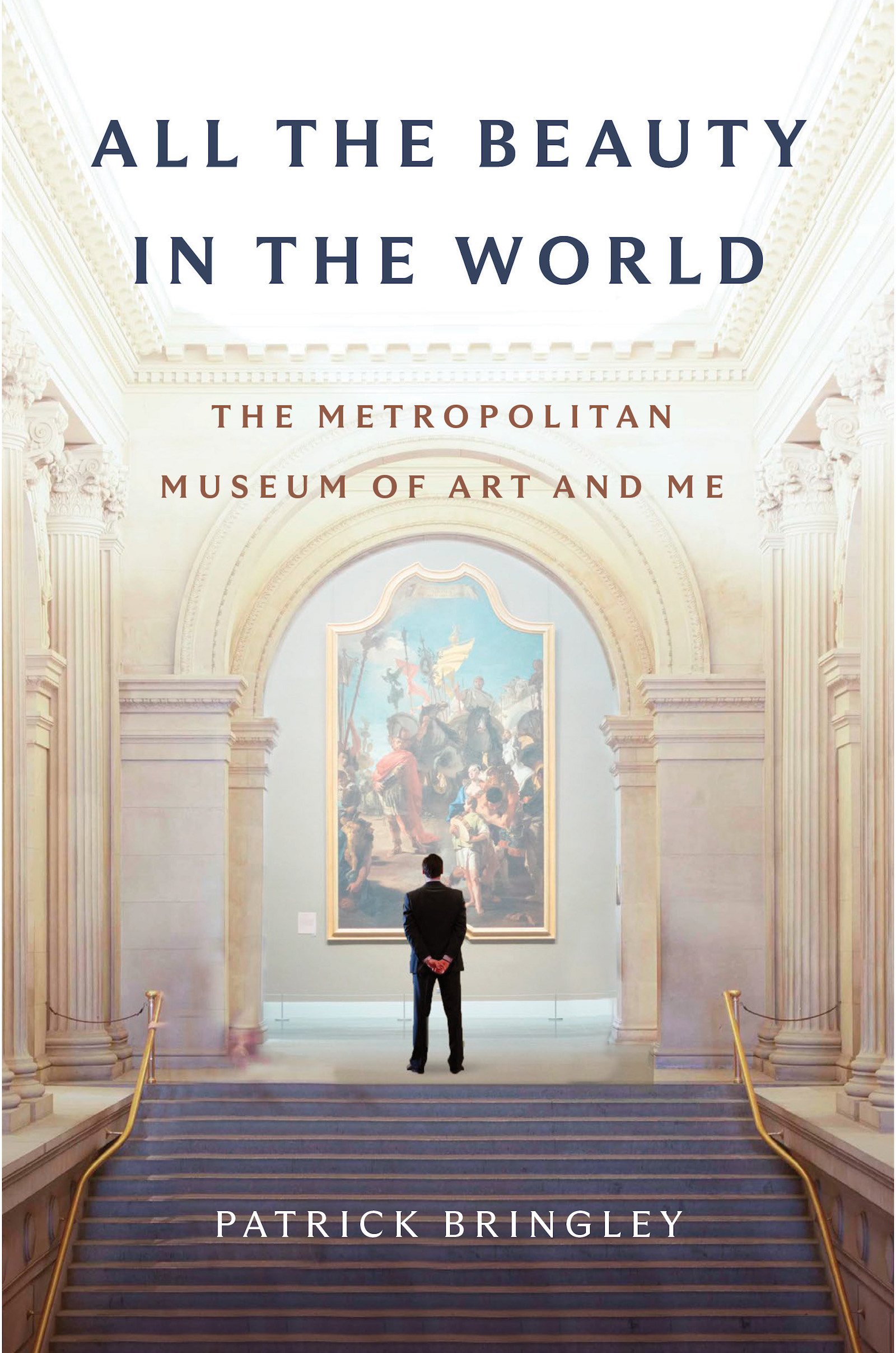

From guarding the art, to watching millions of visitors from around the world (and no shortage of locals) stream up the grand staircase each year, to making friends on a diverse team of about 600 fellow guards, Bringley’s book, All The Beauty In The World: The Metropolitan Museum and Me (Simon & Schuster), is not a tell-all. It is more a love letter to one of the world’s most beloved institutions. As an added bonus, Bringley, who left after a decade, is now leading tours of the Met, with an appendix to his book listing every single artwork referenced in the text to help curious visitors find them inside the museum.

Author Patrick Bringley. Photo: Jason Wyche.

Don’t miss our recent podcast interview with the author on The Art Angle. And here are just a few of our favorite highlights, encounters, and takeaways from this fascinating read.

You Don’t Forget Your First Visit to the Met

Most Met lovers would agree—and Bringley recounted in vivid detail his first visit to the museum at age 11, on a trip from Chicago with his mother. “I remember a long subway ride to the remote-sounding Upper East Side, and I remember the storybook feel of that neighborhood: doormen in livery, proud stone apartment towers, wide famous avenues—first Park, then Madison, then Fifth… The magical part was that as we drew nearer it kept growing wider and wider, so that even out front by the hot dog carts and the geysering fountains, we were never able to get the entire museum into view. I immediately understood it as a place of impossible breadth.” Bringley’s very solid advice to new and first-time visitors is to just wander. As he pointed out, the development of the museum since its opening in 1880 “expanded in a largely illogical sprawl, appending new wings to old ones in such a way that entire new atmospheres seem to spring up out of nowhere.”

Co-Workers From All Walks of Life

While Bringley entered the job as something of a silent observer, he started to develop close friendships with the tribe of fellow guards he meets over the course of time. As he pointed out: “The glory of so-called unskilled jobs is that people with a fantastic range of skills and backgrounds work them. White-collar jobs cluster people of similar educations and interests… At the Met, I knew guards who have commanded a frigate in the Bay of Bengal, driven a taxi, piloted a commercial airliner, framed houses, farmed, taught kindergarten, walked a beat as a cop, reported a beat for a newspaper, and painted facial features on department store mannequins. They are from five continents and five boroughs… And remarkably, it doesn’t feel disorienting to stand on points with just about any of them. The ice is already broken. We’re wearing the same clothes.”

A factoid that may surprise readers? The Met keeps a tailor in-house just for the guards and their uniforms.

The Visitor ‘Types’

At the height of Bringley’s pre-pandemic guard days, he noted the museum was welcoming almost seven million visitors a year, “a greater attendance than the Yankees, Mets, Giants, Jets, Knicks, and Nets combined”—more even than the Statue of Liberty or the Empire State Building, though less than the Louvre in Paris.

“There is no one way that visitors experience the museum, but there are a few typical ways,” wrote Bringley. These include the “Sightseer, perhaps a dad in his local high school’s windbreaker, camera around his neck, on the hunt for whatever’s most famous… There is the Dinosaur Hunter—a mother with small children who cranes her neck to peer around corners, panicked by each new piece of evidence that this museum only has art.”

Before you mistake any of these encounters for anything resembling an eye-roll, it is immediately apparent in both the introduction of the “types” and elsewhere in the numerous visitor encounters sprinkled liberally throughout the book that Bringley’s guidance is never anything short of curious, kind, non-judgmental, and generous.

Contemplating Life and Death in the Egyptian Wing

Bringley reflected on the Egyptian wing as “a singular place to work. It is a huge section with room enough to display almost all 26,000 objects,” making it the envy of most other curatorial departments. Amid fielding questions about whether or not the artifacts are “real” or observing visitors’ stunned reaction at being informed that some objects are 5,000 years old, he also answers questions from children wanting to know why the mummies are not unwrapped:

“There’s a dead dude in there?”

“Who killed him?”

“Who said anyone killed him?”

“What’s he look like under it?”

They prompt the author to ruminate on the mummification practice itself. He wrote: “A minute later they bolt from the room, and I’m left behind to reflect on how ugly the mummifying impulse was, what a failure, what a brazen, feeble denial of a fundamental truth. The body doesn’t make it. Believe all you want that some piece of a person is immortal, but a significant part is mortal, inescapably, and mad science will not stop it from breaking down.”

What We Can Learn From Looking Closely at Old Masters

Sketch by Maya McMahon

While the wealth of knockout, up-close, and personal encounters with art described in the book are too many to count, one that stands out is Brinkley’s description of Florentine painter Bernardo Daddi’s Crucifixion, in which the body of Christ is “dignified but limp; a gentle elegance in his bearing suggests that he suffered bravely,” as Mary and John sit reflectively on the ground.

“An artist in the 14th century wouldn’t have dreamed that one day there would be art connoisseurs and textbooks dedicated to something called art history,” he wrote.

While contemplating his own intent at examining the work, and alternately, the artist’s intent in creating it, he concluded: “Much of the greatest art, I find, seeks to remind us of the obvious. This is real is all it says. Take the time to stop and imagine more fully the things you already know. Today my apprehension of the awesome reality of suffering might be as crisp and clear as Daddi’s great painting. But we forget these things. They become less vivid. We have to return as we do to paintings, and face them again.”