Fluidity, in a literal sense, has run through Patty Chang’s art for decades. From shaving her pubic hair with seltzer water for a 1998 performance to creating urinary devices with plastic bottles while traveling across an aqueduct in China for her recent project Wandering Lake, liquids in all forms have found ways into the artist’s work.

“In the beginning of my career,” she says over Zoom from her Los Angeles studio, “accessibility was a main factor for me to use bodily or commercial fluids.”

The type of liquid she uses in her most recent video installation, Milk Debt, which is on view now at Pioneer Works in Brooklyn, New York, stems from her confrontations with her personal anxieties. In a five-channel immersive orchestration that first premiered in Santa Monica in December, women pump their breast milk while reading lists of worries submitted by anonymous people in Hong Kong and the U.S.

A mother herself, Chang saw a parallel between releasing one’s anxieties and the act of lactation, both a biological and emotional process. “It affects your whole body, including your mind,” she says.

The previous version of Milk Debt, based in California, concerned Chang’s anxieties about living in L.A. over the past few years. Now, the work includes fears she collected from New Yorkers after the pandemic.

“Milk Debt” by Patty Chang, installation view at Pioneer Works. Photo: Dan Bradica.

The project stems from a day Chang spent at the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino. Ostensibly she was there to research California’s water infrastructure, but as time wore on she noticed herself worrying about the environment. Although she was born and raised in the Bay Area, her fears about the environment were heightened after moving back to the West Coast a few years ago. “It may be the incredible heat, the fires, or the traffic,” she says.

She began to scribble down highly personal truths—ones she calls “speculative and irrational”—about herself in a notepad with the Huntington’s letterhead, which at first felt both subversive and inspirational. First on her list of fears was the possibility of her eight-year-old son dying, which she then followed up with broader concerns, such as drought and “eating maggots.” (She later realized that this fluctuation between the intimate and universal would be a common thread among many people’s fears.)

Chang didn’t know at the time what she would do with the list. But uncertainty is how she has begun most of the projects in her two-decade multidisciplinary career. “Having to figure out the unknown while starting a project has always been a challenge,” she says.

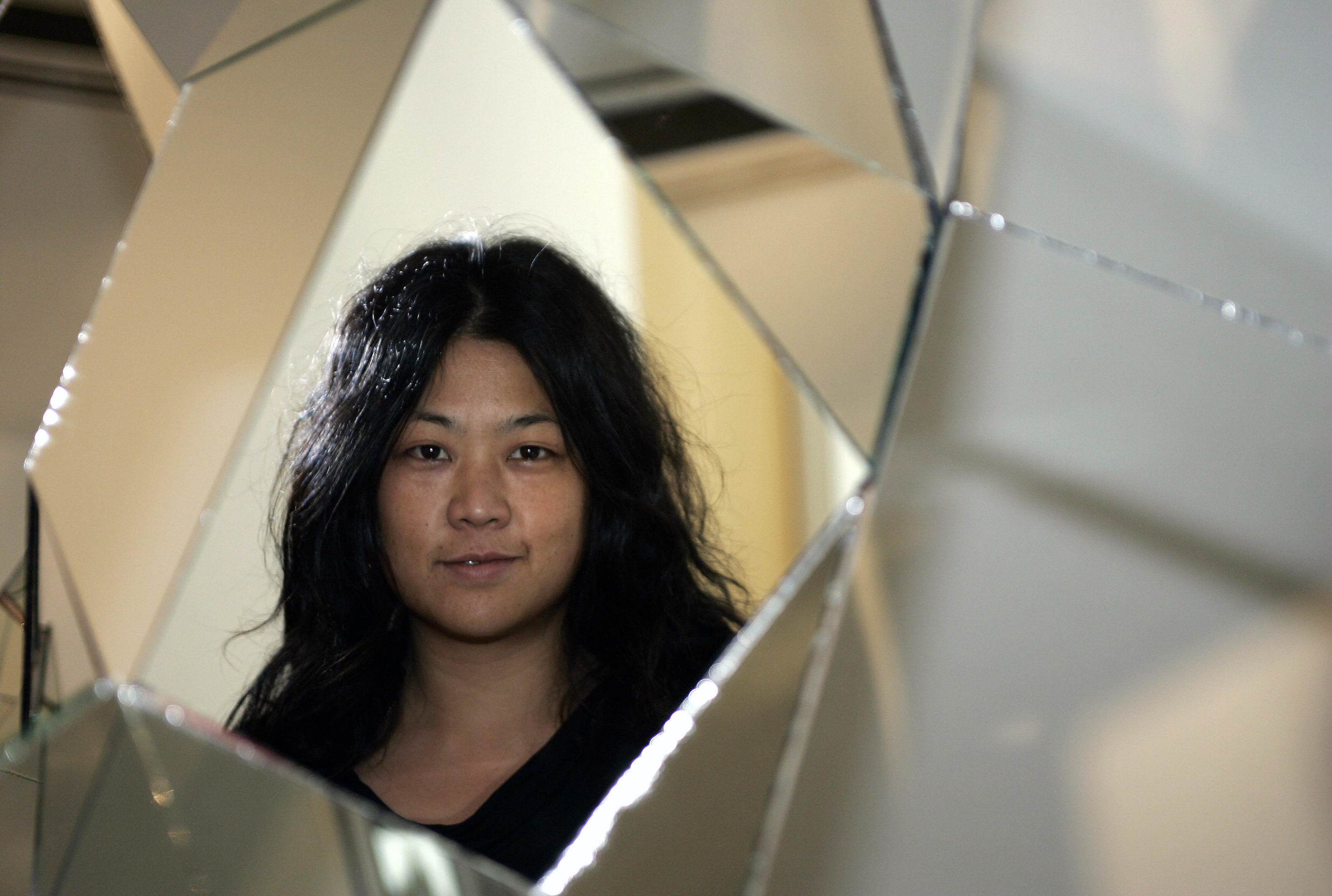

Patty Chang, Melon (At a Loss), SD video still (1998).

When Chang emerged in the late ‘90s with endurance-based performances, she had to use her own body along with a few (occasionally liquid) props in front of the audience. She once ate raw onions with her parents, and had an eel crawl inside her shirt. A Chinese-American, Chang interrupted the trajectory of body art, which had emerged as a sub-category of performance art with a strong emphasis on endurance, in the 1960s. While female visibility was central to the movement—led by artists such as Marina Abramović and Gina Pane—Chang took inspiration from Yoko Ono’s iconic Cut Piece from 1964 to comment on the invisibility of Asian bodies in America, as well as to challenge the stereotypical timidity associated with Asian women.

In her video piece Melons (At a Loss) (1998), Chang cuts through her bra with a knife while ritualistically discussing her aunt’s death. The shock of the apparent mutilation is eased when melons are revealed inside the bra rather than flesh. Poking the fruit, she pulls out its meat and places it onto a plate sitting atop her head. While subverting notions of skin color, family lineage, and exoticization of the body, Chang seems confident and determined. But, she recalls, “I never liked performing directly in front of the people.”

Acquiring a studio and a camera was, therefore, “a relief moment,” she says. When she delivered her first performance for the camera in her 1999 video Fountain, she used the lens to trick the eye and shoot her own reflection in water vertically. The artist drinks from the mirror-like water, sipping her reflection in an homage to art history’s representation of the self-portrait and the myth of Narcissus. Today, the work taps into notions of self-indulgence and image obsession within the social media-dominated landscape.

Around 2004, Chang left the studio and went outdoors to capture various social and environmental unrests—from China to oil sands in northern Canada to the Aral Sea in Uzbekistan. The first time she hired actors for a project was in China’s Yunnan province, in a city renamed after the mythical Shangri-La to boost tourism. She built an imaginary snow mountain in homage to James Hilton’s novel Lost Horizons and shot locals transporting the replica around town.

Patty Chang’s sculpture Shangri-La, of a mirrored mountain mounted on a rotating platform, at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. Photo: Jeff Haynes/AFP via Getty Images.

“Humor is a strategy that makes people aware and also uncomfortable,” she says about her subversive approach to narrative. “There are a lot of strange things that we don’t pay attention to, but I try to extract them. Deep down, I am interested in communication.”

By delegating on-camera jobs to others in much of her recent work, including Milk Debt, Chang has been able to explore sides of it that she couldn’t see while she was at the center. For example, after hiring professional actresses for the work (through a lactation activists’ group in Hong Kong and an online call in L.A.), she realized that one woman had difficulty delivering her lines the moment she started pumping milk.

“She switched to another space when the lactation caused her to release hormones,” Chang said. “There seems to be another relationship between the body and the mind during this process.” She then brought in a teleprompter for the actresses and, eventually, the vertically scrolling text became a part of the work, too. She hopes providing the audience with the list of worries within the installation help them internalize the content.

“Milk Debt” by Patty Chang, installation view at Pioneer Works. Photo: Dan Bradica.

Sharing her fears publicly has been both meditative and revelatory, Chang says. “I started thinking about the visibility of things we usually keep below surface.” Worries she amassed from others during Hong Kong’s political turmoil, or the early days of the pandemic in New York reflect both the universality and particular nature of human fear. “A scare about online identity theft comes after one’s facing of their cat’s death,” she says.

She chose the title for the work from a section in David Graeber’s book Debt: The First 5000 Years, about the Chinese Buddhist belief in the impossibility of repaying one’s mother for her life-giving fluid. A fluid tension between the spiritual and the real echoes throughout Chang’s work as she invents new ways for us to meander through toward discoveries, including the broad meaning of debt itself. “We can never pay for what the earth has given us,” she says, “but do we even consider this a debt?”

“Patty Chang: Milk Debt” is on view at Pioneer Works through May 23, 2021. Reservations are required.