“If it were not for Deborah Willis,” artist Dawoud Bey says near the end of Thomas Allen Harris’s documentary Through a Lens Darkly: Black Photographers and the Emergence of a People, “we all would have disappeared at some point.” It’s a powerful statement, one that crystallizes the issues underlying the film, which is produced by Willis and based on her 2000 book Reflections in Black: A History of Black Photographers 1840 to the Present.

The crux of the film, articulated in a recording of James Baldwin that plays during the opening moments and gets reiterated in different guises throughout, is that photography has been a crucial tool for self-representation and self-making used by members of the African Diaspora since they arrived in America. It has also been a field of struggle on which African Americans have sought to wrest control of how they are portrayed from whites.

Works by contemporary artists Harris interviews, including Carrie Mae Weems, Glenn Ligon, Lorna Simpson, and Hank Willis Thomas (Deborah Willis’s son), make plain how this fight for the right to control the means of one’s self-representation continues to this day. Even if Harris’s frequent autobiographic interjections and ruminative monologues hamper the film, his subject matter is sufficiently engaging to make up for these blunders, particularly as it dovetails with issues raised by the ongoing fallout from the murder of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri.

Thomas Allen Harris, director of Through a Lens Darkly, a First Run Features release.

Photo by Russell Frederick for Chimpanzee Productions, Inc.

One of the film’s strengths is that it doesn’t rely on current examples and boldface names, but instead offers a crash course in the history of African American photographers. Unsurprisingly, the overwhelming majority are men, though a chapter late in the film does a bit to right the gender imbalance. Harris’s narrative begins with Jules Lion, who opened a daguerreotype studio in New Orleans in 1840 and is credited with being the first African American photographer. The lack of academic interest in tracking down what remains of Lion’s output, which historians Harris consulted attest to, makes plain the racism still shaping the field.

An especially fascinating passage is devoted to the period immediately after the Civil War. Here we see African American soldiers returning from battlefields where they have literally been fighting for their freedom, and flocking to photography studios to have their portraits taken as records of their heroism and testaments to their full citizenship. During the same period, Harris and Willis show the genesis of the African American “thug” stereotype in the popular press and mainstream photography of the day. Holding up the threat of the black thug became a new way for whites to control African Americans at a time when they had achieved an unprecedented degree of power to determine their own representation.

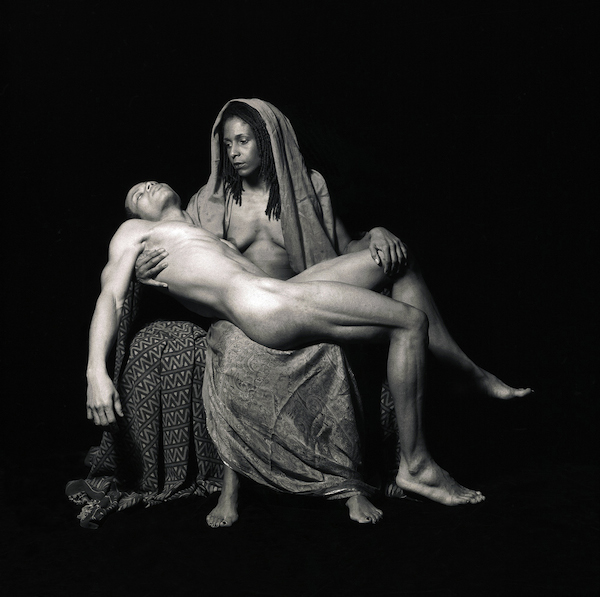

An untitled photograph by Lyle Ashton Harris in collaboration with Thomas Allen Harris, as seen in Through a Lens Darkly, a film by Thomas Allen Harris. A First Run Features release.

The post-Civil War period’s duality between images portraying African Americans as either exemplary citizens or dangerous criminals endures, as made plain recently by the #IfTheyGunnedMeDown hashtag that spread like wildfire following the murder of the unarmed teenager Michael Brown by a Ferguson police officer last month. Taking to Twitter, young black men and women juxtaposed images of themselves graduating from high school or college, embracing relatives, or performing other noble rites of youth, with photos in which they’re drinking or smoking, making gang signs, or indulging other stereotypically “thuggish” behavior.

Hashtagging the homespun photo diptychs #IfTheyGunnedMeDown, young African Americans asked which photo the media would use to represent them. In so doing they are rephrasing for the 21st century the 1963 James Baldwin quotation that opens Through a Lens Darkly, and that orients the film: “Every negro boy, every negro girl born in this country until this present moment undergoes the agony of trying to find in the body politic, in the body social, outside himself or herself, some image of himself or herself which is not demeaning.”

Through a Lens Darkly continues at Film Forum in New York City through September 9.