In the spring of 2020, British opera singer and broadcaster Peter Brathwaite found himself like most everyone else, wandering his home and wondering how exactly he was going to pass the coming days. The baritone, who typically had a busy calendar of performances at major opera houses throughout Europe, watched as, day by day, his commitments, one by one, disappeared from the calendar.

Brathwaite’s talent for performance would soon find another outlet. Scrolling social media, he noticed a fascinating trend: ordinary people stuck at home were recreating famous artworks from various odds and ends at their disposal. The Getty Challenge, as the phenomenon was known, started as a creative prompt from the Getty Museum and quickly became an internet sensation. Brathwaite, who had been independently researching his family’s heritage in Barbados, thought the challenge might be a good performative outlet for some of his findings.

Soon Brathwaite made his first recreation, an 18th-century portrait of a Black servant. And then he made another, and then another. In fact, the more he made, the more he found himself learning about the complex history of Black portraiture. His still ongoing project, Rediscovering Black Portraiture, came to span dozens of images from around the world, ranging from Ethiopia to Tudor England to the contemporary United States.

Brathwaite is now working on a book about his project with the Getty Museum (slated for spring 2023) and recently organized an outdoor exhibition of his portraits for King’s College London’s Strand Campus.

We spoke with Brathwaite about what the project has taught him, the props with the most personal significance to him, and why there’s still work to be done

The Virgin of Guadalupe (1745) by an anonymous artist, made after the statue of the Virgin of Guadalupe in Extremadura, Spain. Braithwaite made his reconstruction with his grandmother’s patchwork quilt, grandfather’s cou cou stick, tinsel, and Barbados doll. Courtesy of Peter Braithwaite.

You began Rediscovering Black Portraiture during the early days of quarantine. What was the first artwork you recreated? What drew you to it?

Every day I was watching work disappear out of my diary and I was looking for a way to take my mind off world events. At the time, I was researching much of my family history, which was occupying my time. The Getty Challenge seemed like a good opportunity to bring some of that research to life. It let me think about the lives of some of my Black ancestors who, when they were mentioned in records, it was without any fullness and complexity. From the period of enslavement, they tend to be named in ledger books, or if they are mentioned, it’s in relation to their white owners. It was interesting for me to look for images from an era that coincided with my family history.

The first work I recreated was an 18th-century painting of a servant in England. It’s a young Black child depicted with a lapdog and he’s holding a glass of wine and a silver tray. At first glance, it seems perfectly innocuous and pleasant, but when you delve deeper, you can notice how he is treated like another object—commodified, like the glass and the silverware. The painting is entrancing at first because it looks as if he is happy. But scratching beneath the surface, you realize there’s something more complex at play.

Detail of Édouard Manet’s Olympia (1865). Here, Braithwaite focuses on Laure, the Black model in the image, known for her work with Manet. He has reworked his images with lilies, roses, and a selection of family historical documents. Courtesy of Peter Braithwaite.

Have you always been interested in this sort of research, and stories about other people?

In my musical work, as a performer and opera singer, I’ve always been attracted to stories that haven’t been told, and voices that have been silenced. I created a musical project based on the “Entartete Musik” exhibition that the Nazi party held in Germany in 1938, of music that was banned in Germany since 1933. The exhibition included music interspersed with historical texts, such as snippets of the exhibition brochure, text, and other elements of propaganda.

I think what that project showed me is that there is still much to learn from historical moments like that one. Often the voices that are silenced and attacked are the ones that are speaking for the disenfranchised and the marginalized. The parallel between that exhibition and these portraits is that much of this work hasn’t been shown or seen or spoken about. These portraits tell us a lot about those difficult areas of history that we don’t often speak about.

We are still learning about Black lives across these eras and I’m trying to piece together the fragments. These fragments have enabled me to draw parallels and imagine these lives in the face of the silence of history. That’s hugely healing but also restorative and brings the element of justice to the table as well. Who are these figures? Allegorical or drawn from life? They allow us to chart the history of Black subjects in art and imagine these lives.

Agostino Brunias, The Barbados Mulatto Girl (1779). Braithwaite has reworked his scene with his grandmother’s patchwork quilt and a Caribbean map.

Courtesy of Peter Braithwaite.

How do you find the works that you recreate? Do people send you suggestions now?

In the beginning, I wasn’t working in any sort of chronological order. I was experimenting with different search terms. And what happens when you put phrases and words into Google? That is a whole study in itself. A lot of the research was guided by that. I was taking elements of words that I was finding in my family tree research and putting them into Google.

For example, my mixed-race great-times-four-grandmother, Margaret Brathwaite, is recorded as being a “mulatto”—an obviously offensive term. But putting the word into Google and seeing what turns up, surprisingly, artworks are still labeled with that term. One of the works I recreated is The Barbados Mulatto Girl. That was hugely fascinating to me, to see this image of someone who was like my grandmother. It’s this tremendous entry point into a whole history of representation and language, what people were receiving in Europe from a colonial outpost like Barbados. With that specific work of art, we are confronted with conversations about colorism. Colorism was more or less invented in Barbados through the colonial hierarchies that existed based on how people looked, the color of their skin and their racial makeup.

There was one period, too, where I had found an image from one of the French Caribbean colonies, that led to an interest in looking at images leading up to the French Revolution and how Black people played a role in the propaganda that was being produced. Then other people would suggest things and say, “Have you seen this?” It was a bit like a Spotify effect: if you like this, you might like this.

William Ward (after Mather Brown), Joseph Bologne de Saint-George (1787). Joseph Bologne was a composer, violinist, conductor, and fencer. Braithwaite constructed his interpretation with a book of Barbados folk songs, an oven mitt, and his grandfather’s cou cou stick. Courtesy of Peter Brathwaite.

Where did you find your props and costumes? Were any of the objects particularly significant?

Everything is from my house. I’ve collected a lot of junk over the years. Some things were made. At the very start of the project, I was reluctant to make things, but I gradually became more amenable as the costumes became more complicated. I also used the portraits as a platform for objects that have existed in my family for generations.

One of these objects was my Barbadian grandfather’s cou cou stick, which looks like a small cricket bat. The cou cou stick is used in the cooking of the Barbados national dish, which is made of cornmeal and water and often has chopped okra. It’s boiled for a fairly long time and the cou cou stick is used to get rid of any lumps in the mixture. This dish has West African roots. It traveled, like okra, across the Atlantic. It evokes memories of past freedoms, and there is an active resistance to its very existence. Having the cou cou stick in my recreations has been powerful and uplifting, especially in the face of the traumatic elements, that many of these paintings hold. That’s something that I’m conscious of in the recreation of these works: that I’m not perpetuating the colonial violence that exists within them.

I’ve also included a quilt in many of these works—it is a memory of my grandmother. She created it. The quilt links directly to West African fabric craft traditions. So there are insignificant objects in these recreations, but there are also objects that underline the project as a whole. There is another side to history. It isn’t just about enslavement. There are elements of the culture that have survived. I like to celebrate those moments, make a celebration of the people, the humans as the center of these works.

Have you made any observations about the way that Black people are presented across art history?

It’s easy to say there is a natural progression from invisibility to visibility, but there are little things that disturb the progression. It isn’t linear. In this series, you stumble across figures, whether in the Tudor age or later in the 18th century, who were painted because they had managed to surprise and challenge the stereotypes.

For instance, Adolf Ludvig Gustav Fredrik Albert Couschi, also known as Badin the “trickster,” was an Afro-Swedish intellectual. He is often called a court servant to the Swedish Royal family. He was adopted into the family. His image is so insightful because it, he shows his intelligence, his wit. He’s pictured with a chess piece—in fact, a white chess piece that speaks to what he’s trying to say to us. He’s turning things upside down and he’s controlling his own narrative. But at the same time, we can’t forget that he was trafficked from the Danish West Indies to Sweden by a sea captain, and no doubt experienced trauma throughout his life. But we do see him smiling. There are all these things that we’re weighing up in the portraits. Finding an image like that was a huge surprise for me.

A detail of Bisa Butler’s Africa The Land Of Hope and Promise For Negro Peoples of the World (2019), which is a quilted portrait of Emmett J. Scott. Braithwaite’s recreation is made with face paints and African wax fabric offcuts. Courtesy of Peter Brathwaite.

Are there any eras you’ve particularly enjoyed recreation?

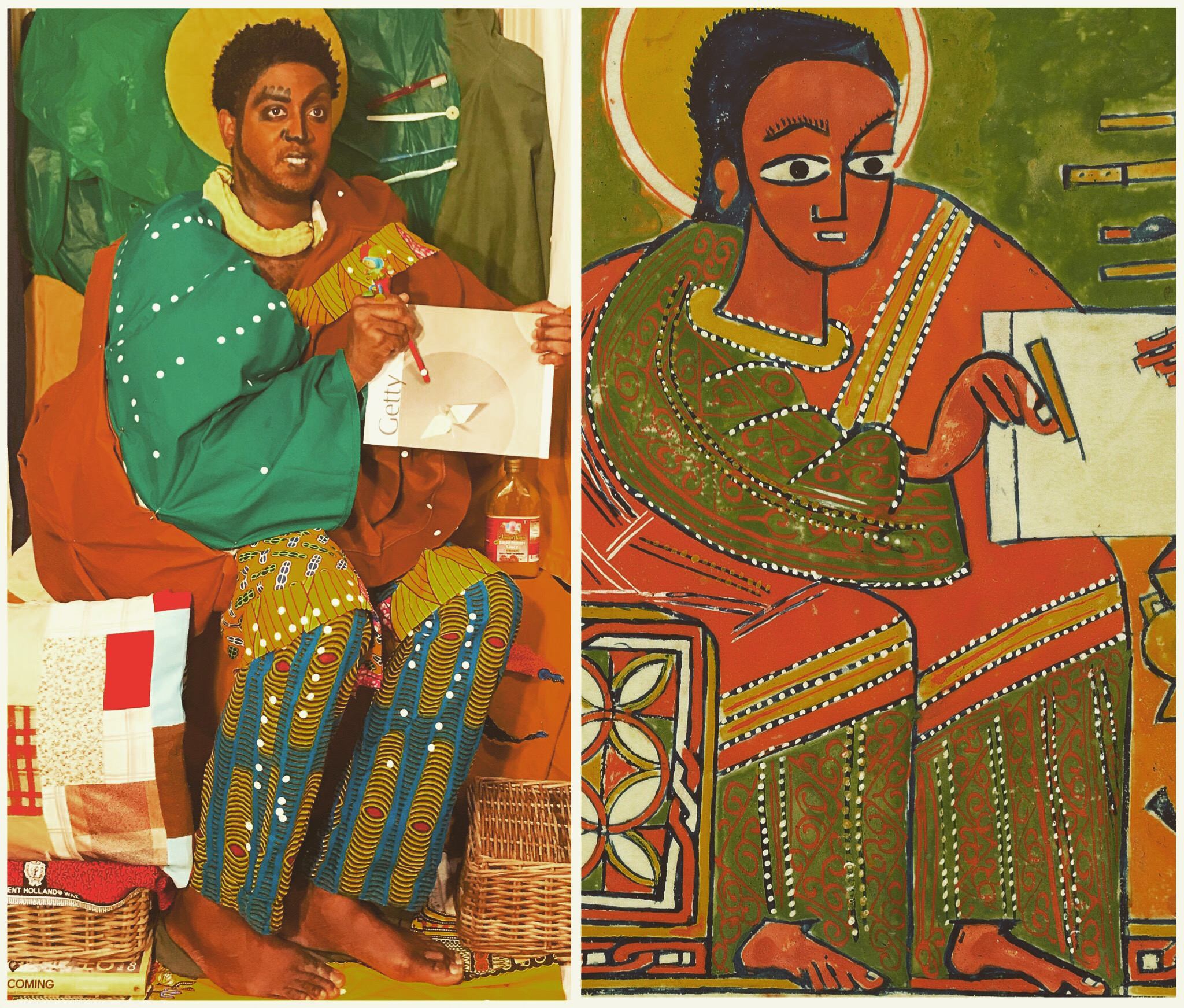

I enjoyed recreating the Ethiopian gospel book because it was created by a Black artist within the culture. The style is graphic, otherworldly, and completely one with the culture. It is very different from say the image from the Abbreviatio of Domesday Book, where we see the Black figure hanging on for dear life, it seems, to a capital letter ‘I’ that decorates the start of a page.

Showing how Black artists have taken the narrative into their own hands is vital to this project. Encountering the work of British artists like Sonia Boyce is hugely uplifting, especially when viewed in relation to images where Black figures exist on the margins. Or the work of Bisa Butler, whose quilts are of people who have been marginalized or forgotten, and she’s reclaimed the images, and is centering them. These works bring balance to the project, which otherwise could be an amplification of trauma.

John Thomas Smith, Joseph Johnson (1815). Braithwaite reworked the scene with cardboard, a mop, and an Afro print flag. Courtesy of Peter Braithwaite.

Do you think your career as a performer has made you more suited to this project in any way?

My approach is based on how I work as a performer and the different layers of research that go into creating a performance. My concerns are: Who am I speaking to? What dialogue can I create by putting on this performance? What am I trying to say? And how can I make the work a platform for education? I’m learning new things all the time by looking at these images, and I hope people are finding it a useful way into lesser-known histories.

I think it’s about how we imagine ourselves and where we see ourselves going. Whether it’s fragments of heritage, or contested heritage, or forgotten aspects of heritage—how can these be useful to us moving forward in light of Black Lives Matter? What can we learn from this work? I think of this work as being active, rather than passive. It’s always asking questions, and those questions change as we change. I go back to some of the works and I see something that I didn’t see initially. I like to maintain this feeling that there is forward motion, that the works are never really finished. There’s always something more to say, and it could lead to something else. That’s the same as performance.