Nearly a decade after Richard Nixon won the White House in 1968 with merely 43 percent of the popular vote, nine years after the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy, four years after Lieutenant William Calley received a presidential pardon for killing twenty-two Vietnamese civilians, and three years after the Watergate scandal brought down the nation’s 37th President, painter Philip Guston confessed his frustration as an abstract artist to an interviewer from the New York Post:

The war, what was happening to America, the brutality of the world. What kind of man am I, sitting at home, reading magazines, going into a frustrated fury about everything—and then going into my studio to adjust a red to a blue? I thought there must be some way I could do something about it.

Besides turning from abstraction to figuration in 1971—setting off an art world scandal that rivaled the one that broke out when Dylan went electric—Guston also penned a suite of ink drawings that savaged America’s most detestable president.

Acid but weirdly compassionate, public-minded yet explicitly profane, they remained mostly unknown until their posthumous publication in book form in 2001 as Philip Guston’s Poor Richard—the artist’s satirical nod to Benjamin Franklin’s encyclopedic alter ego in Poor Richard’s Almanack.

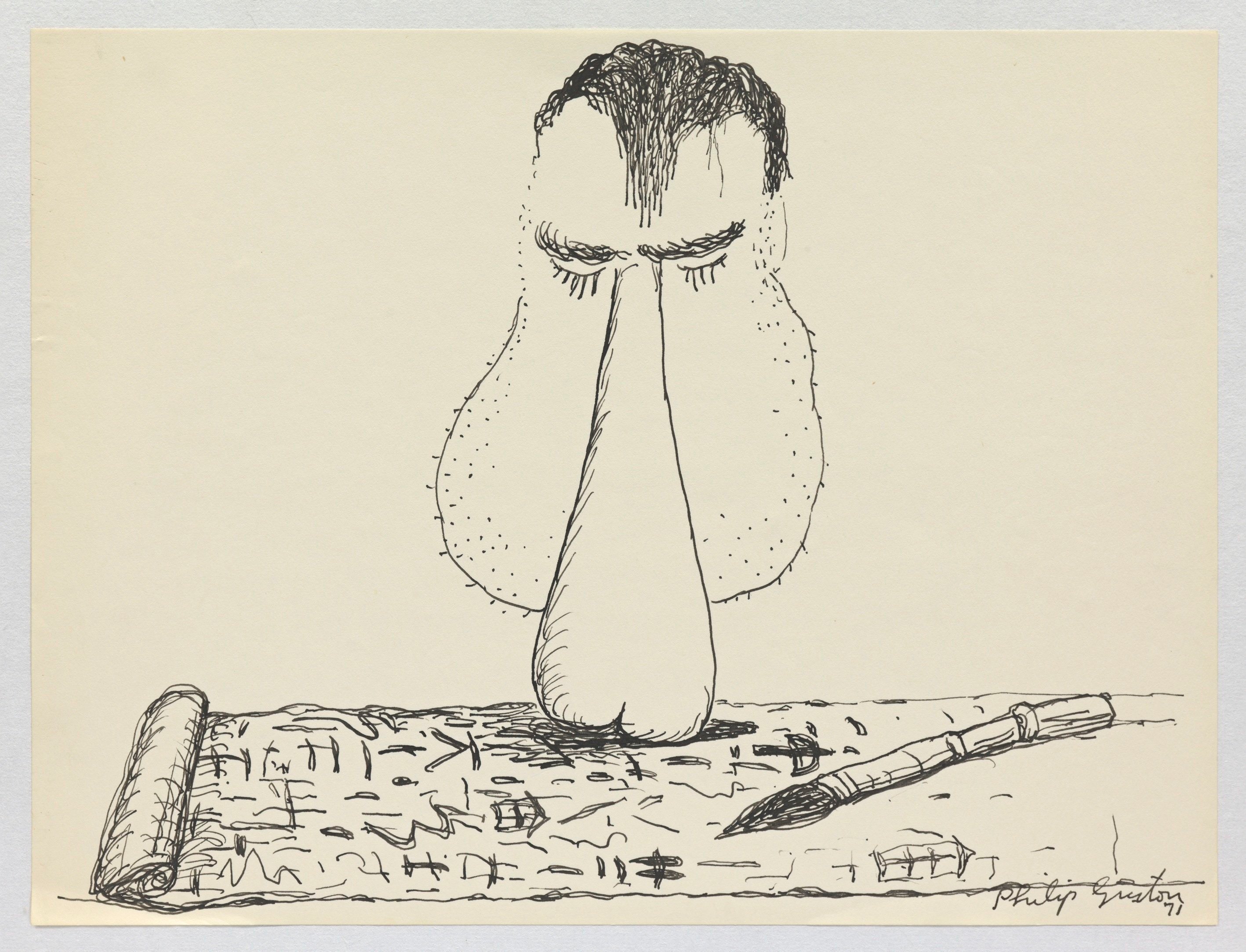

Philip Guston, Untitled (Poor Richard) (1971). © The Estate of Philip Guston. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

Despite the fact that Guston dutifully selected and put together 73 of these drawings in a book-like chronology—in no small part as a riposte to his friend Philip Roth’s own Nixon-bashing novel Our Gang—the painter held off publishing or exhibiting the images during his lifetime. Astoundingly, for someone as profanity-proof as Guston, he remained gun-shy about his modern-day Caprichos—a consequence, no doubt, of the shellacking he’d received from the New York art world for quitting Abstract Expressionism.

“Philip Guston: Laughter in the Dark, Drawings from 1971 & 1975,” at Hauser & Wirth‘s Chelsea gallery, brings these works together for the first time, in an assembly so rousingly disrespectful it recalls an outbreak of Tourette’s Syndrome. It features some 180 Nixon satires, three spectacular Tricky Dick-inspired canvases, and over 100 never-before-seen drawings in a sustained outpouring of hilariously smutty caricature.

Organized just weeks before the presidential election by the artist’s daughter Musa Mayer along with Sally Radic, who is currently at work on a catalogue raisonné for the Guston Foundation, the show is on view until after the inauguration. It demonstrates two crucial things: first, that four-decade-old-art can acquire special relevance at unique historical junctures. Second, that Guston’s mature impulse to paint as if “life and art have a mutual contempt and necessity for each other” can—despite our own sustained affair with formulaic abstraction and easy money—reach across generations and connect with people (artists included) on a similarly derisive wavelength.

Philip Guston, Untitled (1971). © The Estate of Philip Guston. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth

What Guston didn’t know before he drew his first Nixon lampoon is that great satire has a funny way of outstripping its author’s intentions. Swift wrote all of his sendups using a pseudonym, and Goya didn’t publish “The Disasters of War” during his lifetime, fearful as he was of the tetchy Spanish Inquisition. In time, Guston came to appreciate the practical consequences of mocking a living president. If Hilton Kramer—in reviewing the painter’s breakout 1971 figurative show in the New York Times—disparaged him as “a mandarin pretending to be a stumblebum,” what would the general press make of his repeated renderings of Nixon’s phallic schnozz and jowls for gonads?

Even after Nixon was disgraced, Guston must have figured that calling an American president a dickhead had its downsides. To understand the artist’s hesitation, consider that a mere twelve years after his resignation, a Gallup poll ranked Nixon among the world’s ten most admired men, and by the time Nixon died in 1994, his reputation was considerably rehabilitated. To borrow a phrase from Orwell’s Animal Farm: “And the creatures outside looked from pig to man, and from man to pig, and from pig to man again; but already, it was impossible to say which was which.”

Among the greatest examples of what Robert Storr has called “the acute discrepancy [Guston] felt existed between the transcendental qualities of his abstract work and the harsh, down-to-earth realities of America in crisis, and his need to confront that strife head on,” these Nixon drawings make up a darkly funny, splenetic but orderly narrative. It begins with a young Richard Milhous at home, dreaming of greatness, among his books and sports pennants, and ends after Nixon’s visit to China, when the suite’s antihero is represented as a penis-shaped cookie. Guston’s bawdy prediction comes straight from the Erotic Bakery—the best is yet to cum.

Philip Guston Untitled (Poor Richard) (1971). © The Estate of Philip Guston. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

Other drawings in this rake’s progress depict Nixon in his legendarily humble childhood home in California (next to literal train tracks); with his dog (or beard) Checkers, which he famously used to dodge accusations of financial improprieties; squeezed into a television set and lifting a moralizing finger; courting the so-called “silent majority” (a term he popularized); devoured by the Chinese dragon (unwittingly); and frolicking at his Key Biscayne retreat with his favorite cronies, Vice-President Spiro Agnew (represented by a thick conehead), Attorney General John Mitchell (a spaniel with a pipe) and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger (a pair of thick glasses).

One additional drawing that did not make the book but that jazzes the show to shockingly indecent heights features a pile-up of Nixoniana. A palm tree, a Billy Graham bible, and pair of elderly voters on television share shallow space with Nixon’s nose probing a pair of buttocks. The latter are emblazoned with the letters “U.S.A.”

Suffice it to say that Guston found in Nixon the perfect embodiment of world-historical perfidy, and in satire a way out of his hopelessness regarding the corrupt state of art and politics. Guston’s Nixon drawings, alternately, can serve as similar inspiration today. This is art used as a scalpel while the world is on a knife’s edge.