It’s been more than 70 years since Jean Dubuffet introduced the idea of Art Brut, and the art world is still learning to embrace the genre of art made outside of more industry-approved avenues of production. Now, there’s another evolution of the genus to consider: Photo Brut.

So posits a new exhibition at the American Folk Art Museum in New York. The largest survey ever to consider photographic art emerging from outside the mainstream art world—and often outside society itself—it may be the best photo show you see all year.

“Photo Brut,” as the exhibition is titled, brings together some 400 works culled from the unparalleled collection of French filmmaker Bruno Decharme, as well as the museum’s own holdings. In includes works by 40 artists, many unknown, who found in photography a space to reconstruct their lived realities into new worlds. (A larger version of the show was staged at the Rencontres d’Arles summer photo festival in 2019.)

In defining the genre, curator Valérie Rousseau, who co-organized the show, recalls the words of art historian Michel Thévoz, who previously oversaw the Dubuffet-founded Collection de l’Art Brut in Lausanne: These artists “use the camera to play against type, by making their daily life an unreality or making their chimeras hyperreal,” Thévoz once said. “They use photography in spite of or beyond its presumptive objectivity, to imbue fantasy with the stamp of realism or, inversely, to sublimate an ordinary subject.”

For these artists, Rousseau explains, “art making and the way they are living on a daily basis is fused; art is not a separate activity.”

Morton Bartlett, Untitled (Girl Reading) (2006). (Original c. 1955.) Photo courtesy of the Bartlett Project, LLC. © The Bartlett Project, LLC.

The work of Morton Bartlett, one of the best known artists in the exhibition, is a helpful entry to the subject. From 1936 to ’63, Bartlett meticulously fabricated a series of lifelike plaster dolls, all styled as young girls and boys, and photographed them in tableaux alternately sweet and sexual, pure and prurient—in a way that recalls Balthus’s Thérèse paintings.

A freelance photographer and graphic designer by trade, Bartlett was clearly aware of the camera’s capacity for world creation. His work was undeniably artistic in its craft and concept, but whether or not it was intended for an audience beyond himself is unclear. His biography also invites a psychological reading of the work: He was adopted at the age of eight after both of his parents died.

Similar points could be made for nearly all of the artists in the show. They operated from a place of marginality, made work with little intention to show it, and, with few exceptions, experienced a great deal of trauma in their life. (The show, to its credit, focuses less on this latter point than does its catalogue, which was produced for the 2019 exhibition in Arles and never passes up the opportunity to mention possessive parents, abandonment, developmental disabilities, or homelessness.)

Many turned to the camera to capture performance, transformation, or role play. Czech artist Lubos Plny, whose work was included in the 57th Venice Biennale, used it to document extreme physical acts, such as sewing his head to his arm. Meanwhile, Japanese artist Ichiwo Sugino, now in his mid-50s, uses tape, markers, and other crude tools to mold his face to look like famous figures—Keith Haring, Jack Nicholson, Louis Armstrong—then photographs the results for his Instagram. The ingenuity on display in Sugino’s pictures is remarkable. He currently has just over 1,000 followers.

Miroslav Tichý, Untitled (between 1960 and 1995). Courtesy of AFAM.

These two artists have found an outlet for their creations, but the same can’t be said for many of the artists in the show. Czech artist Miroslav Tichy, for instance, who made his own low-quality cameras to surreptitiously photograph women in public places, resisted showing his work even as curators took a liking to it late in his life. He lived on the streets while his apartment sat packed with prints, most degraded to the point of abstraction—an apt complement to his lascivious gaze.

Tichy’s work, and other examples in the show like it, raises the question, should we be looking at this art? Rousseau, for her part, has a positive take on the subject.

“When I see these works in isolation, it can be raw or tough or crude; it can be a painful experience. But also I see a transformation,” she says. “I see a way that they have shaped their own trauma while building a reality that is absolutely positive and absolutely constructive. Everybody can look to these examples as inspirations, as… a desire to connect with people that are real around them.”

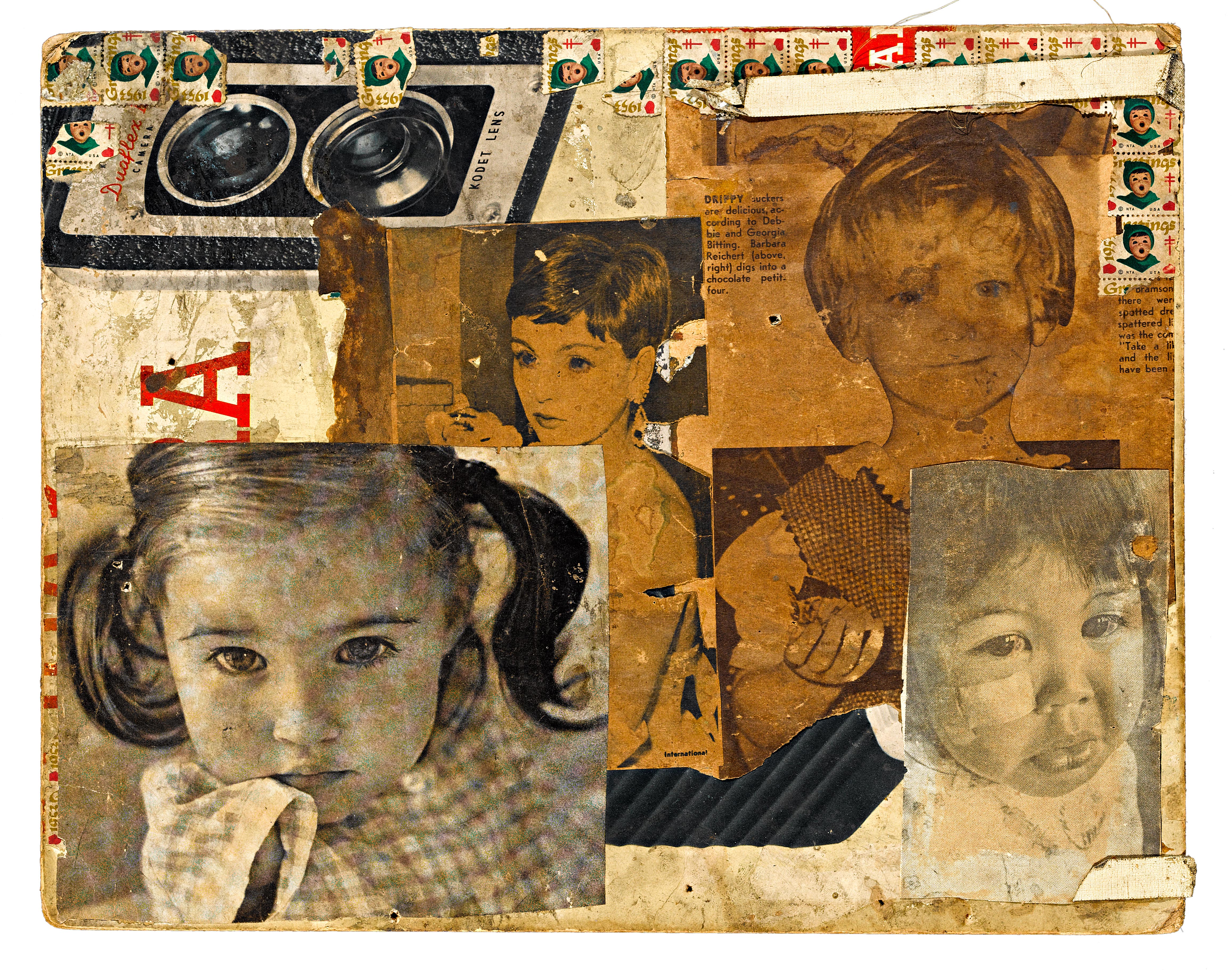

Artist unidentified, known as Zorro, Untitled (c. 1940). Courtesy of AFAM.

“Photo Brut” is on view through June 6, 2021 at the American Folk Art Museum in New York.