“A path along the floor, of proportions 1×21 units, photographed. Photographs printed to actual size of objects and prints attached to floor so that images are perfectly congruent with their objects.”

So read a set of simple, if ambiguous, instructions that Victor Burgin wrote on a single index card in 1967. When followed, the prompt yields a line of photographs that are exactingly printed to mimic the floor on which they’re installed—so much so, in fact, that it’s easy to miss them altogether.

This was Photopath (1967-69), an era-defining work of mid-century photo-conceptualism that still mystifies today, even if—or, indeed, because—it leaves its viewers with more questions than answers. Photopath is the subject of both a new book and a show. The latter, a dedicated exhibition at Cristin Tierney Gallery that opens today, marks the first time in more than 50 years that the influential artwork will be installed in New York.

Victor Burgin, typed instruction for Photopath, 1967. Courtesy of the artist and Cristin Tierney Gallery, New York.

Burgin, now 81, wasn’t a photographer when he created Photopath 56 years ago. He didn’t own, or even really know how to use, a camera. What the technology represented to him was a means to an end—or, more accurately, the “solution to a problem,” he said in a recent interview.

The British-born artist was getting his graduate degree at Yale in the late ‘60s and was hyper-conscious, as many young artists are, of his place in the iterative evolution of artistic ideas and movements—that process where a generation of makers responds to the one that preceded it, and in doing so, establishes a new set of issues for the successive generation to take up.

“We felt, back then, that our generation had to find the problem. Once you found the problem, then you knew what your artistic problem was; it was solving that,” Burgin said.

On the artist’s mind were the slightly older mid-century minimalists—Donald Judd, Carl Andre, and his then-teacher at Yale, Robert Morris—whose formally rigorous work often resisted close examination and instead gestured outward, to the spaces in which it was installed. But Burgin was after something more elusive, something even non-material.

“It struck me then that maybe I found the problem,” he said, recalling it in the form of a question: “What could I do in a gallery that would not add anything significant to the space yet would direct the viewer’s attention to [their] being there?” It was into this context that Photopath was born.

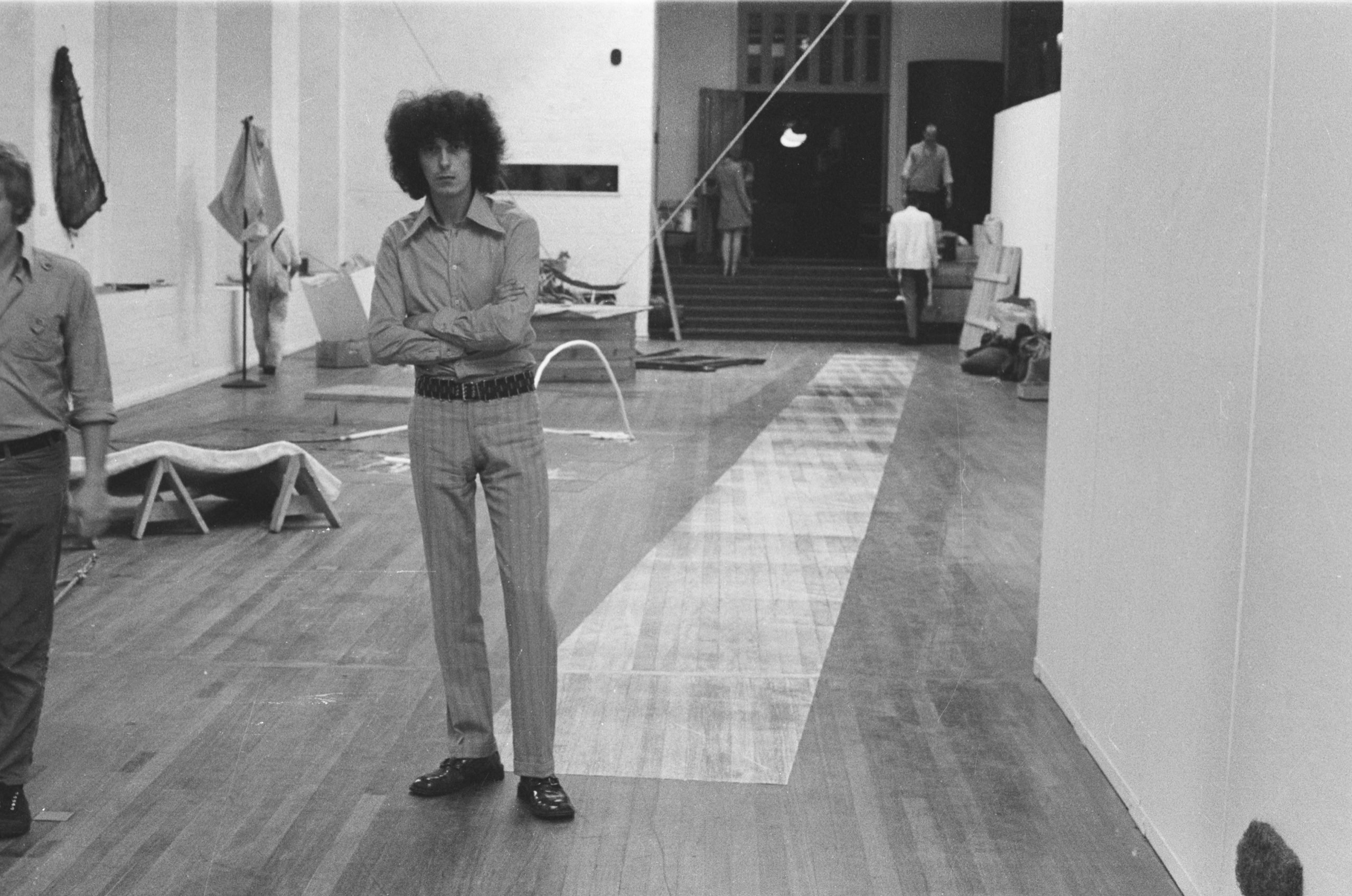

Victor Burgin, Photopath (1967-69), installation view, Nottingham, 1967. Courtesy of the artist and Cristin Tierney Gallery, New York.

The artwork was one of several index cards that Burgin wrote after he had returned to the U.K. Creating instructions for hypothetical artworks satisfied his desire “to do away with the object” in his work, but the cards, too, felt unfulfilled; he needed to enact the prompts to complete them.

So he did. Photopath was first realized on the scarred wooden floor of a friend’s apartment in Nottingham in 1967, then again at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London in 1969 and at the Guggenheim in 1971.

Though the piece was conceived as a kind of sculpture—or an anti-sculpture, perhaps—its impact, in retrospect, feels emphatically photographic. Like few artworks before it, Photopath exploited the medium’s uncanny ability to nestle in between image and object, illusion and idea. If the artwork doesn’t compel its viewers to consider these ideas intellectually, it at least makes one feel them through interaction. Do you treat it like a sculpture or a picture? Or is it not an artwork at all and instead just another stretch of floor? Do you step on Photopath’s prints or walk around them?

“It is hard to imagine an act of photography more straightforward and uncompromising than Photopath,” writer and curator David Campany explained in his recent book on the artwork and its legacy, published last October by MACK.

“It aims to fulfill the basic potential of the medium, which is to copy and to put itself forward as a stand-in or substitute. Yet,” Campany went on, “in meeting this expectation so literally, it somehow estranges itself.”

Victor Burgin with Francette Pacteau photographing the brick floor at Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge, 1984. © Andrew Nairne / Kettle’s Yard, University of Cambridge. Courtesy of Victor Burgin and Cristin Tierney Gallery, New York.

To date, Photopath has only been installed a handful of times, the most recent instance of which came in 2012 at the Art Institute of Chicago’s “Light Years: Conceptual Art and the Photograph, 1964-1977” exhibition, when it was laid upon the polished wood boards of the museum’s Renzo Piano-designed atrium. After the run of the show, Burgin’s prints were discarded, leaving a dark, ghostly silhouette on the sun-soaked floor. He had, in a sense, created another type of photograph.

“I thought, ‘That’s just perfect.’ It really returns [the artwork] to the origin of photography,” Burgin said, noting that the show felt like a fitting conclusion for the artwork. He thought that would be the final time Photopath would be shown.

But that changed last year when Campany approached the artist with the idea of writing his short book about the artwork—a piece of writing that blends analytic art theory and personal experience, often to lyrical effect. What Campany identified in Burgin’s artwork was a kind of foresight for how photographic technology is used today.

David Campany, Victor Burgin’s Photopath, 2022. Courtesy of MACK.

“[J]ust as Vermeer had pursued an important technical development in the picturing of three-dimensional space, so too had Burgin anticipated aspects of representation that are just as pervasive: the replication of surfaces, and the uncertain space between images and their mental impressions. Fake leaves on plastic plants. Laminated tabletops imitating stone or wood. Synthetic clothing pretending to be denim or leather.”

“Photographic ‘skins’ are everywhere in contemporary life,” Campany concluded. “They are not pictures, at least not in the conventional sense, but are a fact of our contemporary material, visual, and virtual experience.”

“Victor Burgin: Photopath” is on view now through March 4, 2023 at Cristin Tierney Gallery in New York. Victor Burgin’s Photopath by David Campany is available now through MACK.