A fragment of rock-and-roll history—parts of the stairs leading to Jimi Hendrix’s apartment in London’s Mayfair—have been acquired by the Detroit Institute of Arts. They were salvaged and transformed into a work of art called There must be some kind of way outta here (2016), by the British artist Cornelia Parker.

Parker’s riff on Hendrix heritage comes with a backstory. She retrieved the parts of his staircase when she heard they were in danger of being dumped during the transformation of the Handel House Museum in London into a Handel and Hendrix experience. The American musician lived in the flat at 23 Brook Street from 1968-69. It is next door to the home occupied by the German-born composer George Frideric Handel 200 years earlier; they have been a combined attraction since February 2016.

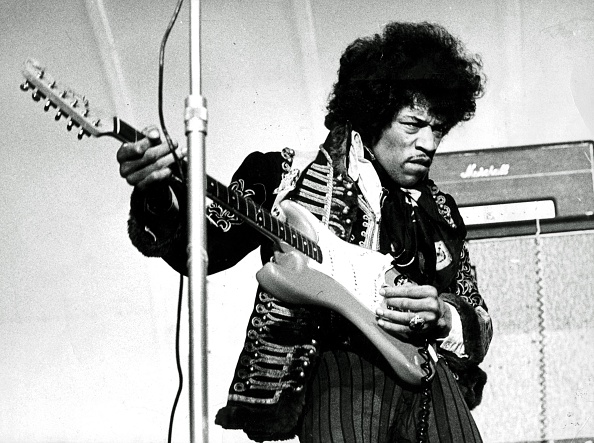

Cornelia Parker’s There must be some kind of way outta here (2016), courtesy of Frith Street Gallery

Laurie Farrell, the curator of contemporary art at the museum, told artnet News: “We are working on reinstalling our entire contemporary art (post-1950) collection for December 2020. As we work towards this reinstallation we’re making strategic acquisitions to build on our collection strengths.” She adds that Hendrix played in Detroit many times. Hendrix’s live album at Cobo Arena in 1969 is highly sought after by music collectors, she says. “Since music is so important for Detroit we feel this work will resonate deeply with a broad audience.”

There must be some kind of way outta here, which Farrell and a group of DIA patrons spotted on Frith Street Gallery’s stand at Frieze London in October, was first shown in the exhibition “Found,” which Parker curated at London’s Foundling Museum in 2016. She installed works by around 50 contemporary artists, including Christian Marclay, Gavin Turk, and Mike Nelson, among others, within the collection of the museum that tells the story of a foundling hospital created in the early 18th century by Thomas Coram, a former sea captain. The orphanage had an illustrious list of benefactors from the start, including Handel, the British artist William Hogarth, and King George III.

The Detroit institution announced this week that Parker’s work is due to go on show in a new gallery called “Out of the Crate,” which is slated to open on January 12. It will be joined by seven other acquisitions, two of which are gifts, the rest purchases like Parker’s work. They include an African 19th-century sculpture Maternity Figure (Obaa Hemaa); a sculpture of Saint Benedict of Palermo (1770–80), attributed to Juan Pascual de Mena; Hiroshi Sugimoto’s silver-gelatin print Fox, Michigan (1980); and James Abbott McNeill Whistler’s etching Salute Dawn (1879).

In a statement, the museum’s director Salvador Salort-Pons says: “This gallery offers a transparent look at the DIA’s collecting process and policies while giving visitors a first look at both recent purchases and gifts.” The display is due to be rotated regularly. It is a far cry from the situation that the museum faced after Detroit filed for bankruptcy protection in 2013. The museum and its supporters had to fight off a possible forced sale of historic works purchased with funds from the city.