It’s difficult, if not impossible, to document dance secondhand, but a retrospective of the visionary modern dancer Pina Bausch at the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin gives it a fair shot.”Pina Bausch und das Tanztheater” is a view into the archives of the late dancer, who founded the Tanztheater Wuppertal, and directed and choreographed there from 1973 until her death in 2009.

Divided into four sections—“the dancer,” “the methodology,” “the stage,” “the coproductions,” and “the ensemble”—the retrospective comprises video footage, photographs, and ephemera. Plus, a reconstruction of “Lichtburg,” Bausch’s practice space in an old Wuppertal cinema, and during the exhibition, a series of workshops, public rehearsals, film screenings, performative interventions, and talks take place inside. Despite a lack of context from the exhibition-maker’s side, the show provides a rare glimpse into the dancer’s life’s work.

Bausch’s life’s chronology is organized in the ground level of the Martin-Gropius-Bau’s cavernous Neo-Renaissance exhibition space. Around the perimeter of the square room, viewers follow the dancer’s genesis from a student of classical ballet, to an experimental choreographer with a unique, avant-garde vision. A lack of informational wall texts throughout the exhibition, however, leave an unfamiliar viewer to piece together much of her life on their own.

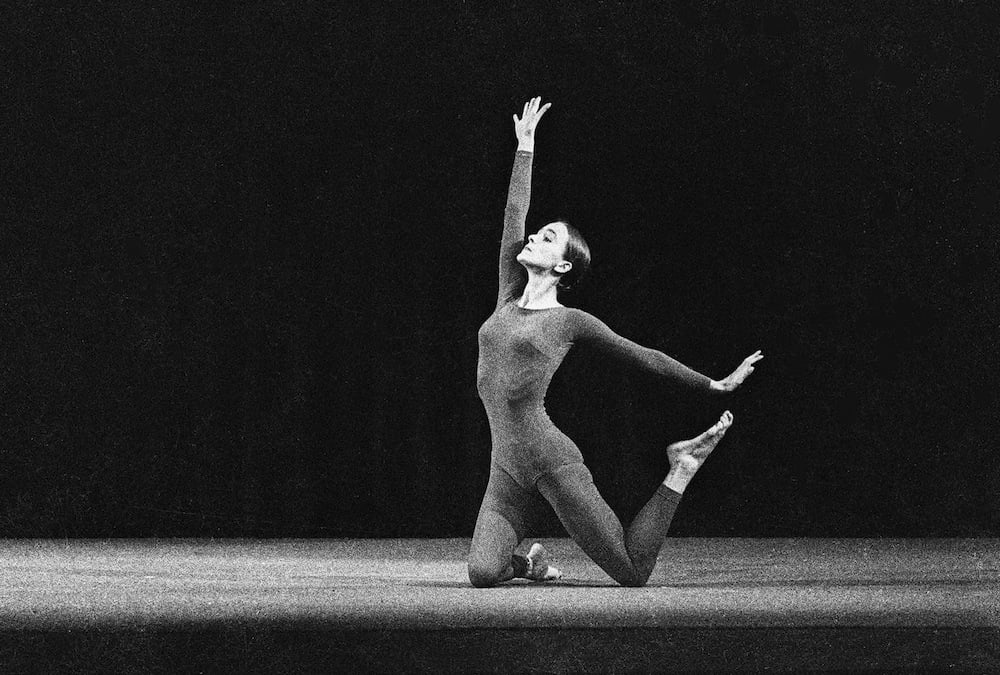

Rehearsal: A Choreographer Comments, Choreography by Antony Tudor, Juilliard School, New York, 1960. Photographer unknown, courtesy Pina Bausch Foundation, Juilliard Archives.

Born in 1940, at age 15 she began to study under Kurt Jooss at the Folkwangshule in Essen, before moving to New York in 1958 to study at Juilliard. Photos of the young, classically beautiful Bausch are brought to life with archival video clips of her dance classes—typical scenes of identical young, thin women wearing black leotards and slick buns, dipping on barres.

But Jooss was a rulebreaker in his own right, and a key figure in the history of Tanztheater style. It is expressionistic, uniquely German, and uses choreography to tell dramatic stories. A clip of Bausch dancing the character of the old woman in Jooss’ seminal The Green Table especially stands out among the hours of archival reels. In the ballet, a reflection on European war violence preceding the rise of the Nazi party, Bausch is part of a “refugee” ensemble. She is eventually taken by the figure of death, in a hauntingly beautiful dance.

Pina Bausch and Dan Wagoner in Tablet (1960), Spoleto, Italy. Choreography by Paul Taylor. Costumes by Ellsworth Kelly. Photo courtesy Pina Bausch Foundation.

By the 1970s, Bausch’s own creative point of view had taken shape. One vitrine shows a collection of handwritten notes, sketches, and programs for her 1971 Aktionen für Tänzer, one of her first works with the Wuppertal theater. The piece is reminiscent of Fluxus event scores (perhaps not by coincidence, the city of Wuppertal hosted some key early Fluxus happenings). Photographs of the piece show a performer lying in a clinical-looking bed while an ensemble moved around and on it—a far cry from orderly exercises undertaken by young ballerinas.

When she began directing at Wuppertal, Bausch shifted her energy from dance to choreography. The second half of the exhibition, staged in a series of white-walled side rooms, focuses on the Tanztheater and her work as a director.

A performance photo of Pina Bausch’s The Rite of Spring. Photo by Zerrin Aydin-Herwegh.

The introductory “The Methodology” section illuminates Bausch’s unconventional way of working collaboratively with her dancers, whose individual personalities she wanted to let shine on the stage. To get to know them, she would ask questions and assign tasks. The result of one of these tasks, “Draw a tree,” is the first thing the viewer sees when entering this room: a set of drawn responses on printer paper ranging from 2-D childlike renderings, to more sophisticated, shaded, nature studies, to the Chinese character for “tree.”

This room also contains a trio of video screens, each playing an overwhelming loop of clips from Bausch’s pieces. The sartorial trends of the 70s and 80s date the clips, like one from 1979’s Keuschheitslegende (Legend of Chastity). Men and women in tuxedos and jewel-toned cocktail dresses sit in a half-circle of cushiony furniture, making small, repetitive, localized movements. One dancer aggressively rolls his shoulder, another compulsively tucks her hair behind her ear, while one pokes her twitching tongue out of her mouth. The clip reveals Bausch’s exploratory, and not always comfortable, interest in movement.

A performance of Pina Bausch’s Vollmond (Full Moon), Wuppertal, May 2006. Photo by Laurent Philippe.

Adjacent rooms focus on Bausch’s stage designs, which she developed with her partner Rolf Borzik until his death in 1980. Spatially economic yet strewn with obstacles, sets often referenced everyday life with props like modest wooden chairs, or incorporated natural elements like leaves, soil, and water. “Vollmond,” a memorable mature piece from 2006 documented here in large, glossy, color photographs, required 8,000 liters of water for dancers to emphatically splash and throw.

“The Coproductions” documents, complete with personal travel photos scattered beneath glass tabletops, Bausch and co.’s excursions abroad to develop pieces inspired by foreign cultures and people. This began with the composition of “Viktor” in 1986 with the Teatro Argentino in Rome, and in the subsequent 21 years the Tanztheater collaborated with theaters in Palermo, Madrid, Vienna, Los Angeles, Hong Kong, Lisbon, Budapest, Sāo Paolo, Istanbul, Seoul, and New Delhi.

Rehearsal for Er nimmt sie an der Hand und führt sie in das Schloß, die anderen folgen, Bochum, 1978. Photo by Ulli Weiss, courtesy Pina Bausch Foundation.

And not to leave out the most integral part of the theater, the final section, “The Ensemble,” credits the dancers with whom Bausch worked. As the director would have wanted, a wall of individualistic portraits captures members of the Tanztheater past and present.

In a screening room beyond, projections of three different pieces play simultaneously. Another example of the excess of materials hiding away in the Pina Bausch Archives, it leaves the visitor with the feeling that Bausch’s vast output and legacy requires an even more monumental exhibition.

“Pina Bausch and the Tanztheater” is on view at the Martin-Gropius-Bau until January 9, 2017.