As the saying goes, it’s the victors who write the story. But in the case of Documenta, Germany’s world-famous art exhibition founded in the rubble of World War II, the opposite is also true.

“Documenta: Politics and Art,” a major new exhibition at the German Historical Museum in Berlin, explores the political powers that influenced the trailblazing show from its inception.

The exhibition examines the first 10 Documentas, charting their sometimes troubled underpinnings, their organizers, the artists they showed (and didn’t), and the financial dealings that engineered each show, diving into how art became a critical chess piece in Cold War politics and a tool to engineer Germany’s selfhood after the war.

Documenta, it’s clear, was far from just a neutral celebration of contemporary art.

Guerrilla Girls, Why in 1987 is Documenta 95% white and 83% male? from 1987 made around Documenta 8, 1987 © Courtesy of Guerrilla Girls, www.guerrillagirls. com

The Continuity of Nazi Influence

A look at Documenta’s origin story offers startling revelations.

The show had a fledgling start in Kassel in 1955, which was still in ruin after the war. The small city was an ideal location, not because it was a bustling art hub from prewar times, but rather because it was close the East German border. Establishing a star-powered art show that championed Western art and ideals was of clear political value, perhaps especially when the East-West border was still somewhat permeable.

“You can’t make culture with politics, but maybe you can make politics with culture,” former West German president Theodor Heuss said in the years preceding the show’s establishment.

Unwittingly, Heuss’s words signal to darker truths about the show. What art was championed, and what was left out? Women and artists of color were largely excluded until about a decade ago. What’s more, recent research reveals that 10 of its 31 original organizers were either Nazi party members, in the SS, or the SA, Hitler’s original paramilitary wing. The second show involved six former Nazis; the third, 15.

Painting Horizon (1970) by East German painter Wolfgang Mattheuer, which was included in documenta 6. Copyright: bpk / Nationalgalerie, SMB

The presence of former National Socialists in positions of power had definitive and sometimes disturbing effects on what art was shown.

One part of the exhibition looks at Documenta co-founder Werner Haftmann, a Nazi party member who obfuscated his history after the war. In Italy, he was a wanted war criminal, known to have hunted, tortured, and executed resistance party members. As a Documenta founder, he was involved in its first three editions, between 1955 and 1964.

Arnold Bode, the show’s cofounder, “was likely aware of being surrounded by Nazis, but Haftmann kept his past a secret,” Julia Voss, one of the Berlin show’s co-curators, told Artnet News. He excluded artists from the exhibition who may have spoken about or experienced the Holocaust, and Jewish artists that were included in early editions largely lived in exile.

Among the works in the show are a still life of flowers and a self-portrait by the German Jewish painter Rudolph Levy, who lived in Florence during the war. By chance, Haftmann, who was stationed in the city at the time, held an office one floor below Levy.

It’s possible they would have been aware of each other: in a letter written around the time of the inaugural Documenta, Haftmann asked if “Levy is still alive in Florence.” But Levy, who was arrested in December 1943 and died on the way to Auschwitz, was not included in the show. Nor was another German Jewish artist, Otto Freundlich, who was also murdered by the Nazis. A preparatory document shows his name proposed, and then crossed out.

In the Berlin show’s catalogue, Voss writes that this “was no coincidence: work by Jewish artists who, like Levy, had been murdered by the National Socialists, was not on show at all in Kassel in 1955.”

Co-founders of Documenta Werner Haftmann (left) and Arnold Bode at the opening ceremony of Documenta 3, 1964. Documenta archiv © Wolfgang Haut, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung

MoMA, the Cold War, and the C.I.A.

Two other major sections of the show look at the Americanization of Documenta, which was closely tied to political events in East Germany.

In 1959, Documenta 2 included 37 American artists in an “institutional package” put together by MoMA director Porter MCCray; not a single work he chose was figurative. Instead, Documenta that year championed Jackson Pollock and East German artists who worked in an Abstract Expressionist style, rather than the figurative work that was prevalent in the country at the time. Documenta 4 followed a similar pattern, with artists like Andy Warhol and Jo Baer heralding Pop Art and Minimalism.

“Documenta was part of a geopolitical battle and a cultural battle as well, and the exhibition and its organizers were involved in creating certain constructions about both the East and the West,” Lars Bang Larsen, the Berlin show’s co-curator, said.

MoMA’s possible ties to the C.I.A. have long been a subject of speculation, and although little has been definitively proven, research for this show reveals that Documenta 3 organizers got a grant from the European Cultural Foundation, which was later revealed to be a funding channel for the C.I.A.

Bang Larsen said the curatorial team tried to access MoMA archives that have concrete answers about the museum’s connections to the government agency, but the files remain restricted.

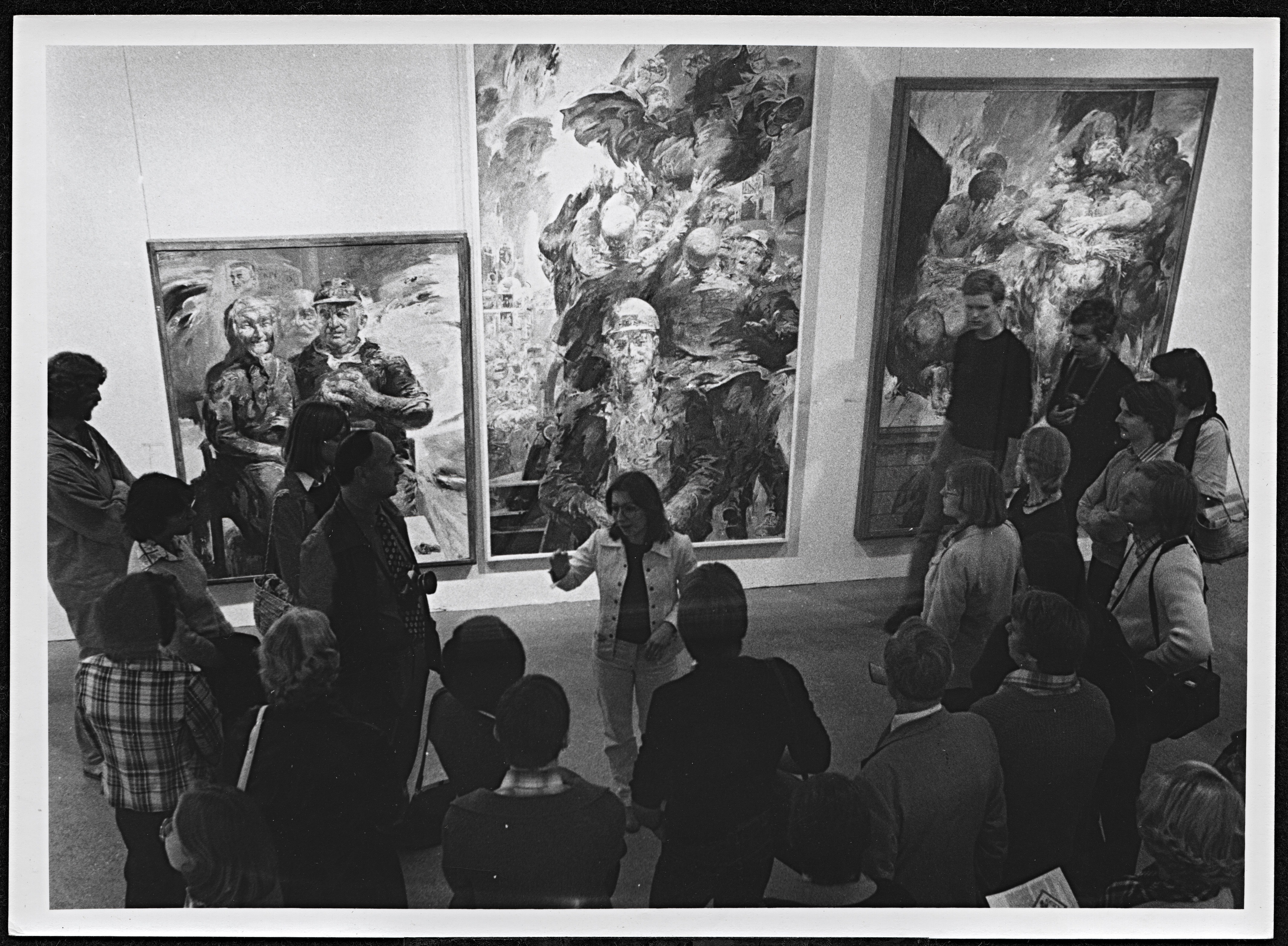

East Germany’s art scene was always involved in the show to varying extents. Former East German artists were shown, though the works and artists selected where highly edited. In Documenta 6 in 1977, a broader array of ideas were presented than in previous editions—namely, direct criticisms and reflections on World War II and the Holocaust.

The most powerful example of this came from U.S. artist Beryl Korot, who showed a multichannel video of tourists walking away from the former Dachau concentration camp.

Meanwhile, East German artist Werner Tübke’s Reminiscences of Judge Schulze III, a large painting with vivid, Hieronymus Bosch-like details depicted a Nazi judge on trial against a landscape of death and torture.

But not everyone was pleased with all the changes: German artist Georg Baselitz withdrew from the exhibition in protest of the presence of East German artists, whom he felt came from “a place of intolerance.”

Hans Haacke (b. 1936), Hommage à Marcel Broodthaers Documenta 7, 1982 © Documenta archiv, photo: Udo Reuschling / © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021

The German Historical Museum show ends after Documenta 10, when the now-deputy director of the Pompidou, Catherine David, became the first woman to curate the show and reorient it away from its East-West axis towards broader global issues.

In 2022, the Indonesian collective ruangrupa is leading the charge, organizing the show around the concept of lumbung, a term referring to an Indonesian communal rice barn. Their show plans to embrace resource-sharing and community-based networks.

The show, no doubt, looks different than it did before. But its stature in the art world has only grown. As bang Larsen put it: “there’s no tradition quite like it.”