Archaeologists have found new inscriptions in a house in Pompeii inviting voters to elect a man named Aulus Rustius Verus to office. The discovery was made in the Regio IX area, where elaborate food-themed frescos were discovered in another home earlier this year.

The findings were published September 28 in Pompeii Scavi, the online scientific journal of the Pompeii Archaeological Park.

“I beseech you to make Aulus Rustius a true aedile, worthy of the state,” reads part of the inscription as translated from Latin. The Latin text was deciphered despite missing letters and abbreviations.

Verus was running for the office of aedile, an elected office in the Roman Empire who had powers to maintain public buildings and infrastructure, regulate public festivals and enforce public order.

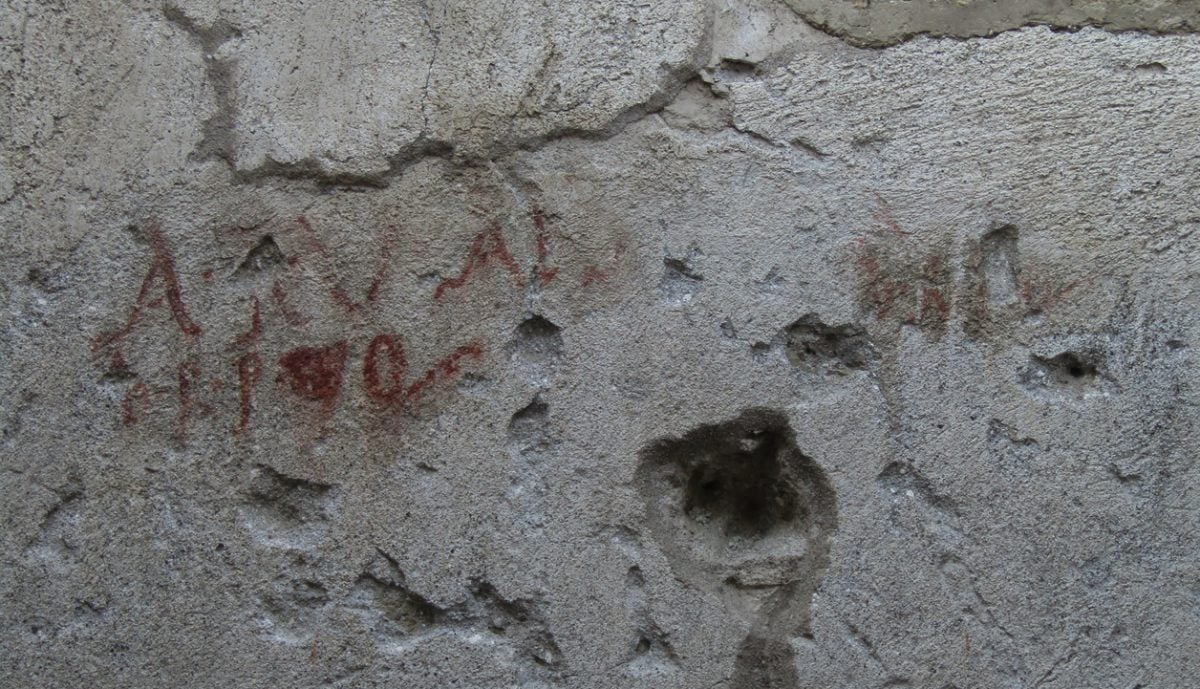

An inscription is seen on the south wall lararium, a shrine to the guardian spirits of the Roman household. Photo courtesy of Pompeii Archaeological Park

Archaeologists and historians have already established that Verus would go on to hold the higher office of duumvir—a position he held jointly with a man named Giulio Polibio. Verus’s precise outcome is not known but it’s possible he died when Mount Vesuvius erupted in 79 A.D.

Normally, such political ads were written on the outside of buildings, but the inscriptions were found inside a room containing the lararium, or household shrine. The home believed to have belonged to either a friend or a Verus freedman, a class of former slaves who remained in a socially obligated patronage with their former master.

The researchers suggest that the presence of the inscriptions in the home, which housed a bakery and was going under renovation at the time of the volcanic eruption, shows an example of the campaign practice of organizing events and dinners in the homes of the candidates and their friends.

The presence of the bakery further shows how Verus understood that “the voter lives on bread” and suggested that politicians were engaging in questionably legitimate election practices.

Archaeologists also discovered the final sacrifice made on an altar in the home where the inscription was found. Photo courtesy of Pompeii Archaeological Park

“The electoral passion was lived with intensity in Pompeii: it filled the streets, it warmed soul,” archaeologists wrote in a post on the Pompeii Archaeological Park’s website.

“The electoral programs of Pompeii are a precious source for reconstructing the history of the city, for tracking down the characters who shaped its political events and sketching a first prosopography of the ancient Pompeiians, for giving a name to their supporters, reconstructing their social relations and understanding the reasons for their support for one or the other candidate.”

Archaeologists said that almost all the texts in support of the candidates, essentially electoral posters, are visible along the streets of Pompeii.

More Trending Stories: