A clever new artists’ book highlights the fact that while some serve time for minor offenses, corporate officers whose companies may be guilty of grievous acts tend to walk free. It features renditions of corporate executives from companies like Chevron, Goldman Sachs, and Monsanto, all drawn by people who are serving prison sentences.

Artists Jeff Greenspan and Andrew Tider have published Captured: People in Prison Drawing People Who Should Be; all profits from book sales will go to support the presidential campaign of Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, who has made corporate responsibility a cornerstone of his campaign. (He also has pledged to support the arts if he gets into the Oval Office.) It’s a limited edition of a thousand books; at time of writing, nearly half have sold.

The pair was also responsible for the guerrilla installation of a bust of National Security Agency whistleblower Edward Snowden in a Brooklyn park. That work is included in a current exhibition about activist artists at the Brooklyn Museum.

Jaime Vidales, Former CEO of Dupont, Ellen Kullman.

Photo: courtesy Jeff Greenspan and Andrew Tider.

The book project began when the pair were watching documentaries about environmental crimes, and were outraged that the alleged corporate perpetrators can get away with only monetary consequences.

“If any normal person did these things, they would end up in jail,” said Tider in a phone interview. They imagined staging conversations between people imprisoned for, say, marijuana possession and CEOs of companies guilty of major infractions, but ended up settling on a simpler, punchier way to get their ideas across.

“Andrew and I had spent a lot of time working in advertising, and we’ve learned how to capture people’s feelings and imagination,” said Greenspan. “We realized that we should use some of the skills we’ve learned not only selling products but also selling causes.”

Among the subjects are WalMart CEO C. Douglas McMillon, whose company, according to the artists, is engaged in bribery and tax evasion, among other crimes. McMillon’s benign-seeming face is captured in ballpoint pen and pencil by Charles Lytle, who is serving nine years for robbery and assault.

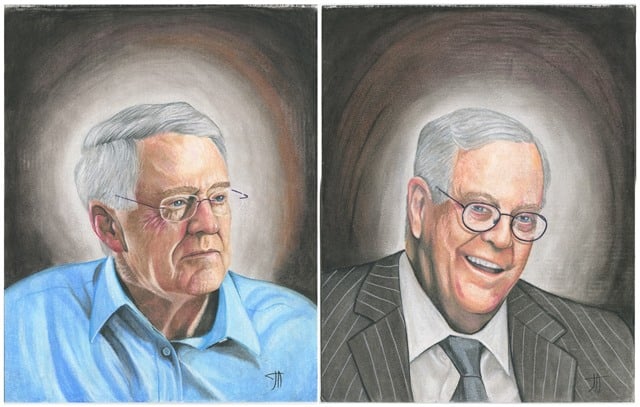

Charles and David Koch appear in portraits drawn by Joseph Acker, who is serving ten years for receiving stolen goods, identity theft, and felony possession of body armor. The Koch brothers, meanwhile, as owners of energy company Koch Industries, have been accused of selling petrochemical equipment to Iran, a state sponsor of terrorism. Ironically, those portraits feature halos around the brothers’ heads.

BP’s former CEO Tony Hayward earns a portrait for having overseen the company behind the Deepwater Horizon oil rig, which spewed millions of barrels of oil into the Gulf of Mexico. He’s drawn by Benjamin Gonzalez Sr., currently doing nine years for robbery.

Other artists have examined the crossover of incarceration and visual art. In a similar vein to Captured, Jeremy Deller’s British pavilion presentation at the 2013 Venice Biennale included drawings by imprisoned Iraq War veterans, some of them depicting architects of the war. For her part, photographer Deana Lawson has documented visits by her cousin to her husband at a New York correctional facility, and photographer Alyse Emdur’s book Prison Landscapes reveals the strange murals before which inmates pose for photos.

Charles LIsto Vera, Chairman of the Nestlé Group, Peter Brabeck-Letmathe.

Photo: courtesy Jeff Greenspan and Andrew Tider.

Greenspan and Tider did concede that there were tough decisions in developing the project. They don’t want to give the impression that they are condoning the inmates’ offenses. They also hesitated to enlist those convicted of violent crime. While they ended up not employing artists imprisoned for rape or of killing police officers, they did use some artists convicted of murder.

“It was a challenge to justify that to ourselves,” Tider said. “But GM is essentially guilty of manslaughter. The company waited ten years to inform people of faulty ignition switches that caused hundreds of deaths. Nestlé works with companies that use child slaves to harvest cocoa. Why shouldn’t we work with inmates guilty of equally awful crimes?”