Artist Prune Nourry didn’t set out to make a film about her battle with breast cancer. When the terrible diagnosis came, at age 31, she was in the middle of documenting an art project she had made about gender selection in China, titled Terracotta Daughters.

But her new documentary, Serendipity, which debuted at the Tribeca Film Festival, was inspired by director Darren Aronofsky—who also co-produced the film—when he told her “as an artist, anything that happens to you, you can turn it into creativity,” she told the audience at Tribeca after the screening.

The film’s title comes from “the relation between intuition and chance,” Nourry said. Years before she was sick, the artist had staged an artistic dinner party titled the Procreative Dinner, in which each course was inspired by the artificial insemination of an embryo—a process that is necessary for women who want to become pregnant after undergoing chemotherapy. Serendipity shows footage from Nourry’s research for that project at a medical facility, as well as her own egg retrieval procedure ahead of chemo.

“Did I know it would come? Did I create the illness?” Nourry wondered to the audience.

Nourry did not like turning the camera on herself. “I hate that, being filmed,” she said. But she kept Aronofsky’s words in mind and decided to explore the connection between what was happening to her at that time and the work she had been making about women and their bodies for years before.

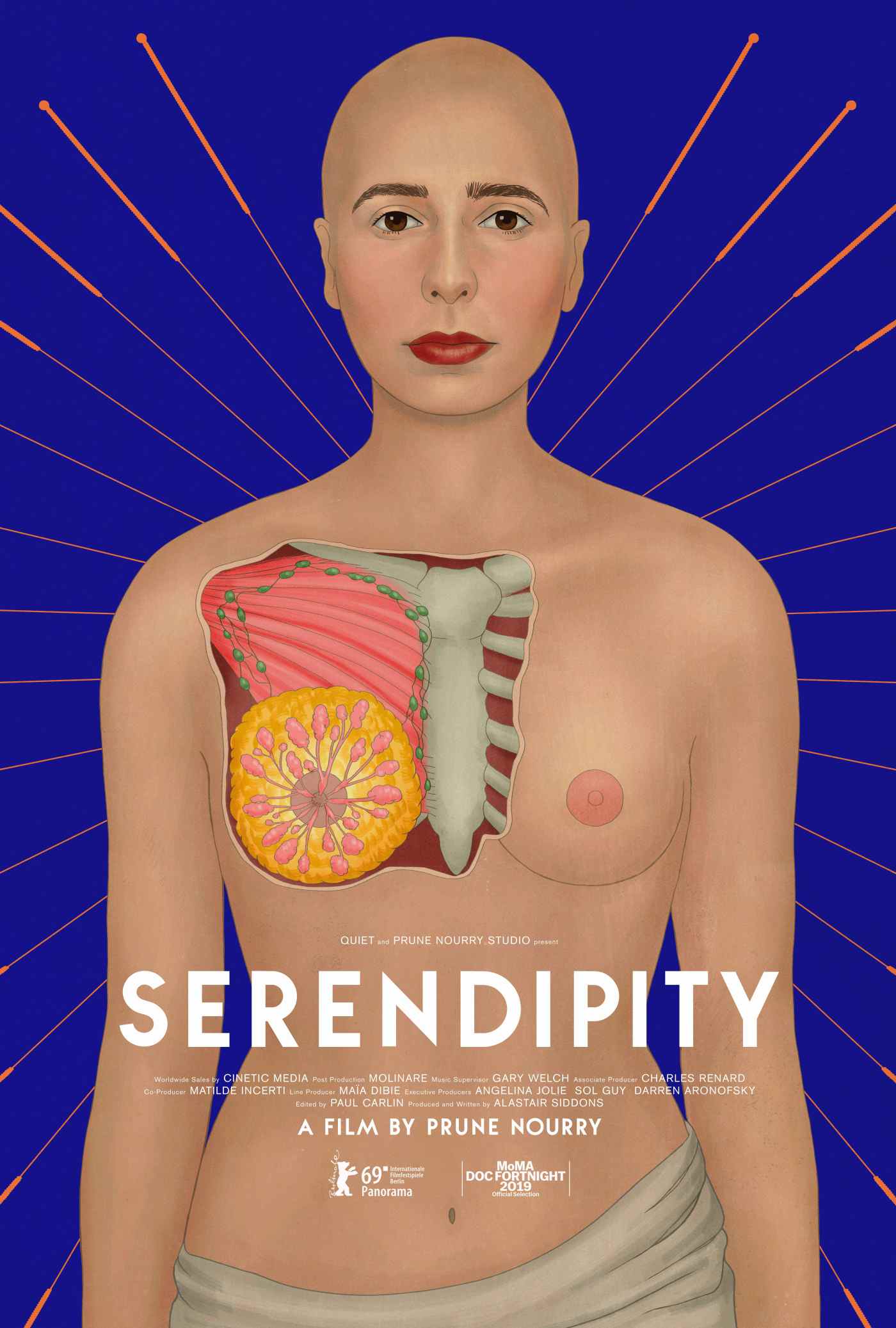

Still from Serendipity, directed by Prune Nourry. Courtesy of the Tribeca Film Festival.

The film, which was co-produced by Angelina Jolie, who underwent a preventative double mastectomy in 2013, follows Nourry through her illness and her journey back to health.

At one point, she plaits her long dark hair into a braid and chops it off, as filmmaker Agnès Varda stands by and offers moral support. Then Nourry shaves her head and arrives at her own gallery opening wearing a surgical mask over carefully applied lipstick. Preparing for reconstructive surgery following her mastectomy, Nourry tells her doctor, who has marked up her butt and thighs with surgical guides, that “today, you’re the sculptor.”

Prune Nourry’s Serendipity. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Through it all, the artist offers an unvarnished look at the day-to-day realities of cancer treatment and its effects on the body. “When you’re ill, you realize health is everything,” Nourry says during the film. “Once you accept doing less, then it’s easier.”

But then, the next shot shows her hard at work, preparing for an ambitious exhibition at the Guimet Museum in Paris. “When you learn the fact that you might die, it reshapes all your priorities,” she says soon after. The most important things are “health and art and love.”

A still from Prune Nourry’s Serendipity. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Somehow, breast cancer seems to have honed Nourry’s artistic edge, giving her clarity of vision and helping her understand what she had been working toward all along. But the movie is not a glorification of illness. Rather, it acknowledges how focusing on her work “was a way to come back to being a sculptor, and not being a sculpture.”