Purdue Pharma, the company behind the prescription drug OxyContin, submitted its bankruptcy restructuring plan this week in a move that, if approved, would transform the business into a new corporation and remove members of the Sackler family from power.

But following the company’s court filing in New York, the attorneys general from 23 states issued a statement calling for amendments to the plan, which they say does not offer sufficient concessions—including one that would protect non-profits that opt to remove the Sackler name from their spaces, regardless of gift agreements.

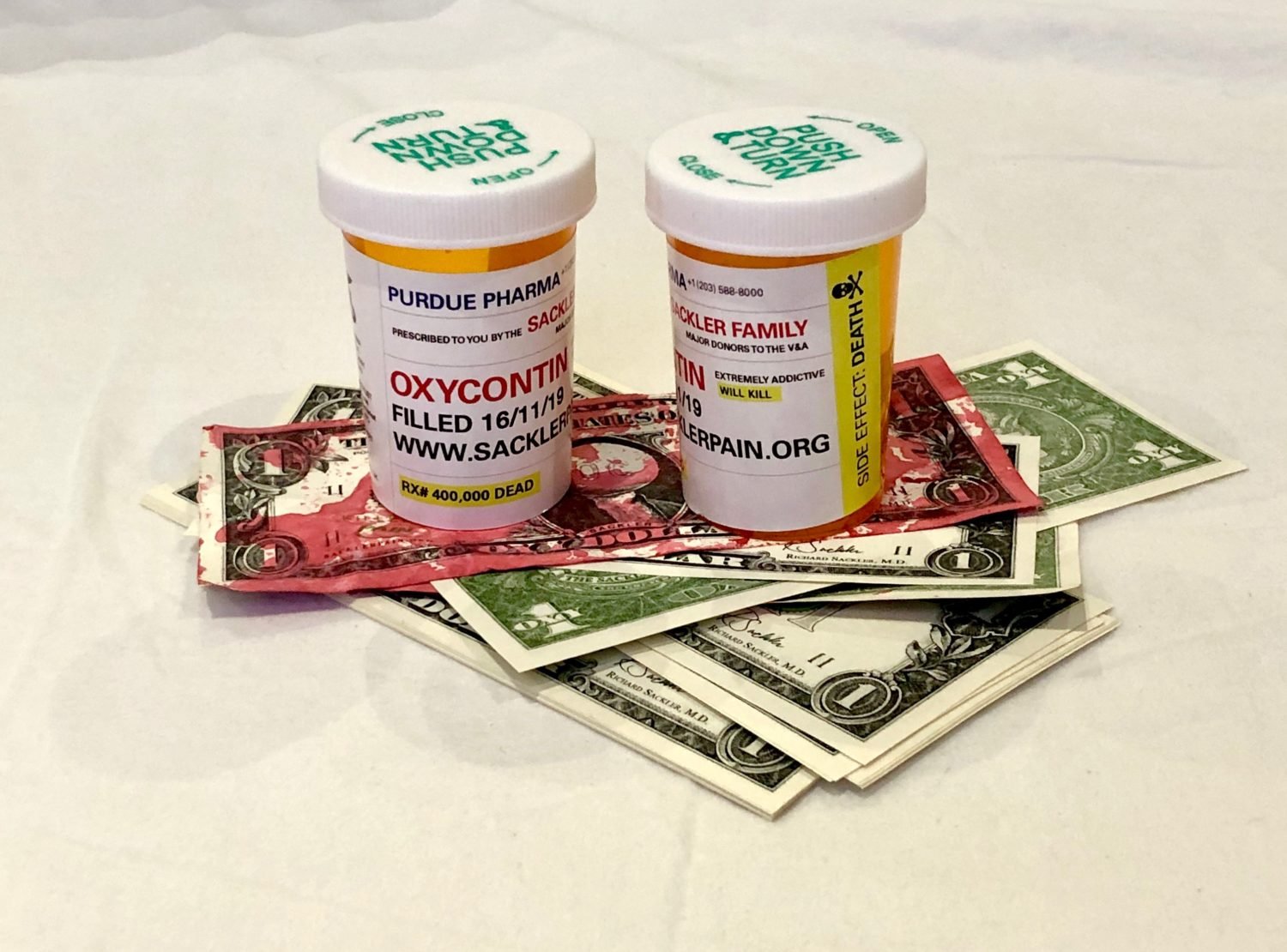

Purdue has pleaded guilty to several felony offenses for its role in the opioid crisis that has taken hundreds of thousands of lives over the past decade.

“We are disappointed in this plan,” the attorneys said in the statement, adding that it “falls short of the accountability that families and survivors deserve.”

For museums and other non-profits, a divorce from the Sackler name is more complicated than simply removing the title from a gallery wall. It could be why we haven’t seen some prominent institutions, like the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which has an entire wing named after the family, do so. (Last fall, a Met representative told Artnet News that the name “is under review.” In 2019, the museum pledged to reject funding from the Sackler family altogether.)

Often, major financial donations of the type the family has become known for come with binding stipulations, including naming rights. Private messages between Sackler members recently made public through lawsuits showed how the family tried to leverage their years of philanthropy to solicit positive PR from museums during the scandal. Now, should the attorneys’ proposed amendments be factored into the restructuring plan, museums could bypass those preconditions without the prospect of repercussions, such as losing the money previously donated by the Sacklers.

“This amendment would free museums from any litigation, and allow institutions to denounce the Sacklers,” said artist Nan Goldin on behalf of P.A.I.N., the activist group she leads that has staged numerous protests against Purdue and members of the Sackler family. “They no longer deserve the cultural legitimacy their naming rights have afforded them. As an artist whose work is in the collections of many of these museums, I expect them to live up to the ethics that I live by.”

More than 300 pages long, the Purdue bankruptcy plan would put control of the company in the hands of independent managers selected by state and local governments, with all profits put toward efforts to fight the opioid crisis. It would also require members of the Sackler family to pay $4.275 billion to the thousands of plaintiffs who have brought lawsuits against the company for costs associated with the epidemic.

This is the second such plan proposed by Purdue. The first, submitted in 2019, was rejected by the legal representatives of the many plaintiffs. Whether or not this iteration will be approved is yet to be seen, but it’s already drawn numerous public opponents in addition to the attorneys general. Many of these voices have objected to the fact that the deal would reportedly shield individual Sackler family members from further lawsuits.

“This proposed settlement is criminal, shielding the Sacklers’ personal wealth while leaving the American public holding the bag,” P.A.I.N. said in a statement after Purdue’s proposal was submitted. “Purdue Pharma’s reorganization plan is proof that billionaires have our legal system on a tight leash. This settlement is entirely on the Sacklers’ terms and is of no benefit to the people and communities they’ve destroyed.”