Hidden details have been discovered in ancient Egyptian paintings using portable chemical imaging technology, researchers said in a new study published in the open journal PLOS One.

The study, which focused on two paintings from the Theban Necropolis near the Nile River that date back more than 3,000 years, marks an advancement for Egyptology and demonstrates how researchers can use such portable technology to study ancient sites.

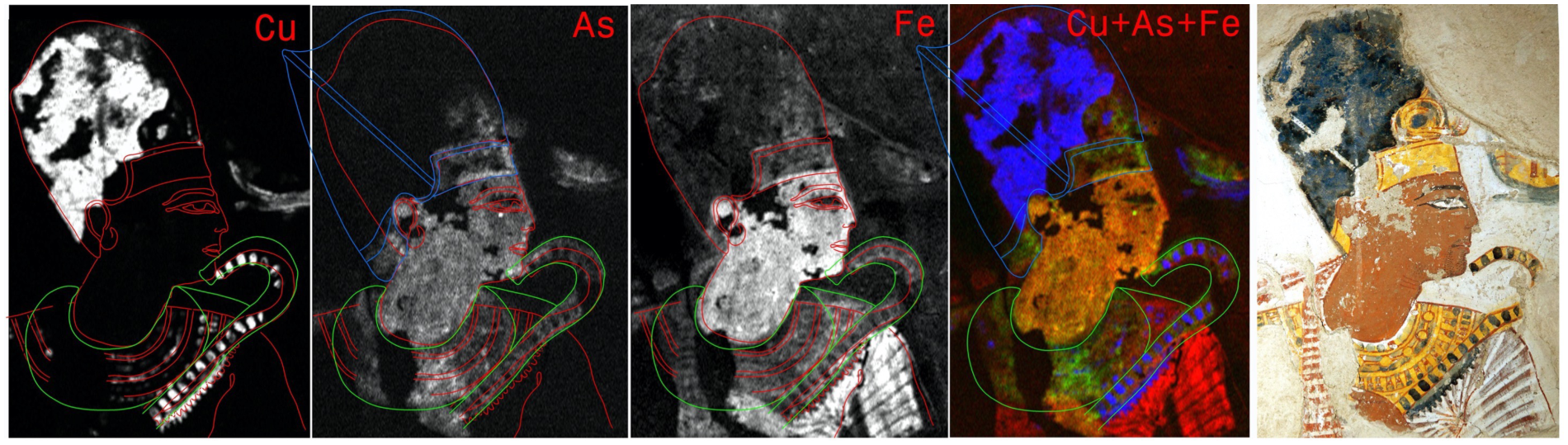

The x-ray fluorescence imaging process allows the researchers to analyze the chemical composition of the paint and how it was layered, providing a look at how the artists made each work.

The researchers noted that other studies have formed theories for the workflow of artists at the time, which have also found that the ancient Egyptians rarely made alterations to their paintings during the process or afterward.

The team said they selected work already known to have alterations in the hope of understanding the reasons for them and how the ancient Egyptians made work by using chemical imaging technology.

The authors are trying to find out “whether there is more to see than what meets the eye,” they wrote.

Previous scientific studies of ancient Egyptian art have focused on pigment samples taken offsite to labs for analysis, which the researchers noted are generally in agreement with archaeological observations.

“XRF-imaging is well suited for the investigation of Egyptian paintings,” the authors, led by Philippe Martinez of Sorbonne University in France, wrote, noting that pigments used by the ancient Egyptians used elements detectable with the technology. For example, calcium, copper and silicone are each detectible with XRF imaging to find the color Egyptian Blue.

The alterations examined by the researchers include a hidden third arm for a scene in which the ancient Egyptian official Menna and his wife are pictured admiring Osiris. The alteration has been known since the discovery of the painted tomb chapel of Menna in 1888 because it is visible to the naked eye.

The team did discover adjustments to the crown and other royal items on a portrait of Ramesses II from a previous, unseen version of the portrait.

“The significant retouching of the royal figure and its own dating remain very difficult to determine and to understand,” the study reads.

“We are in this case very far from the correction visible in the tomb of Menna, a correction that is also difficult to explain but that could result simply from a faulty preliminary composition.”