Richard Avedon‘s last major photo series, “In the American West,” a landmark 1985 book and exhibition, was a massive undertaking. Ruedi Hofmann, who served as the artist’s master printer for the photographs, spent nearly three years working late into the night to complete the project.

In exchange, Hofmann alleges, Avedon promised him a set of prints from the series. And while he has many of Avedon’s prints, according to the New York Times, which has the story, they were never signed. The Avedon Foundation refuses to authenticate them, threatening legal action should Hofmann ever attempt to sell.

“Dick had no conception of what people lived on, and asking him for money was difficult,” Hofmann told the Times about Avedon. “Being paid in prints seemed the path of least resistance.” He has 126 prints altogether, each in pristine condition and carefully packed away.

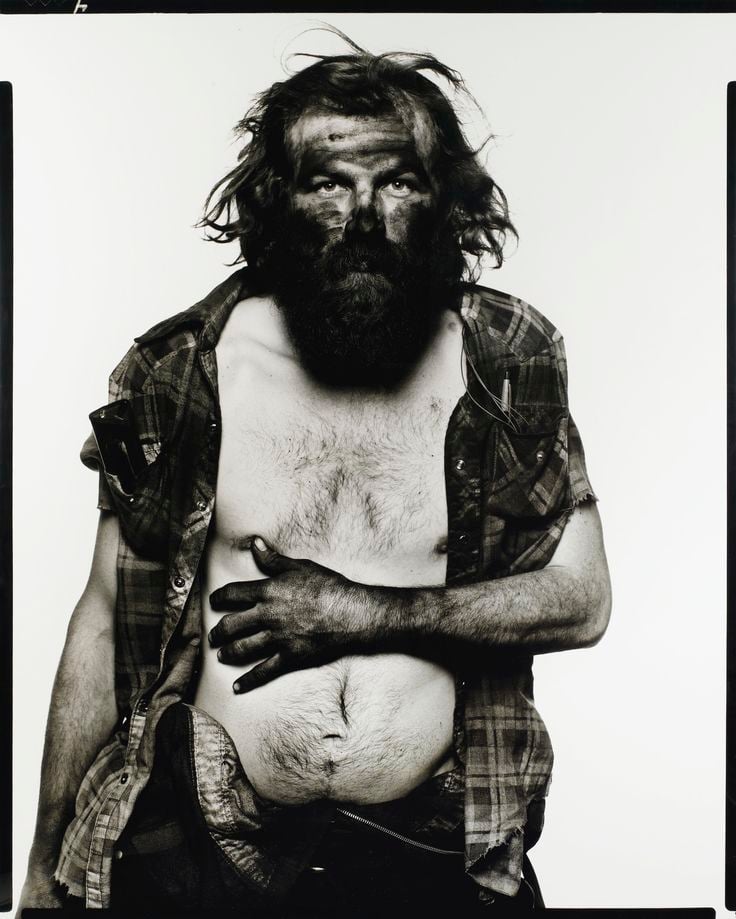

Today, those prints are potentially very valuable. Avedon’s record at auction, according to the artnet Price Database, is $1,148,910, for his Dovima With the Elephants (1955), which sold at Christie’s in 2010. Photographs from the landmark series in question haven’t reached quite that level but are still selling for hefty sums. Edward Roop, Coal Miner, Paonia, Colorado, 12/10/79 (1985), pictured above, sold for €84,600 ($90,694) at Sotheby’s Paris in November, and at last month’s Art Basel, one dealer was reportedly offering an image from the series for $155,000.

By the foundation’s reckoning, there’s not enough evidence that Avedon approved Hofmann’s prints. They allegedly have sent Hofmann a letter threatening to demand penalties of up to $150,000 per print should he reproduce the images with the aim of selling them, and to sue any buyers.

Richard Avedon, Petra Alvarado, factory worker, on her birthday, El Paso, TX (1982/1985), from the series “In the American West.” Courtesy Christie’s New York.

Supporting Hofmann’s claim is Laura Wilson, who traveled with Avedon during the creation of “American West,” documenting the making of the images. She recently wrote a letter noting that when she visited Hofmann at the photo lab in 1984, she was “stunned” by the amount of time involved to make the large prints and when she inquired about compensation for the extra work, Ruedi told her that Avedon had agreed to give him “a signed print for each image in the book and exhibition.”

And while Avedon’s studio manager at the time, Norma Stevens, also backs Hofmann’s claims, a ledger of all prints made for exhibitions kept by the artist’s studio has no record of the contested prints.

Perhaps what makes it a particularly tricky situation is that it’s not unheard of for artists’ assistants to make away with works from their employers. James Meyer, who worked for Jasper Johns, was sentenced in April 2015 to 18 months in prison for stealing 22 unfinished, unauthorized works and selling them through New York galleries. Photojournalist Steve McCurry, known for his iconic Afghan Girl image, fell victim to his studio assistant, who in April plead guilty to stealing $655,000 worth of his photos. But artists have also been known to settle checks by bartering their works in exchange for other things like food and drink such as at Paris Bar, in Berlin and, more recently, Soho House.

“The agreement was there,” Hofmann told the Times. “It just wasn’t on his mind.”