In 1902, Rainer Maria Rilke went to Paris to write a monograph about Auguste Rodin. Ten days into the trip, the young poet confessed that he had an ulterior motive for taking the assignment. “It is not just to write a study that I have come to you,” he told Rodin. “It is to ask you: how should I live?”

How a person becomes an artist was the driving inquiry of Rilke’s youth. In his twenties, the unknown poet pursued his heroes with the hope that they might teach him not just to write, but to look, think, and feel like an artist. He sought the mentor who might mold him like the raw material he described in one early autobiographical verse: “I am still soft, and I can be like wax in your hands. Take me, give me a form, finish me.”

Not many people could tolerate the needy young writer’s nagging questions for long, however. Leo Tolstoy sent Rilke away after one afternoon. The writer Lou Andreas-Salomé, his former lover, advised him for a while—improving his handwriting and masculinizing his name from René to Rainer—but then declared in 1901, “He must go!” Rilke took these rejections hard, but he persisted in his search, writing in his journal at the time that he still believed “without doubt there exists somewhere for each person a teacher. And for each person who feels himself a teacher there is surely somewhere a pupil.”

For Rilke that teacher would be Rodin, the then 62-year-old master who had just finished The Thinker. Rodin, isolated and yearning for a pupil, gave Rilke a simple answer to his immense question. “You must work, always work,” Rodin said. Do not waste time with wives and children. Do not indulge in fancy food or wine. Do not sit on cushions—“I do not approve of half going to bed at all hours of the day,” Rodin once said.

Rilke took this message to heart. He largely abandoned his new wife and daughter in Germany and stayed in Paris on and off over the next six years, first as a disciple of Rodin’s and later as his secretary. He lived in near poverty, devoting himself only to his work. When Rilke received a letter during this first sojourn in Paris from an Austrian military school student who aspired to be a poet, Franz Xaver Kappus, Rilke passed on some wisdom from Rodin, instructing him to “write about what your everyday life offers you.” Then he added a note of bittersweet encouragement: “Love your solitude and try to sing out with the pain it causes you.”

That advice appears in the first of the ten letters that would become the book Letters to a Young Poet, the beloved guide not just to writing but to navigating the solitude, anxiety, and poverty that so often attend creative life. Rilke is best known in America for this collection, originally published in 1929, three years after his death, but what readers often don’t know is that Rilke was himself a young poet of just 27 when he began writing it. What is even less known is that there is a second series of letters by Rilke to an aspiring artist—the teenage painter Balthus—written at the very end of Rilke’s life. First published in French in 1945, Letters to a Young Painter appears now in English for the first time.

These two collections bookend Rilke’s life. Taken together, the reader witnesses the transition of the artist from disciple to master. By the time Rilke was writing to Balthus, between 1920 and 1926, he was a celebrated poet living in Switzerland, in a small “stouthearted castle,” Château Berg-am-Irchel.

But fame hadn’t brought him happiness. Devastated by the First World War, he could no longer bear to even hear his native German tongue. He started writing in French instead, and changed his name from Rainer back to René. He had also begun to lament taking Rodin’s advice so literally. He had spent decades in near solitude, living only through his work. The more he thought about it, the more he began to see Rodin’s hypocrisy. The sculptor had indulged in all kinds of extracurricular pleasure, Rilke now realized, while the poet had denied himself all joy. He pledged now to do “heart-work.”

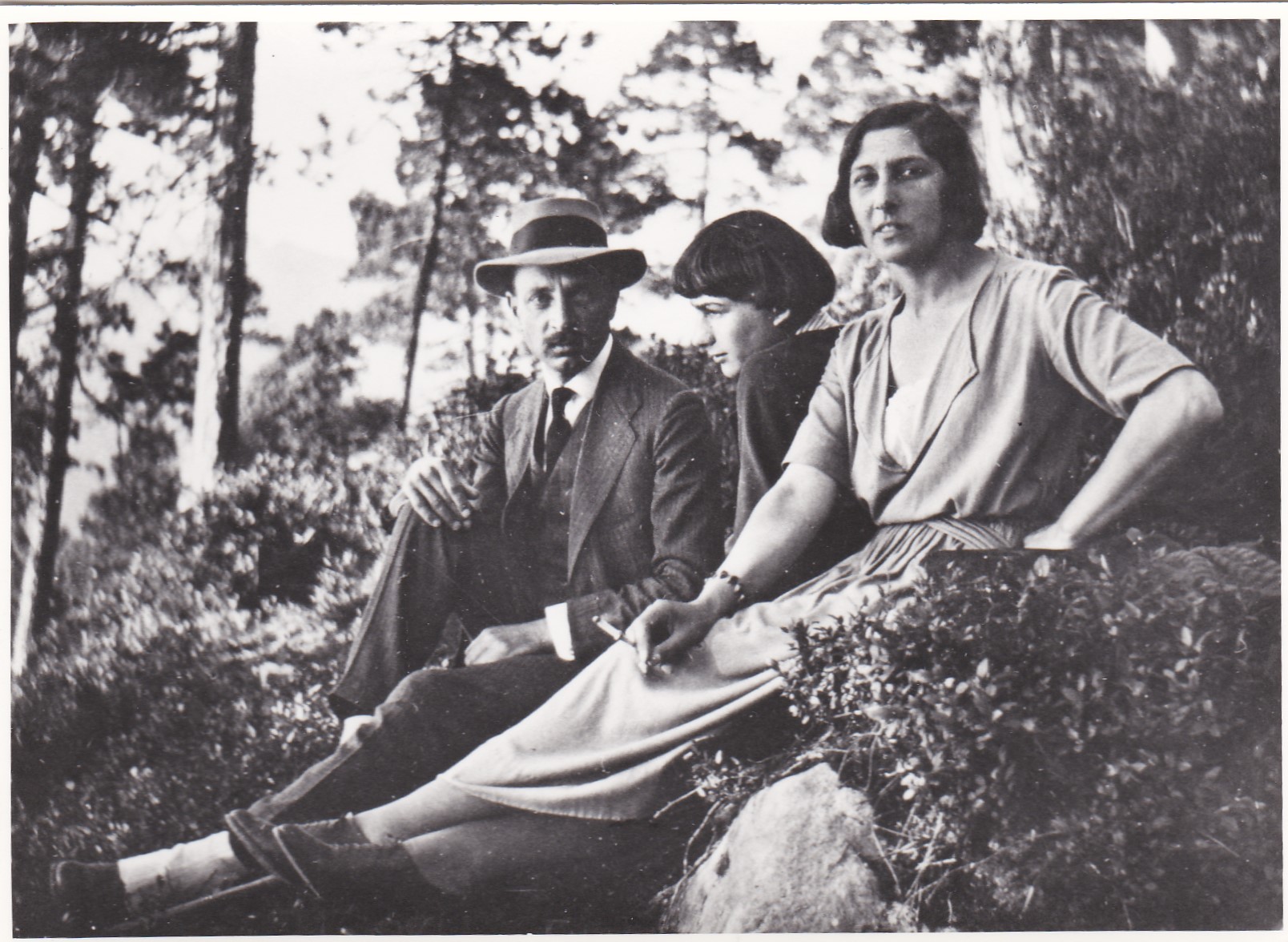

An opportunity arrived in 1919, when Rilke reunited with his old friend Baladine Klossowska, the Polish-born artist. Klossowska had recently separated from her husband and was living on her own with her two sons. Rilke immediately adored the boys: Pierre, 14, an aspiring writer, and Balthasar, 11, a precocious artist whom Rilke preferred to call by the nickname Balthus. For perhaps the first time in his life, Rilke embraced the role of father and mentor, and the foursome soon became a family. They even had a cat, an adopted Angora stray named Mitsou.

One day Mitsou ran away and left Balthasar despondent. In response to the loss, he drew 40 stunning drawings that depicted the hours he and the cat had shared together. The series begins with Balthasar finding the cat on a park bench; it ends with a drawing of him weeping for his lost companion. Rilke was so struck by the inventiveness of the works that he arranged to have them published in a book titled Mitsou, and wrote the preface himself.

It’s hardly surprising that in his later years Balthus remembered Rilke as “a wonderful man—fascinating.” The themes Rilke raised concerning Mitsou accompanied the artist throughout his career as a preeminent painters of cats; for a while Balthus even signed his name “King of Cats.”

Soon after they finished the book, Rilke’s reclusive habits returned. He shut himself up for one more solitary winter in 1922, during which time he authored the entirety of Sonnets to Orpheus. Klossowska could not bear these bouts of isolation any longer. “We are human beings, René,” she told him, and took the boys to live in Berlin.

The old lovers stayed in touch, however, and Rilke maintained close relationships with Pierre and, especially, Balthus. He arranged a job for Pierre in Paris as an assistant to his friend André Gide, and also encouraged Balthus, at the age of sixteen, to live and study art in Paris. Klossowska kept Rilke updated on Balthus’s progress. “He’s beginning to have a public,” she wrote. “René, he’ll be a great painter, you’ll see.”

Rilke did see for himself when the young artist showed him an exquisite replica he had painted of Nicolas Poussin’s Echo and Narcissus (c. 1630) at the Louvre. In its corner, Balthus added a dedication: “To René.” That same year, 1925, Rilke dedicated to Balthus the poem “Narcissus,” about a 16-year-old boy who is becoming an artist. (“His task was only to behold himself.”)

The letters Rilke wrote to Balthus in those years are markedly different than those he had sent to the young poet Kappus two decades earlier. Whereas Rilke had shunned all practical advice in his earlier letters, and declined to offer any criticism of Kappus’s poems, with Balthus he was full of praise for the artist’s “charming” work as well as advice on practical concerns. He urged Balthus to “try, make a little effort” at school, even though it was “boring.” The letters to Kappus are grandiose proclamations on love, death, sex, and life’s other big questions. To Balthus, he recounted stories about his new cat, Minot.

But where these collections converge is in the presence of Rodin. The sculptor’s teachings emerge in both books, offering an astonishing glimpse at the transmission of genius across mediums and generations. Rilke had always puzzled as a young man at the way Rodin would bid him goodnight by saying “bon courage!” But now he signed his letters to Balthus with the same words, realizing some years back how necessary courage is “every day, when one is young.”

Perhaps the most significant lesson from Rodin that Rilke passed on to Balthus was not the sculptor’s long-ago answer to the question “how should I live?” Instead, it came from the example of Rodin’s life itself. Rodin once told Rilke that when he was young he read the devotional book The Imitation of Christ, and that every time he came to the word “God” he would replace it in his mind with “sculpture.” Rilke retold this story in his first letter to Balthus, advising him to do the same with the book contract enclosed for Mitsou. Coming to the end of his life, Rilke encouraged his own dethronement. “Replace my name everywhere with yours,” he said, for although Balthus was in the eyes of the law a minor, he should nonetheless recognize the book as his own.

Rodin never questioned whether he was an artist. Rilke now urged Balthus to do the same, to not to shut himself off from the world as he himself had done for so long, but to stake his place decisively within it. See your name as the owner of this work, he said, and behold yourself: the artist.

This piece is the introduction to Letters to a Young Painter by Rainer Maria Rilke, released on November 21. The book is part of the ekphrasis series published by David Zwirner Books. Text courtesy David Zwirner Books New York/London.