Photo: Courtesy of Galerie Gmurzynska.

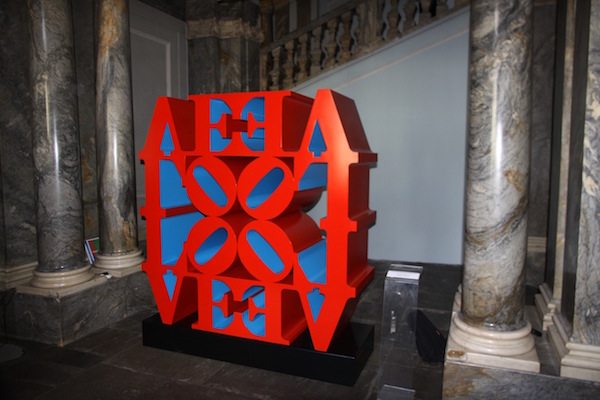

Installation of view of Robert Indiana’s retrospective at the at the State Russian Museum in St Petersburg.

Photo: Courtesy of Galerie Gmurzynska and The State Russian Museum.

There is not a lot of LOVE in Robert Indiana’s new retrospective at the State Russian Museum in St Petersburg—and the show is all the better for it.

Open to the public from April 7 through June 7, and organized in collaboration with the Zurich-based Galerie Gmurzynska, “To Russia With Love” is a triumph precisely because it is short on the work the American artist is best known for: that graphic composition of four red letters, first conceived for the New York Museum of Modern Art ’s Christmas card in 1965 and later as a postage stamp, which has cropped up all over the world in forms both sculptural and philatelic over the ensuing five decades.

“LOVE made Indiana a household name, and at the same time it ruined him,” said Mitchell Anderson, director of Galerie Gmurzynska, over a bowl of borscht in Russia’s cultural capital. “People didn’t take him seriously after that. His work is often underestimated, but when you know his early works you can see how he made his way to the late stuff. And frankly, you don’t get to artists like Christopher Wool or Jack Pierson without Indiana having paved the way.”

Robert Indiana, Love Wall (Red Blue) (1966-2007).

Photo: Courtesy of Galerie Gmurzynska.

In the spirit of righting that balance, “To Russia with Love” features just one of Indiana’s LOVE sculptures, focusing instead on six decades-worth of serigraphs, oils on canvas, and abstractions that present a side of him many have not seen. It is the first exhibition ever of his work in Russia, and confirms his pioneering role in movements from assemblage art to hard-edge abstraction—as well as Pop, though his influence is often mistakenly considered to be limited to the latter.

Indiana has said that he always felt a certain affection with Russia, even choosing to study it while he was on military duty in the 1950s, so the venue for his Russian debut—the largest museum of Russian art in the world—is apt. Beyond his cultural connection to the country (some of his artist friends in New York, including Louise Nevelson, had Russian backgrounds), there is the compelling linguistic element.

“Indiana was a great lover of typography, and the Cyrillic alphabet is beautiful on its own,” Anderson explained. “But more importantly, for a Western audience, the visual status of a Cyrillic letter is immediately separated from its meaning, and that separation was something that Bob strove for.”

Robert Indiana, Marilyn Marilyn II (1999).

Photo: Courtesy of Galerie Gmurzynska.

Born Robert Clark in 1923, Indiana moved to New York in 1954 and took up residence in Coenties Slip, at the southernmost tip of Manhattan, away from the Abstract Expressionist-dominated 10th Street scene. There, he joined a tight-knit artistic community that included Ellsworth Kelly, his mentor and briefly his lover, James Rosenquist, and Agnes Martin. In 1959, he adopted the nom-de-plume “Robert Indiana,” citing his home state, and in 1969 he left New York for good, settling in Vinalhaven, a small island town off the coast of Maine, where he still lives.

Indiana has called himself “a painter of signs,” and indeed, the metaphoric and associative power of his compositions always extended beyond their humble materials and spare, tight geometries. He had also studied literature at the University of Edinburgh, where he wrote and typeset his own poetry and prose, and words were as important to him as form. From the moment he arrived in the Slip, he was drawn to the vestiges of stenciled and hand-painted signage left all over the neighborhood from its 19th century moment as a major international shipping hub.

His earliest assemblages were made from industrial debris he scavenged around the piers, but he soon began to inject his work with more personal associations. Likely influenced by Kelly, he also began experimenting with symmetry and geometry, often organizing his compositions around orbs and executing them on cheap Homasote panels or plywood he took from his apartment’s walls.

Robert Indiana, Sixth State (1959).

Photo: Courtesy of Galerie Gmurzynska.

The show’s standout piece is one of these early “counting” pieces from 1959, part of a series in which he expressed an autobiographical narrative through numbered events or stages of life. Titled Sixth State, this humble abstraction features six golden-yellow orbs painted on a piece of found plywood. Six is his father’s number (his father’s birth month, June, and his employment at Philips 66), and it is, for Indiana, “an integer connoting conflict,” according to the show’s catalogue. Other works such as Twenty-First State feature 21 circles, commemorating his 21 childhood homes. The series offers a powerful glimpse into the way Indiana transformed real-life experiences into flat visual forms, embodying his process before his work was “corrupted by language,” to put it in his own words.

The first room of the show, though, features a lot of words, and a series of compositions he made after moving to Maine that are marked with a certain nostalgia for New York. The Brooklyn Bridge, a serigraph from 1971, includes four gray orbs containing a graphic image of the Brooklyn Bridge and lyrics from American poet Hart Crane—a sort of melancholic paean to the city he left, the center of American cultural life.

Robert Indiana, New Old Glory (1964).

Photo: Courtesy of Galerie Gmurzynska.

On the Bowery (Art), 1969-71, meanwhile, exemplifies the artist’s simultaneous flattening and exploding of images and ideas taken from the real world. Rendered in bold green, blue, and red, it is both abstract and figurative at once, containing the word “Art” within a network of triangles and rectangles, and engaging the vast range of associations that word provokes.

His 1980 “Vinalhaven suite” of 10 boldly colored serigraphs, meanwhile, compresses and contains his experiences from every year of the decade after he moved to Maine. Exhibited against bold red walls, each composition features a single number, representing one year each from 1970-1979, deconstructed into graphic and geometric design elements.

Robert Indiana, Decade: Autoportrait 1960 (1971).

Photo: Courtesy of Galerie Gmurzynska.

Decade: Autoportrait 1960, made in 1971, is perhaps the culmination of this impulse—a self-portrait through associations—encapsulating the 10 years between 1960 and 1970, which he felt were the most important of his life. Inscribed within an orb in various shades of gray, a star and the letters “IND” for Indiana are surrounded by references to his life in New York before the move, from “Pearl” and “South Street” to “Ells,” for Ellsworth Kelly.

“People always forget, until they look at Indiana’s earlier work, how he was really connecting with everyone in the whole cross-section of the 20th century, rather than just Pop art,” Anderson concluded. “In that way I think he’s a bit like Kurt Schwitters: the problem has always been that he touched all these movements, but he didn’t fit in perfectly with any of them, so it’s been easy just to push him out of the way. This show gives him new life: he just had his American moment with the Whitney show, and now begins his European moment.”

“Robert Indiana: To Russia With Love” is on view at the State Russian Museum, St Petersburg, from April 7-June 7, 2016.