In the polished (if not predictable) fashion that we’ve come to expect of HBO documentaries like “Marina Abramovic: The Artist is Present,” which provide an uncomplicated form of subject worship, “Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures” offers up a clean and heavily corroborated historical presentation of the artist’s life and work.

On a recent Tuesday evening at the Time Warner Center in New York, producer-directors Randy Barbato and Fenton Bailey revealed at an advanced screening that over fifty interviews with friends, family, and collaborators were conducted for the film.

It’s hard not to read this number as an almost defensive posture, however. Was it a precursory apology to fans? After all, the artist’s legacy is as tenacious as it is due in no small part to its ties with a painful, albeit not-so-distant event in American history: the AIDS crisis.

The documentary positions Mapplethorpe as a gay icon with an opening clip of Jesse Helms, then-Republican senator of North Carolina. Months after Mapplethorpe’s death in 1989, a full-scale show of his works scheduled to hit DC’s Corcoran gallery sparked a national conversation about the government’s financial involvement in the arts.

As the clip shows, Helms—trembling with contempt and staged to represent the very conservative pole that renders Mapplethorpe’s images deviant—is seen calling the photographs indecent on the senate floor. “Look at the pictures,” he exclaims. “Just look at the pictures!”

The opening tells us that to talk about Mapplethorpe is to talk about the sexual underground to which he will always be tied; but it doesn’t take long before the film shifts gears into Mapplethorpe’s personal world—or at least attempts to.

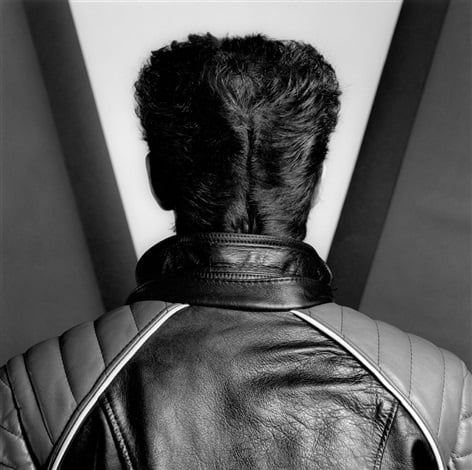

Robert Mapplethorpe, Ken Moody (1983).

Photo: Courtesy of artnet.

If the film aimed to be the “definitive” documentary on the artist, it succeeds if only for its ability to gather the collective voices of Mapplethorpe’s social and professional court; though, notably, there were some key people missing. Patti Smith, for instance, surfaced in the documentary through select audio recordings. As his friend, muse, and companion, Smith’s absence is palpable and disappointing.

While there were times when the sheer number of testimonies felt overwhelming, if not altogether heavy-handed, the interviews do, however, yield a number of memorable moments.

A conversation with Nancy Rooney, the artist’s older sister, includes rare and tender family footage of Mapplethorpe as a young boy showcasing his skills as the neighborhood’s pogo stick champion. College friend Fern Logan tells us with endearment that Mapplethorpe was the best kind of “fuck-up.” And his younger brother Edward Mapplethorpe relays an artistic tension born out of sibling rivalry.

These, again, are just a few of the stories that made the cut. Others invited to the mix include models Ken Moody and Lisa Lyon; lovers Jack Fritscher and Milton Moorel; musician Debbie Harry, and writer Fran Lebowitz. The list goes on.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Lisa Lyon (1982).

Photo: Courtesy of artnet.

One wonders what Mapplethorpe would think of the film. As he’s heard saying in a rare audio recording in the documentary: “I’m a perfectionist. It’s hard to be a perfectionist because nothing is perfect.”

Recalling fond memories as Mapplethorpe’s contemporary and friend, gallerist Mary Boone, who also appears in the film, told artnet News in a phone interview: “Early on, what he was doing was very important. It was beautiful work and it also documented a time.”

But Boone was apt to remind us that the times were markedly different, and artists’ attitudes to financial gain were equally as complicated.

“I think he wanted to have a legacy,” Boone explained. “He wanted to leave an impression, and I think he had a lot of time to think about mortality and immortality. I think immortality was more of a concern than just making money and being with glamorous people.”

Robert Mapplethorpe, Embrace (1982).

Photo: Courtesy of artnet.

For what it is—which is an ambitious documentary condensed for easy consumption—the film serves as a much-needed entry point for those unfamiliar to Mapplethorpe’s work. But for the ones who were spoiled by the kind of textured and poetic experience of the artist that, say, Smith was able to achieve in her memoir, there might be a greater connection to be had by simply looking at the pictures.

Readings of Mapplethorpe run the gamut from “martyred saint” to “Satanic exploiter,” all depending on which side of the line you find yourself; and while the film’s first-hand accounts may be informative and colorful, their offerings might still pale to what the images can say about the artist on their own.

“I want to see the Devil in us all,” Mapplethorpe said. “That’s my real turn on.”

“Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures,” premieres Monday, April 4 on HBO.