A version of this story first appeared in the spring 2021 Artnet Intelligence Report, which you can download in full for free here.

“One name keeps cropping up in regard to people not to be trusted due to their links with forgeries—that of Giuliano Ruffini.”

So begins a 3,000-word anonymous letter sent to the Paris art crime squad in 2014 that set in motion a chain of events destined to throw the Old Master market into turmoil.

The missive—which has never before been made public—called for “an investigation into the origins of works that have appeared from nowhere.” Over the previous 20 years, the letter claimed, Ruffini had encountered “problems with dealers and auctioneers in France, London, and Italy.” The author identified him as a “dealer in all but name” whose activity could be described as “diabolical… given the very high quality of his fakes,” exemplified by an allegedly faux Venus by Lucas Cranach sold to the prince of Liechtenstein for €7 million.

The author cited a technical report on the Cranach painting by a London restoration firm that stated the painting’s craquelure, or network of tiny cracks, seemed “to have appeared recently and suddenly”—suggesting the canvas had been baked to artificially provoke aging.

This claim, it turns out, was a complete fabrication. The London firm’s report, which Artnet News has obtained in full, makes no mention of the presence of craquelure.

Quite the opposite: It states that “no cracking is visible, even under magnification.” This did not deter the poison-pen writer from asserting that, after supplying vintage paints to various accomplices (“the most important of them living a few miles from his Italian home” in Codena), Ruffini had baked their canvases “in an oven to create the craquelure one would expect” in an older work.

“It seems there is a well-hidden oven at his Codena property,” the letter concluded melodramatically. “Everything can be found if you look hard enough.”

***

In the nearly seven years since the letter was sent, this scandal—now known as “the Ruffini affair”—has engulfed figures ranging from curators at the Louvre to leading auction-house executives. It has also given rise to an endless litany of conflicting and sometimes changing opinions, both technical and connoisseurial.

While those outside the specialized Old Master sector might assume the question of whether or not an object is authentic is a simple matter of yes or no, artworks can in fact pass through a number of different classifications (manner of, follower of, attributed to) before they reach full-blown attribution. The Ruffini affair reveals just how often works can slip between these categories—with millions of dollars and professional reputations on the line.

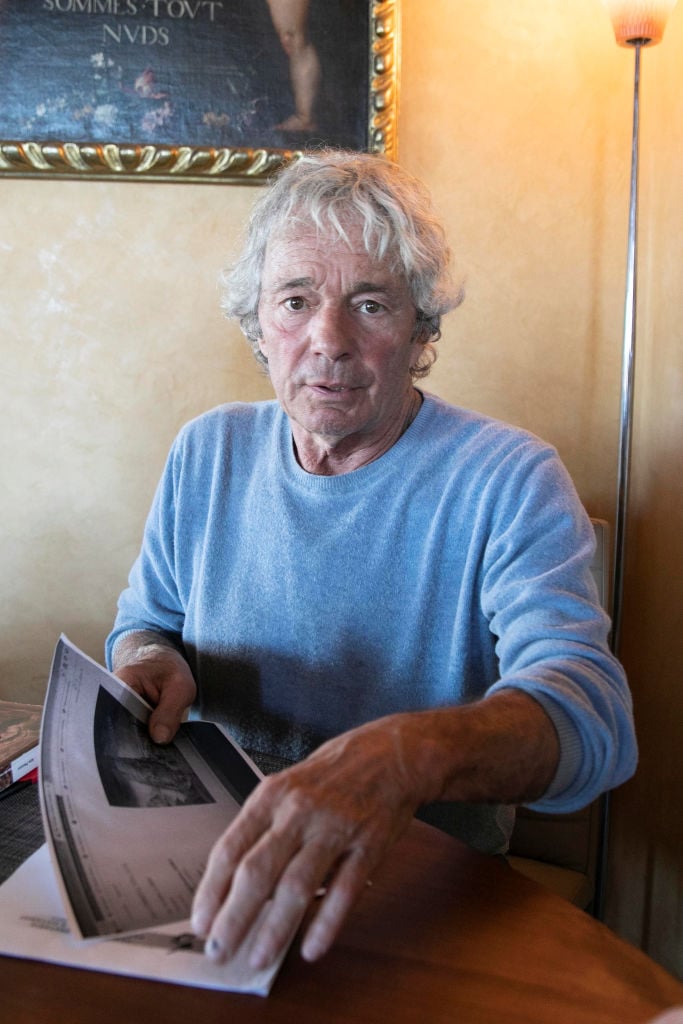

In a series of interviews conducted over several months in 2020, Ruffini—who had spoken to the press only three times before—claimed that his reputation has been unfairly tarnished and that the truth surrounding the complex scandal has yet to be exposed. Now, he has decided to tell his side of the story.

Regardless of the outcome of the lawsuits in which he is embroiled, the scandal’s impact on the art world is irreversible. It has enabled an auction house to be widely perceived as a self-appointed arbiter of artistic authenticity while offending one of France’s leading cultural benefactors (the prince of Liechtenstein), incensing Italian courts, and casting opprobrium on Ruffini, who has been the biggest loser in the affair that bears his name.

***

The origins of the saga can be traced back to 2000, when Ruffini met a Parisian by the name of Jean-Charles Méthiaz at a dinner party in Milan. The two—born a year apart—hit it off. Soon afterward, Méthiaz visited Ruffini at his Italian farmhouse, where the host cooked a huge salmon in an industrial oven he had installed to cater lavish parties thrown by his teenage son.

At the time, Méthiaz’s art-world knowledge was confined to an acquaintance with second-hand Art Deco, which he acquired while working for a former girlfriend at the Paris flea market. Ruffini, on the other hand, had been buying and selling Old Masters for three decades.

The two lost touch in the ensuing years but reconnected at the home of a mutual friend in Paris in 2010. As Ruffini tells it, it was partly because he felt sorry for the peripatetic Méthiaz and partly because Méthiaz could speak English that Ruffini (who speaks only French and Italian) offered him the opportunity to sell paintings on his behalf for a generous 20 percent commission. Méthiaz established a one-man company in Delaware, The Art Factory, to handle his art business.

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Venus (1531). The painting is now believed to be a fake. ©Liechtenstein. The Princely Collections, Vaduz–Vienna.

One of the works that Ruffini entrusted to Méthiaz was the Venus purportedly by Lucas Cranach that would later star in the poison-pen letter. Méthiaz signed an agreement with Ruffini in November 2012 and promptly went to see Elvire de Maintenant, an Old Master expert at Christie’s Paris, about the painting. He told her—as she later reported to French police—that he had “found a Cranach in a Belgian private collection” and had “bought it for around €3 million.”

A viewing of the painting was arranged in Christie’s Brussels office before the end of the month, at which the work—designated as “Lucas Cranach, Venus,” with the vendor identified as “Jean-Charles Méthiaz (on behalf of The Art Factory)”—was assigned a “provisional estimate” of £3 million to £5 million and dispatched to London for analysis by three different specialists.

Their reports, obtained by Artnet News, were somewhat inconclusive. A technical expert found “many aspects of the painting consistent with the period of the artist”; a dendrochronology consultant thought it was painted on a “most peculiar piece of wood”; and the firm R.M.S. Shepherd Associates declared the picture “of very high quality”—but felt “the poor condition of the panel does not square well with the superb state of preservation of the paint.” Given the uncertainty, Christie’s decided not to proceed with the sale.

Ruffini says he was not apprised of Christie’s findings, even though he called Méthiaz “at least once a fortnight” to ask about the painting’s whereabouts. (Méthiaz disputes this version of events, asserting that he kept Ruffini informed of his progress.)

Still, the two continued to do business together. The following year, Méthiaz visited Ruffini in Paris and offered to buy from him a youthful El Greco—which Ruffini had bought at auction for €7,500 in 2000—for €560,000. The sale agreement, reviewed by Artnet News, was addressed to Méthiaz personally (as opposed to the business address he used for The Art Factory). This transaction, according to Ruffini, was an anomaly, as it was more common for him to consign works to Méthiaz than to sell them to him outright.

Left, a legitimate sale document signed by Ruffini. Right, an alleged fake document that Ruffini said he never signed.

There may have been more to Méthiaz’s visit than that single sale. According to documents submitted to civil court by Ruffini’s lawyer, a second agreement for a different work was produced in Ruffini’s name bearing the same date—this time, addressed to The Art Factory. It concerned the sale, for €510,000, of an “oil on panel dated 1531 attributed to Lucas Cranach the Elder,” known as Venus With Veil. Ruffini claims he never saw nor signed such a document.

Apart from the changes to the billing address, work description, and price, this second invoice was strikingly similar to the first. Even the invoice number is identical: 044764160113. (Méthiaz says the duplicate number was a careless secretarial error.)

There was one more key difference between the two documents, however: the signatures. Three of four graphologists commissioned to examine the handwriting as part of the case concluded that the signature on the second document had been forged. (The other said it was “probably authentic.”)

Bank statements show that Méthiaz transferred €560,000 to Ruffini as payment for the El Greco on April 30. But Ruffini says he never received a second sum of €510,000 from The Art Factory—and Méthiaz has offered no proof it was ever sent.

***

On January 17, 2013, the day after Méthiaz and Ruffini met in France to discuss the El Greco, Méthiaz picked up the Venus from Christie’s in London and took it to the gallery of Mark Weiss, a veteran Old Master dealer located 250 yards from the auction house. Méthiaz was accompanied by Michael Tordjman, a Paris-based financial advisor whom he had introduced to Ruffini a year before.

According to Weiss’s account, Méthiaz represented himself as the owner of the painting. Weiss—“rather rashly,” he admitted in a statement in 2015—signed a €9.5 million deal to buy it on the spot, with a nonrefundable 10 percent deposit due within two weeks.

The contract, which was later made public through court proceedings, described the painting as “attributed by The Art Factory to Lucas Cranach the Elder.” The work, it stated, had been the subject of “in-depth research” by Christie’s, which had provided a “favorable opinion.”

When Weiss called a high-placed friend at Christie’s to brag about his purchase, however, he learned that the house had doubts about Cranach’s authorship. He immediately contacted Tordjman and Méthiaz and told them the deal was off.

That was not the last the world would see of the picture. It resurfaced at TEFAF Maastricht, the world’s leading Old Master fair, the following March. (Although it wasn’t on view publicly, nonparticipating dealers, brokers, and collectors often use the event as an opportunity to do business.) Before the fair was over, Jean-Charles Méthiaz’s Art Factory drew up a purchase agreement transferring the painting, “attributed to Lucas Cranach the Elder,” to Michael Tordjman’s Skyline Capital for $700,000.

That same day, Tordjman drew up another contract, committing to sell the Venus for €3.2 million to Konrad Bernheimer, the then-owner of the storied Old Master gallery Colnaghi. This time, the painting was no longer “attributed” to Lucas Cranach the Elder but unequivocally ascribed to him. (Tordjman did not respond to questions about this transaction.)

Tordjman, documents suggest, assured Bernheimer that the picture was a family heirloom and had spent the past 150 years in Belgium (Colnaghi would later publish this provenance on its website). No mention of Méthiaz or The Art Factory appears in the sale contract. The €3.2 million—which, sources allege, Tordjman split with Méthiaz, although neither has commented on this point—was to be paid into Tordjman’s bank account in Singapore. Ruffini says he was not informed of the sale.

The work did not stay in Colnaghi’s storeroom for long. On July 1, at the tony Masterpiece fair in London, the gallery triumphantly announced it had sold the Venus to the prince of Liechtenstein. The price: €7 million.

Méthiaz headed to a large villa in southern Italy that he had purchased a few weeks earlier. “His lifestyle changed overnight,” recalls his acquaintance Raphaël Wertheimer. “He boasted to me about buying a boat and a house in Apulia.”

***

Giuliano Ruffini remained blissfully unaware of the Cranach’s fate. He assumed Méthiaz was still having the work tested and looking for a buyer. He was disabused by art broker Giammarco Cappuzzo, who told him about a Lucas Cranach the Younger he had recently sold to Mark Weiss.

“May have a Cranach myself!” Ruffini replied, bringing up a photo on his cell phone. “It’s with a friend, we’re having it studied. Had it over 30 years—never been on the market.”

Cappuzzo recognized the painting immediately. “Colnaghi sold that for €7 million at Masterpiece,” he said. Ruffini’s face, Cappuzzo recalled later, “turned all the colors of the rainbow.”

From this moment forward, the situation began to deteriorate. In January, Ruffini and Cappuzzo visited Konrad Bernheimer. As Ruffini recalls, Bernheimer showed them the invoice confirming he bought the Cranach from Michael Tordjman. Ruffini promptly emailed Tordjman to announce he was “canceling all my contracts with The Art Factory and your friend Méthiaz.” Ruffini emailed Méthiaz a few days later, snarling, “I never authorized you to sell my Cranach…. You’re the worst piece of shit I’ve ever come across.”

Ruffini filed a civil lawsuit against Méthiaz, Tordjman, and The Art Factory on May 2, 2014, for allegedly defrauding him of €3.2 million in the sale of the Cranach. Méthiaz’s defense revolved around the January 16, 2013, contract, in which Ruffini supposedly ceded the Cranach to The Art Factory for €510,000. Tordjman’s lawyer asserted that Tordjman, for his part, “bought the work from The Art Factory through the intermediary of the Skyline Capital Corporation.” Tordjman himself declared the work was of Belgian provenance in a customs declaration.

***

The Paris art crime squad received the anonymous letter implicating Ruffini on May 26, 2014—just 10 days after the first hearing in the civil case he had brought over the sale of the Cranach.

During a preliminary inquiry into alleged forgery and fraud, Méthiaz—according to a police report obtained by Artnet News—emailed investigators suggesting they Google an Italian painter named Lino Frongia. Among the search results: an article, published in La Repubblica in 2008, that referred to him as a forger.

Two months after the preliminary inquiry was completed, French authorities launched a full-scale criminal investigation into allegations of forgery, fraud, and money-laundering. It was soon placed in the hands of examining magistrate Aude Buresi, a fiscal specialist (who, over the next five years, would investigate former French Prime Minister François Fillon and former President Nicolas Sarkozy).

Buresi lost no time in asking the procurator of Reggio Emilia to have the Guardia di Finanza, Italy’s financial crime squad, check out Giuliano Ruffini and Lino Frongia. Buresi appeared to be taking the poison-pen letter’s view that “the fiscal aspect is important as, relatively speaking, this may cause [Ruffini’s] downfall, like Al Capone.”

The Guardia reported that Frongia had a “reputation for morality and good conduct.” Ruffini had been fined 40,000 lire (about €20) in 1973 for illegally possessing a firearm, and 300,000 lire (€155) for assault in 1984.

Buresi also asked the Guardia to look for a “hidden oven” used to “give paintings craquelure to create the illusion of age.”

At dawn on January 28, 2016, the Guardia swooped down on the homes of Ruffini and Frongia, impounding computers, phones, pictures, and paperwork. The search of Frongia’s residence, according to a Guardia follow-up report, “confirmed that painting is his main activity—his dwelling had a very large studio.” The search of Ruffini’s, the Guardia boasted in bold capitals, yielded “POSITIVE results,” with the discovery of a concealed industrial oven “supporting the hypothesis of criminal activity.”

But the oven may not have been the smoking gun it seemed to be. As the Guardia acknowledged, it was Ruffini who volunteered its existence, welcoming them into a compartment behind an armored door in his laundry room. (Ruffini said he originally carved out the space to store valuables.)

Ruffini was unaware of the poison-pen letter at the time of the Guardia’s raid—his lawyers learned of its contents only in 2017—and failed to realize the oven’s significance.

“I had the industrial oven installed in the laundry because there was nowhere else to put it,” he says. “The oven was used for bread, pizzas, fish…. I’ve owned two restaurants. There’s nothing unusual about a cook having a large oven!”

Ruffini dismisses out of hand the accusation that he used the oven to “bake” paintings. “It was an old artisanal oven with large electrical resistors,” he says. “If you tried to dry paintings in it, the vapors would have caught fire at the merest spark.”

During the raid, the Guardia confiscated 15 paintings from Ruffini’s home. But on February 15, the criminal court of Reggio Emilia ordered them to be returned.

“There is nothing to suggest these paintings are fakes,” the court stated. “The supposed faking appears to have been evoked by a confidential source [i.e. the anonymous letter] which can in no circumstances be taken into consideration.” (Italy’s criminal procedure code outlaws the reliance on anonymous accounts in a judicial context.)

Emboldened by the oven-yielding Codena raid and undaunted by the Italian court’s response, Aude Buresi had the Cranach Venus impounded in Aix-en-Provence on March 1. (Buresi did not respond to questions for this story.) The painting was on view as part of a traveling exhibition of the collection of the prince of Liechtenstein. It had been the exhibition’s catalogue cover and headlined its PR campaign.

The confiscation was an unheard-of offense to the prince, who had lent hundreds of works to French institutions from his opulent holdings. He was outraged by Buresi’s behavior and immediately filed a claim to register his concern with the investigation.

The Cranach was taken to Paris for analysis by a forensic scientist and a graphologist, both appointed by Buresi. The former cast doubt on the painting’s authenticity because the paintwork on the figure of Venus displayed craquelure but not the black background.

Experts connected with the prince’s collection claimed this was normal for works of the period and “remained fully convinced of the painting’s authenticity,” according to a statement issued that fall by Johann Kräftner, the collection’s director.

The situation was ubuesque: A painting considered bona fide by its lawful owners remained confiscated as a fake by the representative of a foreign state.

***

While the criminal investigation sparked by the poison-pen letter was humming along, the civil proceedings hit a snag. On June 30, 2016, 12 weeks before the date of the final hearing, the case pitting Ruffini against Méthiaz and Tordjman was suspended—for four years, as it would happen—due to what the court described as “doubts about the Cranach’s authenticity” and an ongoing “investigation concerning an international network of forgers.”

The suspension of the civil suit confirmed Ruffini’s belief that Méthiaz was the author of the poison-pen letter. He knew about Ruffini’s hidden oven; the letter also included a reference to an artwork that Ruffini says only Méthiaz knew he owned.

“Je l’ai bien baisé ce Rital” (“I really screwed that Italian”), Méthiaz told Raphaël Wertheimer in 2014—the same year the poison-pen letter was sent—according to a sworn affidavit Wertheimer supplied to Ruffini’s lawyer. There were other coincidences, too: Both the anonymous letter writer and Méthiaz (in Facebook posts) evoke the devil and Al Capone in connection with Ruffini. Both combine references to Al Capone with praise for Italy’s Guardia di Finanza, and both use the verbose French phrase toutes proportions gardées (“relatively speaking”), misspelled on each occasion.

Asked to respond to Ruffini’s allegation that he was the author of the poison-pen letter, Méthiaz issued no denial but claimed that Ruffini had previously declared its author to be Michael Tordjman. “Given all his rantings about me, what else can I say?” Méthiaz added.

The identity of its author aside, the letter did raise one important question: Where did a man like Ruffini get his hands on all these artworks—which, depending on whom you ask, were either overlooked masterpieces or dubious fakes?

A trawl through Ruffini’s past suggests a remarkable story of a street-wise immigrant with a passion for art, women, and wheeling and dealing who has been compulsively scouring galleries, flea markets, and antique fairs for over half a century.

***

Ruffini was born in 1945 in a farmhouse 30 miles south of Parma but grew up in Paris, where his father was a cobbler. In 1961, he fled with a girlfriend to Cannes, where he began to paint. His works caught the eye of singing legend Damia, who arranged a show for him at Galerie du Colisée, off the Champs-Elysées, in 1964. It sold out.

Ruffini blew his windfall on the Riviera high life, then left to see the world—working in Rome (painting furniture), Australia (as a cook), New Caledonia (as a newspaper cartoonist), and the Ivory Coast (as artistic director for Inter Afrique Presse). He returned to Europe in 1971 and opened an art gallery in Castelnovo ne’ Monti, near his birthplace. On a trip to Paris, he visited La Brocanterie du Marais, an antiques gallery just off Place des Vosges. Ruffini, then 26, and its 50-year-old owner, Andrée Borie, became lovers.

Borie was childless, twice divorced, and mourning the recent death of her father, André Borie, who oversaw the construction of the Mont Blanc Tunnel. His obituary in Le Monde dubbed him “rustic yet refined,” adding, “His level of culture took technocrats by surprise.”

A list of six paintings ceded to Ruffini from André Borie’s collection, gifted to him by his daughter, Andrée Borie. Courtesy of Ruffini.

Borie had lined the walls of his Paris townhouse on upscale Avenue de Wagram with pictures. Andrée’s elder sister, Georgette, inherited his Modern pieces; Andrée, his Old Masters. She put some in her shop and consigned others for auction at the city’s Hôtel Drouot. Ruffini contends that Borie also gave a few of them to him as gifts: Six works from “la collection de Monsieur ANDRE BORIE” are recorded in a typewritten list as ceded to Ruffini on April 4, 1973 (his 28th birthday).

Borie closed her gallery in December 1974. A year earlier, she and Ruffini had purchased a 150-acre farm at Codena, near Ruffini’s birthplace in the Apennines. The walls were festooned with Old Master pictures, some of them unsold stock. An early client, Adelio Bertolazzi, recalls the youthful Ruffini as “kind and sensitive… he loved art.” Bertolazzi described Andrée Borie as “very much in love with Giuliano and always giving him presents.”

Bertolazzi still owns three works he acquired in Codena, including a Crucifixion he bought as by the “circle of Guido Reni” but that appears to have served as the model for the Martyrdom of St Andrew painted by French artist Guillaume Courtois for Sant’Andrea al Quirinale in Rome in 1668.

Andrée Borie died of a heart attack in March 1980. Partly for fiscal reasons and partly due to his innate wanderlust, Ruffini went on to live in Florence, Rome, Madrid, Paris, Brussels, and Malta, running a piano bar, giving karate lessons, and opening an ice-cream parlor along the way. He gained access to the Madrid art scene through a Spanish socialite he met. The Franco dictatorship had placed Spain off-limits to the European art trade for decades, and, Ruffini says with a grin, “it was full of big collections.”

He also befriended artist Lino Frongia, a graduate of the Parma Fine Art Academy. Ruffini says he admired Frongia’s art-historical knowledge and painterly savvy and would “seldom buy a painting without sending Lino a photo—he told me if it was a copy or an original. He taught me a lot.”

The first public evidence of Ruffini’s own phenomenal eye came in early 1992, when he bought a damaged Étude du Christ that Paris auctioneer Francis Briest had catalogued as “School of Correggio.” It came with a 1970s certificate by Roberto Salvini (the onetime head of the Uffizi), which, being written in Italian, Briest appears not to have read. It asserted that Salvini had “no doubt” the painting was a youthful work by Antonio da Correggio himself. The Museum of Correggio bought it from Ruffini for 350 million lire (€180,000) in 1997.

Apart from the Venus, the only work of importance that Méthiaz was actually involved in selling was a David & Goliath on lapis lazuli entrusted to him by Ruffini as a “19th-century copy” of larger versions of the subject by Orazio Gentileschi in Rome’s Galleria Spada and Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie. A contract signed by both Ruffini and Méthiaz, which was reviewed by Artnet News, states that the painting should not be sold for less than €2 million.

Orazio Gentileschi, David Contemplating the Head of Goliath, now thought to be a forgery. Courtesy of the Weiss Gallery.

Méthiaz showed the work to Francesco Solinas, cocurator of a forthcoming Paris exhibition devoted to Orazio’s daughter Artemisia. In a letter to a fellow curator, Solinas wrote that he was enthralled by this “extraordinary” picture, whose “assured, lengthy, vigorous brushstrokes” had all the elegance and precision of a true Orazio Gentileschi.

A freshly discovered Gentileschi was sensational news. Mark Weiss was so impressed he asked his Paris broker, Giammarco Cappuzzo, to arrange a meeting with Méthiaz, whom Cappuzzo believed to be the work’s owner.

After agreeing with Weiss on a price of €3.6 million, Cappuzzo recalls, Méthiaz took him aside and asked him “not to say anything about this to Giuliano Ruffini.” Cappuzzo found the request “bizarre.” It wasn’t: According to Ruffini, Méthiaz later told him he’d sold the Gentileschi for just €1.4 million. Ruffini, who should have received €2.88 million (once Méthiaz had deducted his 20 percent commission), instead received €1.12 million. A copy of Ruffini’s bank statement shows The Art Factory transferred the sum (in dollars) to his Monaco account on May 2.

***

Another ex-Ruffini work was caught up in the whirlwind that engulfed the art world after the Cranach seizure: a portrait of a young man that Ruffini had bought as “attributed to the workshop of Frans Hals” for €8,000 in 2000.

When Ruffini showed Portrait of a Man to specialists at Christie’s Paris in 2008, he

says, they proposed offering it for sale with a higher classification, “attributed to Frans Hals,” and an estimate of $300,000. But its export was blocked by the French state, which deemed the work a national treasure and offered the Louvre the chance to buy it for €5 million.

Frans Hals, Portrait of a Man, one of a series of Old Master works sold by a French dealer that authorities now believe may be forgeries. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

While the Louvre was working to raise the funds, Ruffini—in need of cash, he says, to build a palatial house for his beloved only son, Mathieu—sold the painting to Mark Weiss for €3 million in a deal partially financed by Fairlight Art Ventures LLP, a company funded by hedge-fund manager David Kowitz. When the Louvre failed to raise the €5 million, Weiss sold it via Sotheby’s to a company owned by Seattle billionaire Richard Hedreen for $11.29 million.

Six years after the sale, new developments cast the picture in a different light. Sotheby’s had been alarmed to learn that both the Hals and the recently confiscated Cranach had been owned by Ruffini. The auction house contacted Hedreen—one of its biggest clients—and arranged for a technical inspection of the work by a forensic laboratory in Massachusetts called Orion Analytical.

“Sotheby’s stands behind our authenticity guarantee and contractual obligation to the buyer of a work, with the expectation that the seller stand behind their obligation as well,” a representative from the auction house says.

Lab owner James Martin is best known for his work with postwar art, having helped resolve a scandal that had embroiled New York’s venerable Knoedler Gallery a few years earlier by identifying anachronistic pigments in purported Abstract Expressionist paintings. (Domenico de Sole, the chairman of Sotheby’s board, reached an out-of-court settlement with Knoedler over his purchase of a fake Rothko based in part on Martin’s evidence.)

Martin discovered in the Hals plastic-coated air abrasive (colored with phthalocyanine blue) and coarse agglomerates that contained titanium white—materials first produced in the 20th century. The air abrasive, he said, likely was used to strip decorative paint from the centuries-old wood panel for reuse, while he attributed the titanium dioxide to dust in the studio where the fake was painted. His conclusion that the portrait must have been painted “after the mid-20th century” made the Louvre (which had spent more than two years trying to buy it) look like a Mickey Mouse outfit.

Sotheby’s found Orion’s work on the Hals so satisfactory that, in December 2016, it bought the company and made James Martin a director (later promoting him to chief science officer).

The house also sued Weiss and Kowitz’s Fairlight Art Ventures. Weiss—who maintains to this day that the painting is authentic—agreed to pay £3.2 million in an out-of-court settlement. Fairlight was ordered to pay Sotheby’s £4.5 million by the London High Court in December 2019, although, when delivering the ruling, Justice Knowles insisted that his judgment was based solely on the terms of the contract and “does not determine whether the painting is by Frans Hals…. It is to be hoped that its intrinsic qualities will not be ignored, and that it might be enjoyed for what it is, which is a fine painting.”

It was refreshing to hear someone—significantly, someone not connected to the art world—talk about a work of art in terms of its intrinsic quality rather than obsessing over its commercial value and who exactly painted it. Beauty would be sacrificed on the altar of scientific data throughout the Ruffini affair.

Justice Knowles was no doubt aware of the 147-page, 30,000-word report on the Hals by German forensic scientist Erhard Jägers, commissioned by Mark Weiss and submitted to the London High Court. (Its contents have not been made public until now.)

In it, Jägers describes Martin’s findings as “fundamentally flawed.” He contends that the areas on the painting where Martin found particles of phthalocyanine blue and titanium white (including the top layer of varnish) were irrelevant to its authenticity.

“It appears,” he wrote, that Martin “sought out areas of loss and damage which would

corroborate his views.”

Sotheby’s claims that Martin’s in-depth analysis was “peer reviewed and endorsed

by another leading independent scientist in the field.” Furthermore, a statement from

the auction house reads, the judge “accepted that Sotheby’s made a reasonable determination in deciding to rescind the sale on the basis of our assessment that the work was not authentic” and “was quoted as stating that they were ‘satisfied that Mr. Martin worked conscientiously and expertly, to a high professional standard and with professional integrity.’”

Jägers, for his part, thought it impossible for a modern forger to have created such a

“complex, multi-layered structure.” The portrait’s pigments were commonly used in the

17th century; dendrochronology suggested that the oak panel dated to 1588 or later.

Jägers also addressed the technical findings of a report on the Hals commissioned from a technical expert by Aude Buresi. He disputed its claim that “lead soaps and their protrusions can be accelerated artificially by means of heat.” On the contrary, asserted Jägers, “such protrusions are a well-known feature of old works… a normal reaction between oil and lead. If the panel had been artificially heated, I would have expected to see more damage.”

***

Aude Buresi issued two European arrest warrants in 2019 calling for the extradition of

Frongia and Ruffini from Italy to France. They had no effect. On February 28, 2020, the Bologna appeals court dismissed all nine of Buresi’s accusations against Frongia.

Breaking the media silence he has observed since his home was raided in 2016, Frongia says he had expected the investigation to “blow over in a few weeks, once the senselessness of the accusations had become clear.” He has maintained throughout that it would be impossible for one artist to imitate so many masters so well. “To perfectly imitate just one artist would take a lifetime,” he tells Artnet News.

More than one year later, Buresi has yet to bring Ruffini and Frongia to court. Some suspect the investigation will be quietly dropped after her term ends, later this year. Ruffini, meanwhile, faces an investigation by Italian fiscal authorities, who suspect him of owing tax on the income he derived from selling art between 2013 and 2017. (Ruffini claims he is not liable for tax because he is a collector rather than a dealer and was fiscally resident outside Italy for much of that period.)

In the end, of the €6.8 million generated by Ruffini’s Cranach and Gentileschi, he received just €1.12 million. Five of the six paintings on the 1973 André Borie list have been sold, for a total of €3.65 million—of which Ruffini has received €450,000. It is hard to believe that a man of such supposedly mephistophelian cunning, accused of making his fortune by peddling forgeries, could be such a lousy businessman (and so naive and trusting in his dealings with others).

Giuliano Ruffini in Emilie-Romagne near Parma on February 5, 2020. Photo by Baptiste Giroudon/Paris Match via Getty Images.

On July 2, 2020, Ruffini’s criminal lawyer addressed a blistering note to France’s public prosecutor accusing Buresi’s investigation of lacking objectivity and impartiality, according “boundless and inexplicable credit” to an anonymous denunciation, and failing to investigate Jean-Charles Méthiaz and Michael Tordjman over the sale of the Cranach Venus.

“If the Cranach is indeed a fake,” he wrote, “Tordjman and Méthiaz are accomplices to the criminal activity of which Ruffini stands accused. If it is authentic, they are swindlers. Why have they not been asked to explain themselves?”

Through his lawyer, Tordjman has refused to offer any public comment. Méthiaz, for his part, staunchly maintains he is neither accomplice nor swindler. “The only person who could have helped the progress of investigations is Mr. Ruffini, who is perfectly aware of what he is doing,” he says. “If there is any victim in this affair, it certainly isn’t Ruffini. And I am not an accomplice to anything.”

The Venus is now due to return to its previous owner, the prince of Liechtenstein. Four years after it was confiscated, a Parisian court of appeal ordered authorities to return the work on April 15, 2021, concluding they had completed the necessary examinations and had no further grounds to hold onto it.

Ruffini and Méthiaz, now in their mid-70s, have spent the pandemic lockdown in virtual

isolation at opposite ends of Italy: Ruffini with his son Mathieu in the rugged Apennine

Hills; Méthiaz with his dogs, Oscar and Gaston, amid the olive groves of Apulia.

Ruffini has been spending his time renovating; Méthiaz, posting lengthy diatribes

on Facebook. His favorite targets: French President Emmanuel Macron (“mad, dangerous”) and Joe Biden (“Creepy Joe and his government of Village People”).

When Ruffini and Méthiaz finally emerge blinking into the sunlight, it will be at high

noon on May 20, 2021, for a shoot-out in civil court over what, in another Facebook

post, Méthiaz has dubbed “l’escroquerie du siècle”: the crime of the century.

To read more details on the disputed Ruffini works, find out what will change in the new age of cyborg art sales, and why Robert Nava may be the best bad artist ever, download the full Intelligence Report.

Simon Hewitt is the author of Leonardo da Vinci and the Book of Doom (Unicorn, London 2019). A full-length, abundantly illustrated version of his investigation into the Ruffini affair has been published on artdependence.com.