Visit the Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida this spring and you’ll be guided by special docent: Salvador Dalí himself.

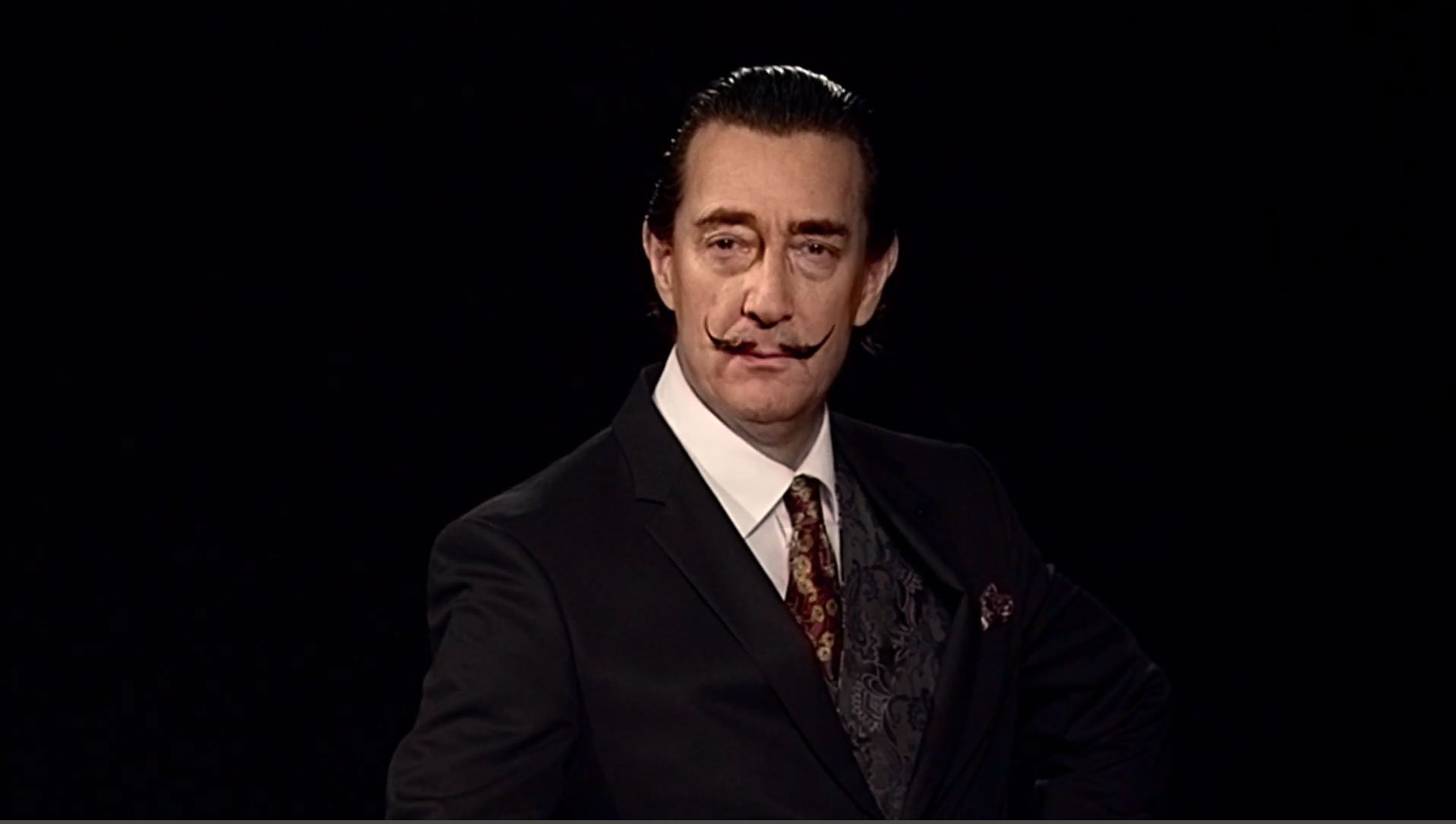

Well, an AI version of him, at least. In April, the museum will open “Dalí Lives,” a new program that offers visitors the opportunity to engage with an interactive digital rendering of the artist. Walk up to one of the human-sized screens installed throughout the museum, press a button, and watch as the Surrealist comes to life.

The project arrives as museums worldwide have been exploring how to incorporate the trendiest technology, from AI to VR. Is it possible that, in 50 years, visitors will be guided around museums by digital renderings of Picasso and Matisse?

Dr. Hank Hine, the executive director of the Dalí Museum, says the project was inspired by the artist’s unique sensibility. “I think that the seeds of this project were sown by the artist himself,” he tells artnet News. “Dalí was famous for his sense of his own eternal significance. It’s almost like, if had left instructions for us, this project would have been among them.”

The museum tapped Goodby Silverstein & Partners, a creative ad agency based in San Francisco, for the project. Over the past six months, the two organizations assembled footage, photographs, interviews, and hundreds of other archival materials featuring the late Surrealist. They used the materials to train an AI algorithm to “learn” elements of Dalí’s facial movements and filmed new footage from a lookalike actor. The AI can now generate a version of Dalí’s likeness that matches the actor’s expressions.

Most of the language used by the AI is sourced from quotes by the man himself. But the character will also comment on things that the real Dalí could never have said—musings on current events, for example, or references to local sports teams—drawn from the actor.

This isn’t the first time the museum has collaborated with Goodby Silverstein & Partners. In a 2014 exhibition called “Gala Contemplating You,” the agency created a kiosk that turned visitors’ selfies into replicas of a 1976 painting of the artist’s wife. In 2016, the two organizations developed “Dreams of Dalí,” a virtual reality experience that allowed viewers to walk inside Dalí’s painting, Archaeological Reminiscence of Millet’s “Angelus” (1934).

These experiments were big hits with the community, Hine explains. In a recent poll conducted by the museum, 97 percent of guests expressed a desire for “more digital interactive experiences.”

Exterior view of the Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida. Courtesy of the Dalí Museum.

“We’re trying to make the work more easily digestible,” Hines says. “People who go to art school are taught to have a silent inquiry of a painting, to visually probe it and ask it questions about why it is the way it is. But that’s an acquired skill, and without an entry to the works it’s much more difficult. Drawing from Dalí’s own interest in media and the potential of new technologies, we have a commitment to find ways for our visitors to find delight and special kind of entry into Dalí’s spirit.”

Hines recalls one of the Dalí’s most famous quotes: “If someday I may die, although it is unlikely, I hope that the people in the cafes will say, ‘Dalí as died, but not entirely.’”

“In a sense,” the museum director says, “we have made his words prophetic. We’ve brought him back to life!”