In 1919, while at school in the Spanish city of Figueres, a 15-year-old Salvador Dalí volunteered to write a series of articles for the school’s magazine, Studium. Titled “The Great Masters of Painting,” the assignment allowed Dalí to study and pay tribute to the artists he most admired, including the 17th-century Spanish court painter Diego Velázquez, whose “color distribution and placement” he saw as a precursor to Impressionism and, by extension, Surrealism.

Nowadays, most people view Dalí’s work as sui generis: a dazzling Surrealist concoction of dreamlike imagery that has little to do with the waking world, much less with the artists who came before him. But as the anecdote above indicates, Dalí was anything but disconnected from art historical tradition. Not only do his paintings draw on religious and historical imagery, but he also considered himself deeply indebted to scores of European artists, from Velázquez to Albrecht Dürer.

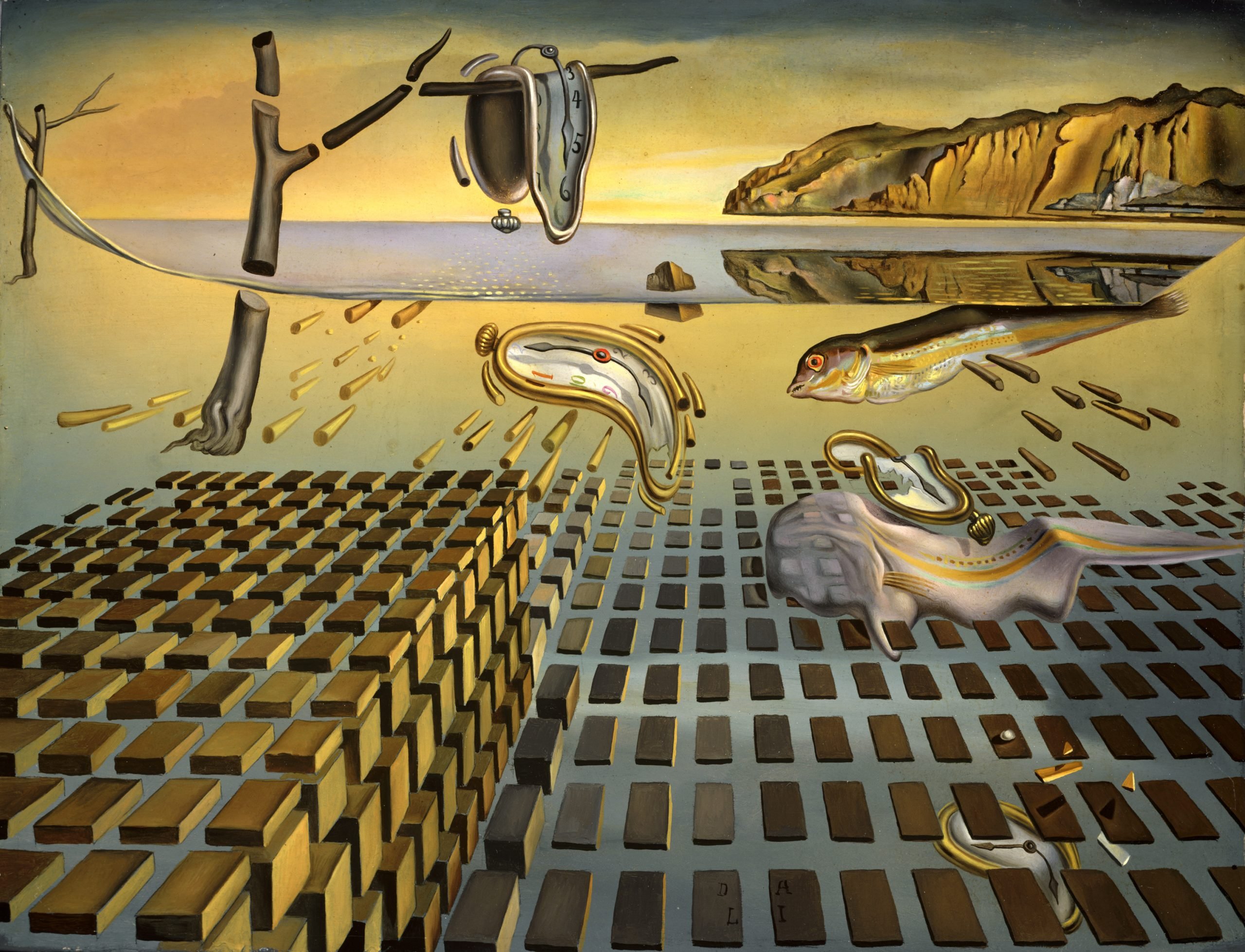

Salvador Dalí, Old Age, Adolescence, Infancy (The Three Ages) (1940). Courtesy: The Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg/Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

That indebtedness is on full display at “Dalí: Disruption and Devotion,” an exhibition at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), which places Dalí’s work side by side with that of his favorite classical painters from Spain, Italy, and the Low Countries of Belgium and the Netherlands, all while highlighting how the ever-eccentric Surrealist had to learn the rules of traditional painting before he could effectively break them.

“Even as a teenager, Dalí looked to great artists of the past for guidance and inspiration,” Julia Welch, the MFA’s assistant curator of paintings, art of Europe, said in an interview. “He frequently referred to a series of art books that he had as a child, which introduced him to many great artists of the past, and for Studium [he] wrote about Velázquez, Dürer, Goya, Leonardo and Michelangelo.”

“Dalí: Disruption and Devotion” exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Photo: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Although Dalí was drawn to art from many countries and cultures, he gravitated most towards painters from his native Spain. “Many major Spanish artists held particular significance to him,” notes Welch, “having spent many hours roaming the galleries at the Prado Museum while a young art student in Madrid. Velázquez, above all, would remain one of his greatest and lasting influences throughout his long career.”

According to Welch, Dalí was drawn to the “power and strength that Velázquez conveyed through his portraiture.” He attempted to channel Velázquez’s “vigor and energy” into Velázquez Painting the Infanta Marguerita with the Lights and Shadows of His Own Glory (1958), which shows the shadow of the Spanish master as he labors over a portrait of the future Holy Roman Empress.

Left, Salvador Dalí, Velázquez Painting the Infanta Marguerita with the Lights and Shadows of His Own Glory (1958), and, right, attributed to Juan Bautista del Mazo, Infanta Maria Theresa (previously attributed to Velázquez). Photo: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Velázquez Painting the Infanta Marguerita is displayed next to this very portrait, produced in Velázquez’s workshop and currently attributed to one of his students, Juan Bautista del Mazo.

Leonardo da Vinci also made a strong impression on Dalí. Just look at his 1935 painting Paranonia, whose small figures and horses in the background were, Welch points out, “directly inspired by Da Vinci’s sketches. Meanwhile, “the double image of a woman’s face produced within those small figures”—a hallmark of Dalí’s oeuvre—“is pulled directly from Da Vinci’s The Woman with Disheveled Hair [1506–1508].”

All in all, “Dalí: Disruption and Devotion” juxtaposes close to 30 of Dalí’s paintings and prints (loaned from the Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida) with European paintings from the MFA’s own collections, including portraits, religious and historical scenes, and still lifes by the likes of El Greco, Orazio Gentileschi, and, of course, Velázquez.

Salvador Dalí, The Ecumenical Council (1960). Photo: Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Artists Rights Society/Doug Sperling and David Deranian, 2021/Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Some of these juxtapositions are surprising, even to art historians. “One of the earliest works by Dalí in the show, Girl’s Back from 1926, is most often described in literature in connection with the Dutch predecessors, like Vermeer,” says Welch. “But we found a really interesting juxtaposition with an early portrait by Velázquez in the MFA’s collection of Luis do Góngora from 1622. In both works, there is a similar attention to the modeling of forms, the textures of hair and skin, and the dramatic use of lighting effects against dark backgrounds.”

Those visiting the exhibition may just walk away with a new conception of the artist’s work and Surrealism as a whole. Even though many of his works feature what Welch calls “bizarre, often fantastical or indecipherable imagery,” they will find, it is deeply rooted in traditions which the Spaniard held in the deepest esteem.

“Dalí: Disruption and Devotion” is on view at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, 465 Huntington Ave, through December 1, 2024.