An ownership dispute is heating up over a version of the Mona Lisa that is widely believed to be by the hand of Leonardo da Vinci.

An international consortium jointly owns the painting, but now the heirs of a man who bought a quarter share in it are suing to find out the painting’s whereabouts and the identities of its other anonymous owners in order to regain control of their interest in the work.

The consortium established the Mona Lisa Foundation in Switzerland a decade ago to research and promote the painting, which is known as the Isleworth Mona Lisa. But when the heirs’ lawyer, Giovanni Protti, reached out to the foundation, “we got no answer from them other than ‘we don’t know where the painting is; we don’t know who the owners are; we are just researchers doing attribution work,'” he told artnet News.

In order to identify the people who control the Isleworth Mona Lisa, Protti and his partner, Chris Marinello, of Art Recovery International in London, turned to the infamous Panama Papers, a cache of 11.5 million leaked documents related to offshore financial transactions.

“Through the Panama Papers, we got some information about the real owners of the painting,” Protti said. “They are very well-known figures in the art world. We assume they own the painting through offshore companies in tax havens.” Protti declined to reveal the suspected owners’ identities, but says they will come out in court.

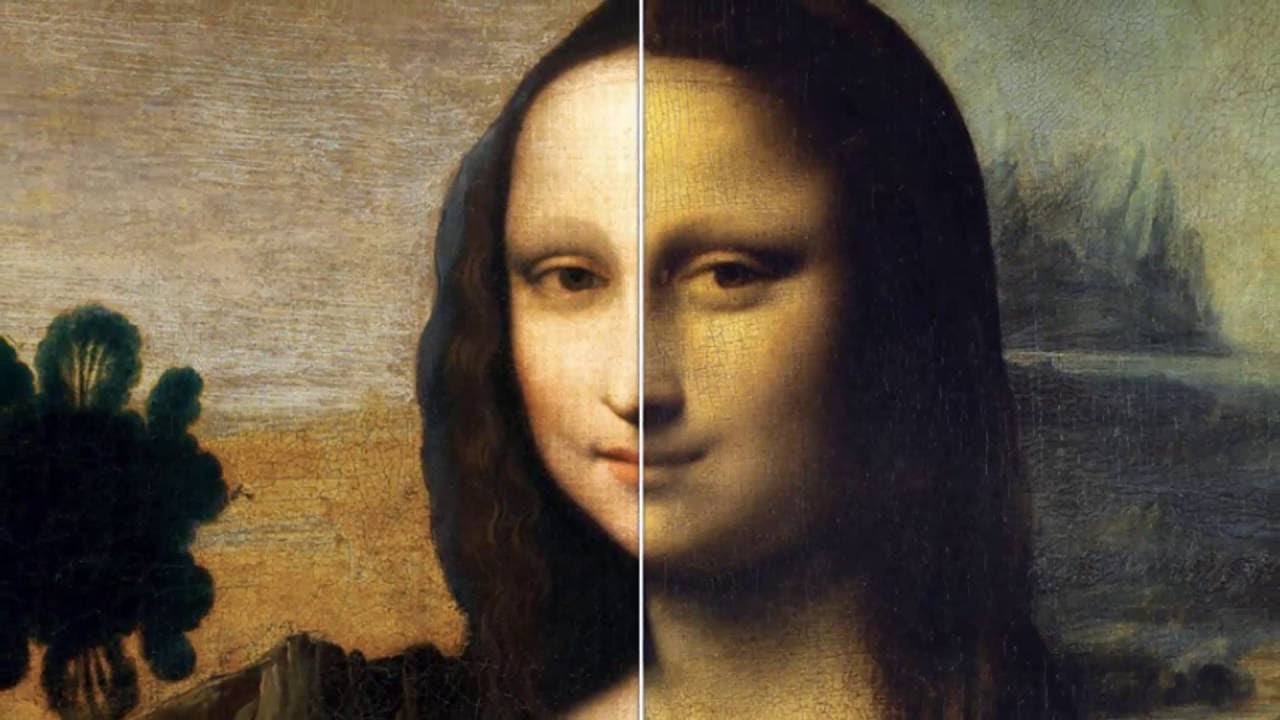

The Isleworth Mona Lisa, left, and Leonardo da Vinci’s original masterpiece. Courtesy of the Mona Lisa Foundation.

In addition to the dispute over the painting’s ownership, there is also the matter of its authorship. Although the Mona Lisa Foundation has worked for years to prove that the second work is also by Leonardo’s hand—and some studies in peer-reviewed journals make that case—others remain unconvinced. Leonardo expert Martin Kemp, for instance, has been outspoken in his belief that the work, which is said to depict a younger version of the Mona Lisa, is not by the Renaissance master, but a copy.

When he reviewed the Mona Lisa Foundation’s research on the painting in the book Mona Lisa: Leonardo’s Earlier Version, Kemp wrote on his blog, “The piles of unstable hypotheses, stacked one on another, would not be acceptable from an undergraduate.”

Stanley Feldman, principal author of the book “Mona Lisa: Leonardo’s Earlier Version,” during the unveil event of the “Isleworth Mona Lisa” on September 27, 2012 in Geneva. Photo courtesy Fabrice Coffrini/AFP/GettyImages.

The family that Protti and Marinello represent, who wish to remain anonymous, allegedly inherited their share of the Isleworth Mona Lisa from Leland Gilbert, a porcelain manufacturer. He had purchased a stake in the work from the British art historian Henry Pulitzer, whose 1966 book Where Is the Mona Lisa? introduced the heretofore unknown copy of the masterpiece to the world.

Pulitzer left his majority share in the work to his partner Elizabeth Meyer, who died in 2008. That’s when the international consortium entered the picture, forming the Mona Lisa Foundation to try and prove the painting’s authorship.

“Our clients had a very close relationship with the painting and Elizabeth Meyer,” Protti said. “The trouble started after her death.”

The Isleworth Mona Lisa, possibly a second version of the painting, also by Leonardo da Vinci. Courtesy of the Mona Lisa Foundation.

The Mona Lisa Foundation did not respond to inquiries from artnet News, but a representative of the foundation, Markus Frey, told the Art Newspaper that the claim from Gilbert’s heirs was “ill-founded and has no merit.”

Since 1975, the painting has spent most of its time locked away in a Swiss bank vault, emerging in 2014 for a show in Singapore, and later in Shanghai in 2016. Last month, it returned to public view in Europe for the first time in decades when it went on display at the Palazzo Bastogi, from June 8 to July 30.

A hearing has been scheduled for September 8 in Italian civil court. The Gilbert heirs hope it will provide an opportunity to learn how the painting was imported to Italy for the exhibition, and to try to keep it from being exported. “What we ask the court is to keep the painting here in Italy,” Protti said. “Our clients would like to make sure that the painting does not go back in the vault for another 40 years, because it’s important to the public. They want the public to know and to be able to see this painting.”

“When you own a painting like this, you are a custodian of a treasure that is the property of humanity,” he added. “The owners have a huge responsibility.”