The artist Seth Becker got lost in the Natural History Museum after hours one night when he was a kid. He told me the story as he stood in front of Antoine’s Tiger, his painting inspired by Ming of Harlem, a tiger who was discovered living in a New York City apartment in 2003—another formative childhood memory for the artist. The painting is one of over two dozen roughly notebook-size oil-on-panel compositions now on view in “A Boy’s Head” Becker’s solo debut at Venus Over Manhattan (on view through March 9) in downtown Manhattan.

Seth Becker, Antoine’s Tiger (2023). Courtesy of the artist and Venus Over Manhattan.

“In high school, I was taking a drawing class after school at the Natural History Museum. One day the class went late and by the time I was leaving, the museum was closed,” Becker explained “The lights were off in most of the galleries, and I couldn’t find an exit. I went into the Hall of Biodiversity because I knew how to get out of the museum from there, but I forgot about the Bengal tiger. It was dark, and I turned around and it was right there. It was one of the scariest moments,” he said.

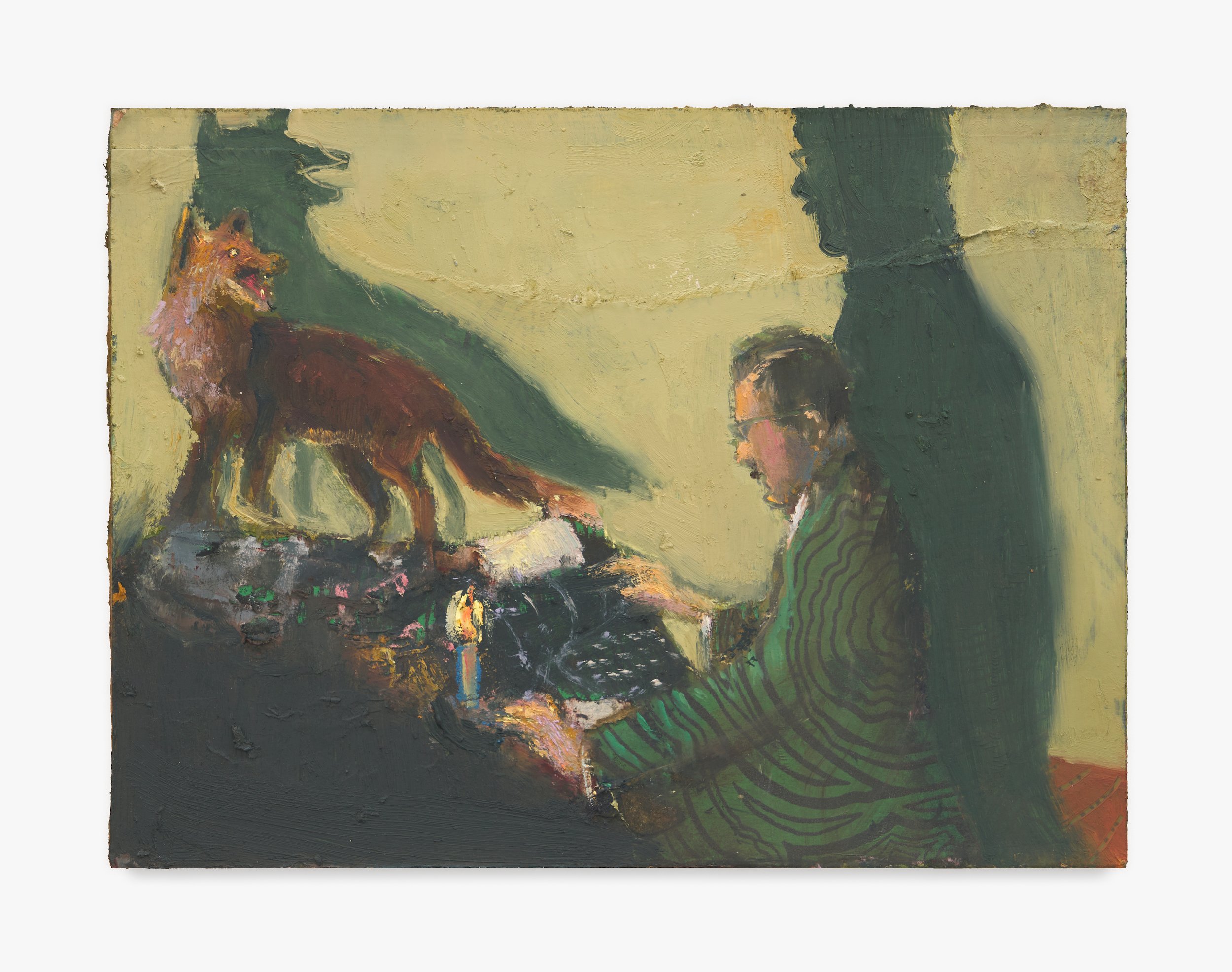

Seth Becker, Painting by Moonlight (2023). Courtesy of the artist and Venus Over Manhattan.

The story is one many Becker shared as we walked through his exhibition. While one or two were about him, most were stories from books of fiction or history or books about painting and artists, and shared with a contagious sense of curiosity. The artist, who was raised in Queens, now lives in Wappinger’s Falls, a town in upstate New York, with his partner Rachel, and their dog. He has devoted much of his life to books and their contents. During the day, Becker. works as a librarian. He paints during the evening hours and into the night, in a studio he keeps in the attic of their home.

In some ways, Becker’s work explores amorphous spaces between the worlds of fiction, history and the present. The paintings in the exhibition—which all date to 2023— are tender, melancholy, imaginative, sweet, and strange all at once. “A Boy’s Head” is a follow-up to Becker’s work’s inclusion in Venus Over Manhattan’s 2022 exhibition “Small Paintings.” All of his paintings are inspired, in some capacity, by vernacular 19th-century postcards that he collects. These postcards are uncanny and disconnected snapshots of a bygone world, which offer a framework from which Becker invents, adds, experiments, and most importantly imagines.

Portrait of Seth Becker. Courtesy the artist and Venus Over Manhattan, New York.

“I don’t work in terms of groups—one painting just comes out of the last,” Becker explained. He named the show after a poem by Miroslav Holub, “A Boy’s Head” which celebrates the limitlessness of imagination.

“Looking at the work together, I thought the poem spoke to a lot of the themes that I’m interested in. Wonder is the word for what I’m after and it’s what I’ve been pursuing for a long time.”

Circus scenes, pastoral landscapes, artist’s models, and, most of all, animals pop up again and again throughout these works. Dogs, horses, and tigers stand in as innocent avatars witnessing the world alongside humans (Becker’s creatures possess a great sense of pathos).

Seth Becker, Acrobat (2023). Courtesy of the artist and Venus Over Manhattan.

These repeating motifs are purposefully employed, hinting at an interconnectedness between the discrete compositions. For instance, in one painting, Acrobat, a performer in a dazzling robin’s-egg blue hue costume contorts her frame. This acrobat’s ensemble reappears in The Acrobat Reveals Her Birthmark in the Shape of a Rabbit, in which we glimpse a birthmark in the shape of a hare on the woman’s back. That rabbit itself pops up once more in Weathervane, as the shape of a weathervane atop a barn. Sometimes a distinct color unites separate works, instead— the robin’s-egg blue of the performer’s costume is invoked in the foreground of Painting By Moonlight, where a nude model stands before an artist with their easel, amid a nighttime forest.

Seth Becker, Batman’s Living Room (2023). Courtesy of the artist and Venus Over Manhattan.

Becker’s paintings are highly considered compositions of color and tone (he talks about having a revelatory moment in graduate school when he saw Bonnard’s paintings in black and white and came to understand the tonal scale). Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, Giorgio Morandi, and the contemporary Scottish painter Andrew Cranston are all influences. One work, Watteau’s Skull is an homage to another of his greats.

But, for all their rigor, the paintings can be funny, too. “Humor is something I am just now letting myself do. I tend to be very serious. I decided why not put in Batman, the most serious superhero in my work, and I’d imagine him coming home drunk,” said Becker. The resulting painting— Batman’s Living Room—shows the superhero leaning against a corner, the two walls covered in peeling wallpaper—literally. “We had a book of wallpaper samples in our house. There were all these amazing patterns, I decided to collage them on,” he explained.

Seth Becker, Magic Trick (2023). Courtesy of the artist and Venus Over Manhattan.

Often these images play on small tricks of the eye. In Poet at Work, Becker paints on a piece of wallpaper itself, and the patterns of the paper form the psychedelic pattern of a coat worn by a poet at his desk. In another work, we’re presented with either two dogs sitting close together or a two-headed dog. It’s hard to tell. We see what we imagine we see, his works seem to say. The painting Magic Trick had me looking again and again. In the work, a dog stands on its hind legs in excitement, casting its shadow onto a white sheet. A woman holds up the sheet like a curtain, and with party decorations visible, it seems as though a hidden surprise is about to be revealed. For a moment, the dog’s shadow seemed to me to transform before my eye into the shape of the Victory of Samothrace, before returning to the shape of a canine. This painterly illusionism is something Becker’s paintings do well—provide the mind with a space to imagine lifetimes of possibilities occurring somewhere else.

“I love the idea of people seeing my paintings in a book,” Becker told me, as I left the gallery. “I want people to see each work one at a time and to be in the world that exists in each one.”