Political discourse in 2018 often feels less like a good-faith debate than like a winner-take-all bloodsport, especially here in Donald Trump’s America. In that sense, it’s fitting that someone would look to one of history’s most violent athletic competitions for instruction on how to navigate the civic gauntlet. But in Primitive Games, a performance debuting tonight at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, multidisciplinary artist Shaun Leonardo is taking this tack in a (literally) disarming way.

Commissioned by the Guggenheim’s Social Practice initiative, Primitive Games attempts to resolve a divisive political debate through movement alone. Leonardo has coached participants to express themselves using actions inspired by the ancient Italian sport calcio storico (“historical football”), an aggressive blend of rugby, soccer, and borderline gladiator combat. Although the game is so riotous that Florentine officials banned it for a year after a 50-player brawl exploded mid-match in 2006, the artist hopes he has found a way to use calcio storico to actually de-escalate tensions.

Speaking to artnet News, Leonardo explained that, when he originally discovered the game, he was actually drawn in by what preceded the inevitable melee. “What was so compelling to me was that, because of the sheer amount of violence—or I should say the possibility of violence—so little happens at the beginning of the game,” he says. “It just becomes this beautiful mirroring exercise” in which each of the players on the court tries to size up his counterpart’s body language to gain an initial advantage. (Just think of the way boxers tend to start a round by circling one another, bobbing, rather than immediately throwing haymakers.)

What Leonardo describes as an “eruption of violence” soon overtakes this introduction. “And so what I started to do,” he explains, “is to simply ask myself, ‘Well, what would this game look like if I extracted all the violence, and just analyzed the body mechanics?’”

Participants at a workshop for Shaun Leonardo’s Primitive Games, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2018. Photography by Giacomo Francia. Courtesy of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

The Games We Play

The result is Primitive Games. Leonardo has been preparing four different groups of participants for the public performance through a series of workshops dating back months. Their efforts behind closed doors will culminate in a wordless debate at the Guggenheim about a highly charged sociopolitical issue—one that Leonardo has chosen to keep secret until the performance begins.

Each group bears a different but intimate relationship to the issue. If the subject were abortion, for example, the groups might include Planned Parenthood employees, protesters of abortion clinics, women who have ended pregnancies, and evangelical Christians. Debating climate change might bring scientists, policymakers, coal miners, and hurricane survivors into the arena. During the workshops, Leonardo has coached the participants to consider how their unique experiences translate into their body language, particularly during moments of conflict.

At the start of the event (which Leonardo calls a “ceremony”), the groups will merge into two teams via their nonverbal responses to a series of questions the artist poses. From there, every participant will confront one of their counterparts on the opposing team. The two sides will engage each other through gestures originating from three options sourced from calcio storico—options that Leonardo has dubbed “mirror,” “shatter,” and “deflect.”

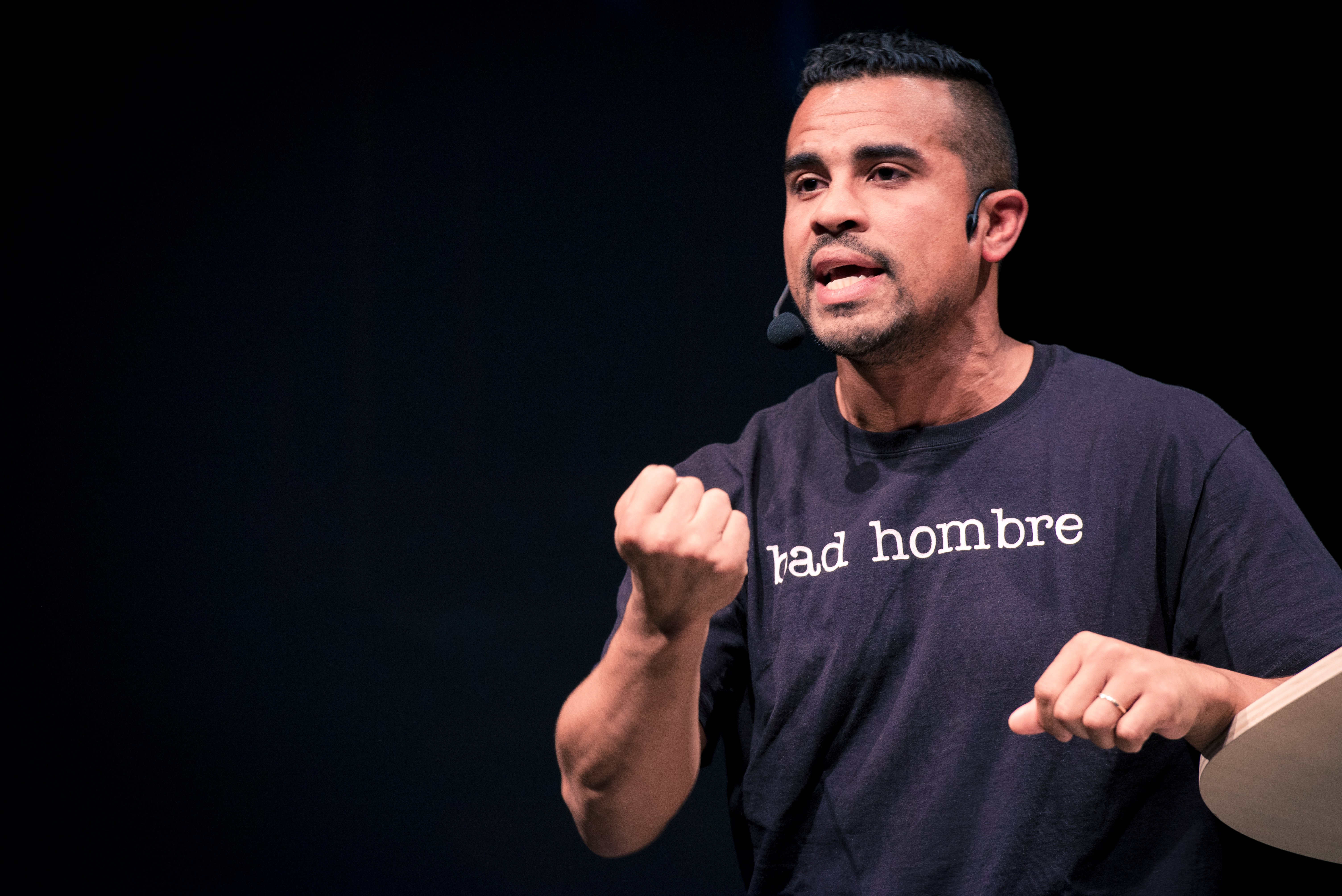

Shaun Leonardo, I Can’t Breathe. Courtesy of SVA.

The Call of the Arena

It isn’t just the public who is uninformed about the identity of the central issue and the four competing groups. Not even the participants themselves have any understanding of who they will be facing off against outside their own constituency, let alone over what subject. And for Primitive Games to function as Leonardo hopes, those answers must remain hidden until the moment the performance begins.

The reason, in Leonardo’s view, owes to the way our political discourse has devolved from an earnest (if complicated) conversation into a series of prejudicial defense mechanisms. To debate an issue in contemporary times is to forge your talking points into sledgehammers in advance, then try to beat your opponent into submission with your carefully crafted words as soon as they move to present their side of the story.

“So much of that language is formulated based on who you already perceive your opponent to be,” Leonardo says. “I feel that is precisely what has worsened in the last five to 10 years [of political life]: this need, this desire to prove oneself right, not allowing for communication to take place. And so much of that stems from fear—a fear of letting go of a worldview that has provided security.”

In this context, he suggests, it isn’t a shock “that the needle hasn’t moved on any of these issues, because there is no meeting ground.” And after encountering calcio storico in this climate, Leonardo began to notice that the players’ physical strategies paralleled political partisans’ debating strategies.

For example, brandishing the same ugly language as your opponent, sinking the debate deeper into the muck? Mirroring. Trying to win an argument by simply talking over your opponent, or shifting away from the central issue to a personal attack? Shattering. Responding to a relevant question by answering an alternate one that was never asked? Deflecting. Think of it as rhetorical trench warfare.

In that sense, Primitive Games contests the notion that solving our most virulent political problems requires more conversation. “My argument is that the body often conveys more truth than words capture,” Leonardo says. “So if we can more carefully read how our bodies move during these times, during these experiences, these memories of conflict, how is it that we can use that skill to better read someone that we’re perceiving to be ‘other’?”

Leonardo teaching a public program at Recess on a recent Saturday. Courtesy Recess.

More Than Words

Primitive Games is hardly the first project in which Leonardo has explored body language as a communicative tool—and often times, an unconscious storage system for a counterproductive narrative about oneself or one’s world. He also runs the arts diversion program at New York nonprofit Recess, where young people convicted of misdemeanors can potentially have their charges dismissed (as well as their cases sealed) for successfully completing a four-week cycle of arts education in lieu of traditional legal penalties.

In partnership with Brooklyn Justice Initiatives, Leonardo uses the Recess curriculum (developed with fellow artists Sable Elyse Smith and Melanie Crean) to help entrants to the program, in his words, “better analyze their stories through performance to dispel the way they are already defining themselves as criminals.” And although Recess exists as a place of possibility and re-definition, Leonardo also acknowledges that it is only temporary.

Ultimately, even though the program can aid participants by insuring their initial charges never appear on their permanent records, “they’re going home to situations that compound all of the issues” that put them at risk in the first place: a flawed education system, poverty, problematic home environments, violence, and more. Even if Recess graduates successfully reframe their stories in the program, their next chapters remain unwritten.

Although the stakes for Primitive Games are lower than for Leonardo’s work at Recess, both projects share this element of open-endedness. When asked how the Guggenheim contest will resolve, the artist admits he does not know. “We’ll feel it out,” he says. “I think mental strain and physical exhaustion will all play a role in how it ends.”

But Leonardo definitely knows what he hopes to achieve at the Guggenheim. Aside from the “direct objective”—namely, moving participants and audience members alike closer to true engagement with others through clearer understanding of body language—the artist has a higher objective for all involved.

“The loftier goal is that these individuals understand that they are not defined by their affinities, by their affiliations, and that there is much more meeting ground” on important issues, he says. “And what that means is that a space is gained in which they might start to listen. And if I can prove that [happens], then I feel like the work might be able to have impact in a lot of different communities.”

“For me, it’s never a singular performance,” says Leonardo. “I’m trying to create a model that might be useful.”

Shaun Leonardo’s Primitive Games will take place at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, on June 21 at 7 p.m.