Simon Starling Nine Feet Later, (2015)

Photo: courtesy Backlit

Two texturally distinct venues house this informal mid-career retrospective of Simon Starling’s work: the sleek, purpose-built Nottingham Contemporary and Backlit, a post-industrial artist-run space some fifteen minutes distant by foot. Some quarter century into his career, and eleven years after he won the Turner Prize, this is Starling’s first such major institutional show in the UK. It’s an anomaly perhaps explained by the curious status of the material that he offers for exhibition.

In a number of instances, the objects displayed are arguably not artworks per se, but their associated debris. As visitors to a Starling exhibition we are at times offered the material remains of a sequence of labors: the charcoal shards of a boat and some pieces of fishing tackle in Blue Boat Black (1997), for example, or a group of four silver bowls and a wooden mold in A silver bowl… (2013).

Together, both venues investigate arenas of enquiry revisited by Starling over the last two decades: the history of photography and the moving image, the evolution of automated production and computing technology, and the impulses and conditions through which materials are transformed by human labor.

Just as the labor sequence of plowing, irrigating, growing, harvesting, refining, bleaching, weaving, dying, stitching, and transporting cotton is invisible to the purchaser of a £2 T-Shirt, so the processes by which Starling comes to present us with objects take place out of sight.

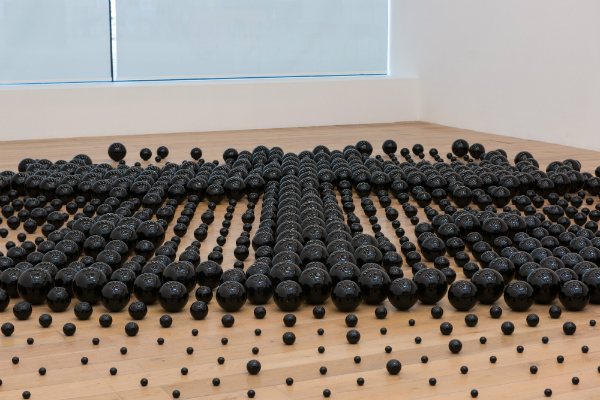

Simon Starling The Nanjing Particles, (2008)

Photo: Hugo Glendinning, Courtesy the artist, MASS MoCA, North Adams and the Private Collection Jacques Séguin, Switzerland.

The Nanjing Particles (2008) occupies the gallery as small nineteenth century photos showing Chinese workers at a factory in Massachusetts and two large blobby stainless steel sculptures.

The journey from one to the other speaks of the transformation and migration of manufacturing over the last century and a half. The Chinese workers offered cheap unskilled labor in the nineteenth century in an area of the US long since departed by heavy industry and now associated with scientific and technological research. Starling commissioned a local lab to create 3D images of silver particles from the original photograph. These were then sculpted as stainless steel models one million times the original size in Nanjing, China, and shipped back to Massachusetts for exhibition.

None of this is apparent without reading the accompanying text: a proviso that might otherwise give one pause, but which here seems rather the point. We should want to know about the conditions and forces behind the manufacturing of all manner of things, but we rarely do, perhaps because their provenance has been obscured, or because it is convenient for us not to probe.

Project for a Rift Valley Crossing (2015-16) is unfinished, a status that, perversely, permits the work a comparatively resolved shape: a simple canoe cast from magnesium derived from 1,900 liters of the Dead Sea. A solid object formed from a liquid. Starling will return the boat to its source at the close of the exhibition in June and attempt a crossing of this geopolitically charged body of water. Quite what transformation either Starling, or the boat, will undergo en route will provide the work’s final act.

Simon Starling, Red, Green, Blue, Loom Music

Photo: Sebastiano Pellion di Persano, Courtesy the artist and Galleria Franco Noero.

Not all of Starling’s output shares this shard-like, archeological quality. Red, Green, Blue, Loom Music (2015-16), at the heart of the Nottingham Contemporary show, is an elegant and satisfying work in three parts. The first is a film of an early automated ribbon and trimmings factory in Turin, which is beamed out of a three color projector. The ancient machines bob and dance, producing a rhythmic clatter as they weave. The projection pauses on three spools of silk—one in each of the colors beamed from the projector—then in a moment of pure theater, sprightly piano music pours from an adjacent space separated by a curtain of threads.

The tune echoes the dance of the machinery, which was in turn weaving a three-color visual rendering of the music. Framed on the wall of this second space, the notched cards of the jacquard looms display a striking resemblance to the paper roll that feeds through the pianola, and both to the punched tape used in early computing (itself the subject of Starling’s 2009 work D1-Z1 (22,686,575:1)).

The equally Ouroboros-like Black Drop (2012) is the centerpiece of the smaller exhibition at Backlit. On one level this 35mm film illuminates the role astronomers played in developing the moving image in their attempts to capture the transit of Venus across the sun: the titular “black drop.” Incorporating 35mm footage of the Transit of Venus in 2012, the film also documents its own production, capturing spooling and slicing in the editing suite that makes the materiality of physical film inescapably evident. (With satisfying kismet the star-gazing voiceover was provided by Peter Capaldi, shortly afterwards anointed as Dr Who.)

Simon Starling, La Source (demi-teinte), (2009)

Photo: Hugo Glendinning © Simon Starling, courtesy neugerriemschneider, Berlin.

Questions of making and automation are apposite for a city that gave us the term “Luddite” after early nineteenth-century factory workers opposed the introduction of machinery that threatened their jobs. Memories of Nottingham’s once central role in the textile industry live on in the names of streets and pubs: Nottingham Contemporary has a lace pattern imprinted in its concrete façade and Backlit is housed in a former textile industry. Starling studied photography here in the late 1980s, and his success as an artist associated with the city seems to be held as totemic: evidence that creative industries might flourish where manufacturing has largely died out.

The one off-key element in the show is Joseph Wright of Derby’s late eighteenth-century painting The Alchemist brought across from Derby Museum. A daguerreotype of the work by Starling rests in its original place—presumably to share the sprinkling of artist fairy dust across other local institutions. It’s not an easy time for small museums in the UK—troubling closures and loss of collections abound—but coopting associations with contemporary art in this way too often muddies expectation in either direction, doing neither the artist nor the collection any favors.

“Simon Starling” is on view at Nottingham Contemporary and Backlit through June 26, 2016.