Enigmatic to the core, the late Bruce Chatwin was at his best when ambling around on the hunt for Brontosaurus bones in Patagonia. He would later be accused of making up many of the interviews and experiences in his iconic travel book In Patagonia, but by then Chatwin had established himself as a charismatic writer, and would go onto write several adventure books and novels. One of those novels, The Viceroy of Ouidah, was adapted into the film Cobra Verde by Werner Herzog, and Chatwin and Herzog became friends. In Herzog’s new film, Nomad: In the Footsteps of Bruce Chatwin, Herzog ruminates on their friendship, and re-enacts some of the trips that Chatwin took in what the director calls “an erratic quest” to get to the heart of who the man was.

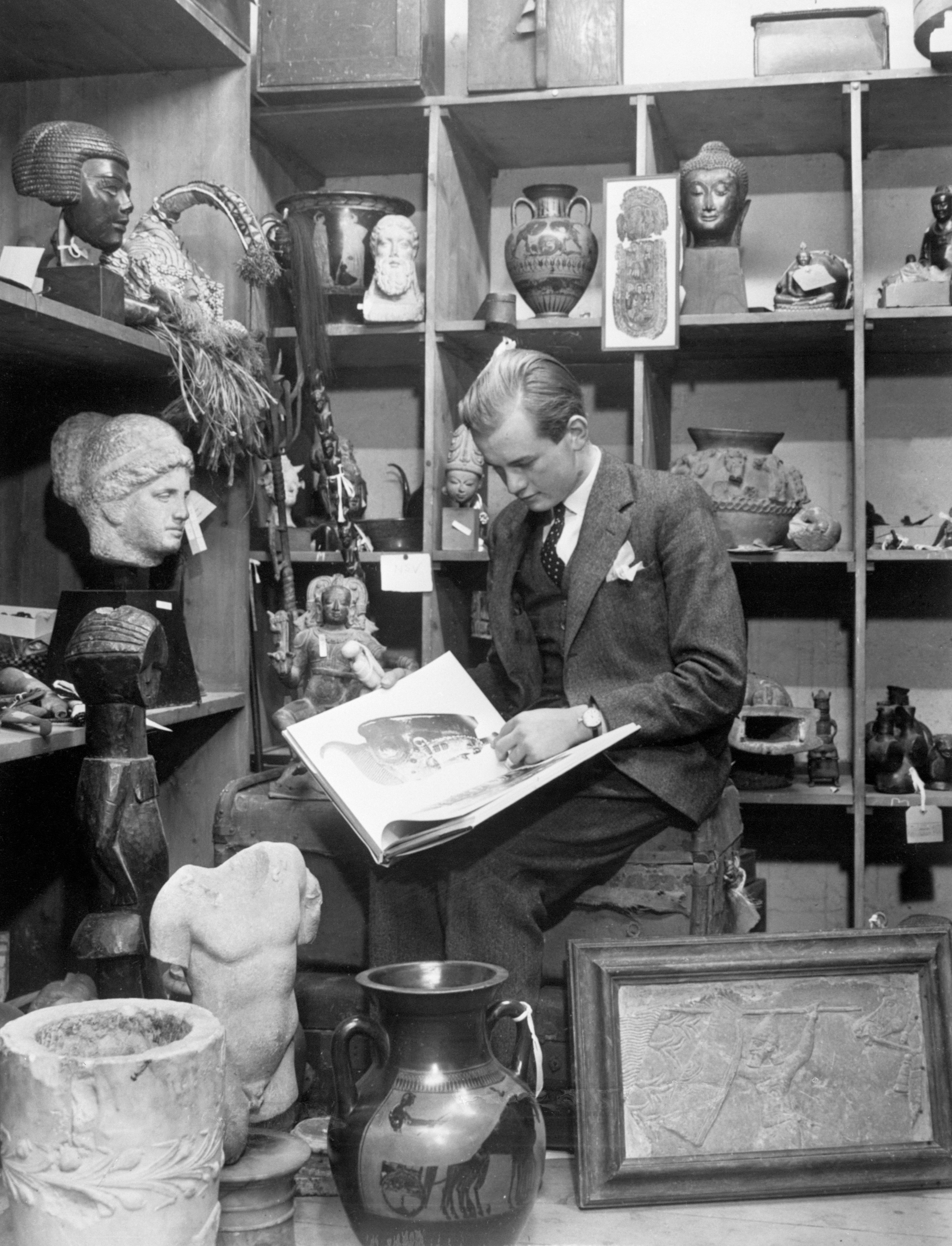

No story about Chatwin is complete without his connection to the arts. Before Chatwin became a travel writer and novelist, he was an art specialist at Sotheby’s. According to his biographer Nicholas Shakespeare, Chatwin began as a lowly porter in 1958 before moving into the antiquities and Impressionist art departments as a cataloguer. There, he developed an eye for spotting forgeries, and quickly moved up the ranks, becoming an expert in both departments.

Bruce Chatwin with writer Jorge Luis Borges (left) on the BBC television series ‘Frank Delaney’, October 1983. Photo by Chris Ridley/Radio Times via Getty Images.

Chatwin was sexually fluid. According to Shakespeare, the then-director of Sotheby’s supposedly used Chatwin’s attractiveness to both sexes to the house’s advantage when it came to convincing the rich to sell their art collections through Sotheby’s. In any case, he had mixed feelings about his role. Another biographer, Nicholas Murray, wrote about his frustration with being an appraiser. “In the end I felt I might just as well be working for a rather superior funeral parlour,” Chatwin said. “One’s whole life seemed to be spent valuing for probate the apartment of somebody recently dead.”

Chatwin would later go onto become a director at the auction house, though only at a junior level. This lower position further rankled Chatwin, and he became embittered towards the auction house’s shadier dealings, including the controversial deaccessioning of archaeological objects from the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, England. In June 1966, three months after he became director, the then-26-year-old Chatwin resigned.

Chatwin in May 1984. Photo by Ulf Andersen/Getty Images.

He would go on to become an art and architecture writer at the Sunday Times Magazine, where he would pen pieces on Russian art collectors, art theorist André Malraux, and Irish architect and designer Eileen Gray. The latter would become important in Chatwin’s life; during his interview with Gray, he noticed a map of Patagonia, and told her he had always wanted to travel there. “So have I,” she replied, “Go there for me.”

Thus began Chatwin’s most fruitful period of wandering—the focus of Herzog’s Nomad—but it wasn’t the end of Chatwin’s relationship to the arts. He would go onto have an affair with Robert Mapplethorpe’s lover Sam Wagstaff; according to Shakespeare’s biography, Chatwin was one of the only men Mapplethorpe photographed fully clothed. Chatwin would later write an essay in Mapplethorpe’s book, Lady, Lisa Lyon, which collected the photographer’s portraits of the famed bodybuilder.

Chatwin was diagnosed with HIV in the mid-80s—Shakespeare writes that Chatwin said he may have contracted it from Wagstaff—but continued to write. He passed away in 1989. One of his final works was the novel Utz, about a character named Kaspar Utz, a collector of Meissen porcelain; the character was based on Czech art collector Konrad Just.

In Nomad: In the Footsteps of Bruce Chatwin, Herzog travels to Patagonia and Australia (where Chatwin would embed himself with Aboriginal communities) to retrace his friend’s steps. There’s plenty of drama there, but sadly, the film doesn’t paint a full picture of the man’s wild career. It’s a shame: Chatwin’s adventures within the art world were no less fascinating.