The 20th century was a time of exceptional upheaval and major change in the art world. Many of the most influential art movements were born in this period—and extraordinary female artists helped lead the charge.

In honor of Women’s History Month, the Artnet Auctions team is celebrating the vital role and pioneering spirit of some of the most major female artists of the past 100 years. Read on to learn about three luminary artists whose works are live for bidding in 20th Century Art through March 30.

Niki de Saint Phalle, Magic Bird, 1981. Available now in 20th Century Art on Artnet Auctions. Est $20,000–30,000.

“Birds have been a major theme in my work; I think they’re free and spiritual. I hope if I get reincarnated I’ll get turned into a bird. I love their magic, their freedom.” — Niki de Saint Phalle

Looking as though it may take flight at any moment, Niki de Saint Phalle’s Magic Bird (1981) is an image of freedom, emblematic of the artist’s work in its color and fantastical nature. Aside from her sculptural female figures, known as “Nanas” (French slang for “chicks”), de Saint Phalle often depicted mythical creatures and animals.

Born in 1930 in Neuilly-sur-Seine to a well known aristocratic family, the self-taught artist first began making art as a form of therapy to process childhood trauma. She went on to become an important member of the Nouveau Réalisme movement that was taking shape in Europe. The movement also included Christo, Yves Klein, and Jean Tinguely; de Saint Phalle was the lone woman. She first began creating Nanas in 1964. Colorful, patterned, and crafted in a variety of shapes and sizes, these sculpted women embody spirits of celebration, power, and freedom just like Magic Bird’s.

A chronically under-exhibited and under-appreciated artist, de Saint Phalle’s body of work has been enjoying new recognition, spawned in part by the recent New York exhibition “Niki de Saint Phalle: Structures for Life” at MoMA PS1. Other recent major US exhibitions include “Niki de Saint Phalle in the 1960s” at the Menil Collection in Houston, which will travel to the Museum of Contemporary Art in San Diego next month.

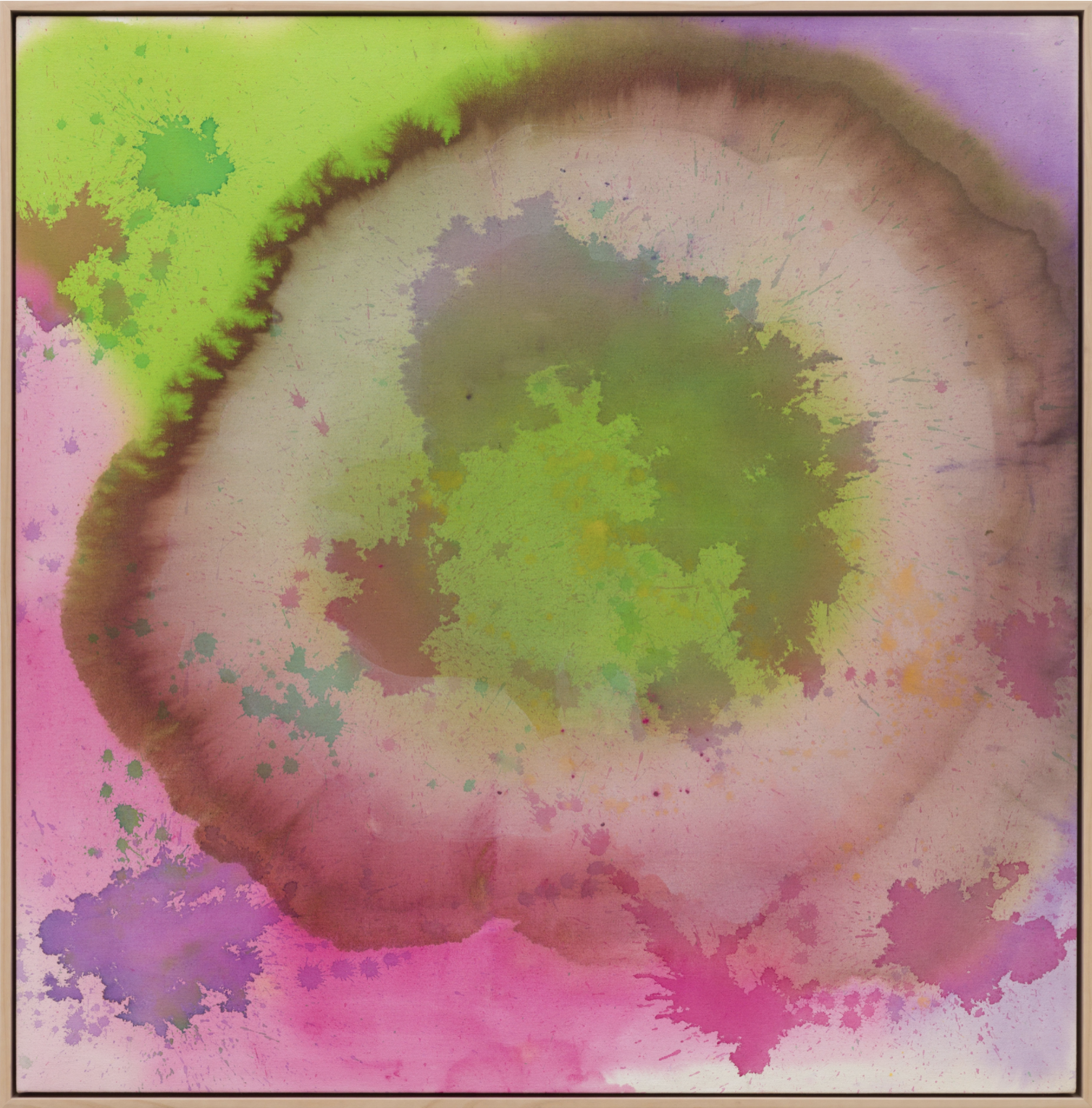

Vivian Springford, Untitled (VSF094), circa 1975. Available now in 20th Century Art on Artnet Auctions. Est $70,000–90,000.

“I want to find my own small plot or pattern of energy that will express the inner me in terms of rhythmic movement and color.” — Vivian Springford

Vivian Springford’s Untitled (VSF094) (circa 1975) shoots in diagonal, golden, teal, and gradient mauve patterns across her white cloth with galactic intensity. Its kinesthetic motion embodies Harold Rosenberg’s December 1952 essay “The American Action Painters,” which elaborated the physical bravura of abstraction.

Rose madder lake and cobalt violet pigments tell the story of Springford’s untouchable exuberance, despite the difficulties she faced as a female artist. In 1974 she entered Women in the Arts (WIA), the group that staged famous protests at the Whitney and MoMA to highlight gender underrepresentation. With a piece recently acquired by the Guggenheim Museum, Springford is now earning the international recognition she unquestionably deserved then. Almine Rech began representing her Estate in 2018, leading international markets for her cosmic compositions into new depths.

Berenice Abbott, Esso Station, Bronx, New York, 1936. Available now in 20th Century Art on Artnet Auctions. Est $5,000–8,000.

“It’s the juxtaposition of all this that is an intensely, immensely human subject. You’re photographing people when you’re photographing a city. You don’t have to have a person in it.”

—Berenice Abbott

Known for depicting the evolution of New York into a modern megapolis, Berenice Abbott was a pioneer of American documentary photography throughout the early 20th century. She worked under the Federal Arts Project as part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) throughout the Great Depression. In Esso Station, Bronx, New York (1936), Abbott captures an image of a gas station in the Bronx; the shapes of the pumps symbolize increased societal reliance on the technological developments of the time. After showing her project supervisors images from the Bowery in New York, Abbott was told that “nice girls don’t go down on the Bowery.” She responded, “Well, I’m not a nice girl. I’m a photographer. I go anywhere.”

Originally from Ohio, Abbott moved to New York in 1918, where she studied sculpture and connected with Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray. During her travels in Europe, she became an assistant to Man Ray in Paris, where she would have her first solo show in 1926. Man Ray also introduced Abbott to Eugène Atget’s photographs of urban France, which dramatically influenced her style. Upon returning to New York in 1929, Abbott found the city transformed, inspiring her to capture Changing New York, her best known series which includes Esso Station and images of newly built skyscrapers. In 1970, The Museum of Modern Art hosted a retrospective on Abbott, and her work has been collected by important institutions including the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington D.C., the National Portrait Gallery in London, and the New York Public Library.