The new big show called “State of the Art: Discovering American Art Now” at Crystal Bridges in Arkansas is a survey of contemporary art made by American artists who aren’t on the national radar even if they’re popular back home. The 102 regional artists (from 44 states) represented in the show aren’t slated to be the next national art stars, and that allowed the curators to relax into the task of creating a snapshot of work being made across the country without the pressure of winks to the international market or stroking the collective ego of the bi-coastal chattering class. One gets the feeling that for some of these artists, being included in this show will be a career peak. Which is absolutely fine. It’s refreshing to see such an expansive show entirely lacking in name dropping or bets on future auction prices.

It’s clear even from the press material that the show’s remit is simply to represent each region in the nation and be a people pleaser. As the curators walked the press corps through the 19,000 square-feet devoted to the exhibition yesterday morning, my sense was that that no one needs to have taken a single art history class to “like” every piece in it—everything is instantly gettable. Even the nod to Donald Judd made out of box fans and straw hats by Detroit’s Hamilton Poe doesn’t need the Judd reference to charm what I imagine will be the thousands of school children and Branson-bound travelers who will tour the show. (The fact that this museum, dropped in the middle of Walmart country, is a godsend to smart kids who would never otherwise be exposed to art is another story.)

Hamilton Poe. The automated fans made the appearance that the hats of dancing.

This is real art by real working artists. The populist bent was a considered choice. The exhibition’s curators, museum president Don Bacigalupi and staff curator Chad Alligood, traveled the country for nearly two years and visited about 1000 artist studios, and mostly avoided any truly challenging art; nothing here is willfully ambivalent or too subtle or dark. Almost every piece is turned up to eleven in terms of being engaging. Good examples this are the Mom booth, by Andy DuCett of Minneapolis, which will be staffed by real volunteer moms throughout the show’s run, or the knitted cave-like hallway that opens the show, by Brooklyn-based Jeila Gueramian.

Andy Ducett

Jeila Gueramian

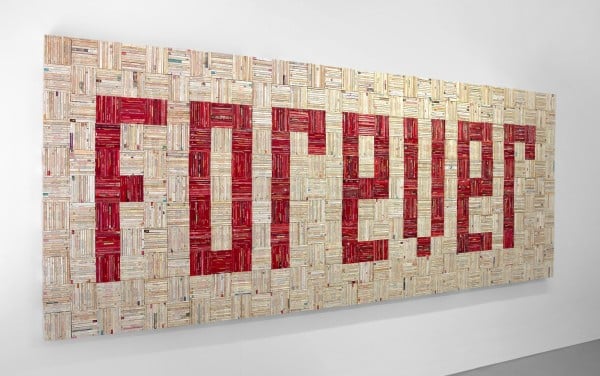

Even the political work has to be either charming or have a technical prowess that will impress the casual viewer. And there’s a preponderance of art that’s about clever or unexpected use of found items or common materials: a painting of an ox made with smoke, a wall piece made up of thousands of used romance novels, or a huge “painting” made from collaging thousands of discarded lottery tickets into a diamond pattern. Get it? Yes. Yes you do.

Exhibition curators Don Dacigalupi (L) and Chad Alligood (R) introduce the show during the press event.

The duo Ghost of a Dream made this work with used lottery tickets.

There’s not as much folk art in the State of the Art as I would have liked to see—most of the artists have MFAs from good schools—which is a shame, because folk art is some of the most likable art being made and is of course incredibly regional. The curators threw in a few self-taught artists, and they’re good, but the whole museum’s encyclopedic American collection seems almost allergic to self-taught art; maybe it feels too “coals to Newcastle” to the museum’s founder, Alice Walton, an heiress to the Walmart fortune. The museum’s home of Bentonville, high in the Ozarks (the region is undeniably beautiful), is also home to the Walmart Corporation, and it’s a semi-charming town, but the region feels a little spooky. Its stubborn ruralness has a whiff of meth hillbilly. As I walked and drove around town and dealt with my hotel’s front-desk people and gas-station cashiers and the like, I could sometimes hear the sinister banjo playing in my head. But Crystal Bridges could, with its money and location, be the best folk art museum in the world if it wanted to be, which it doesn’t.

Laurel Roth Hope, a self-taught artist from San Francisco, dressed up her wood carvings of common pigeons in handmade costumes of plumage of extinct bird species.

Vanessa L. German of Pittsburgh is a folk artist who makes “protection” figures for endangered children in her neighborhood.

Some quick facts about the show:

1) Despite the comparisons to the Whitney Biennial, this survey may or may not ever be repeated. They haven’t decided on that yet.

2) Crystal Bridges may or may not purchase any of the work from State of the Art for its own collection. They haven’t decided on that either, or won’t talk about it.

3) The show may or may not travel, as a whole or in parts.

4) All of the work in the show was made in the last three years.

5) The museum’s sizable endowment did not pay for this show. The money was raised independently by the show’s organizers.

The six Texas artists looked fine throughout, completely on par with the rest of the work. Chris Sauter’s science theme threatened to be too heady for the show, but still played the State of the Art game by being big and optically fun. Curator Alligood mentioned that a few American towns proved surprisingly fertile for interesting artists: Witchita, Omaha, Pittsburgh, and San Antonio were on his hot list.

Chris Sauter

Two of the most memorable pieces in the show for me were videos (and kudos to the curators for including a fair amount of video throughout). Susie J. Lee from Seattle made a Viola-esque triptych; it’s a digital portrait of three field workers in the fracking country of North Dakota. The extreme hi-def focus on their faces hooks the very human desire to study people’s expressions, and their exact line of work doesn’t matter much. They could be any often-overlooked laborers, like Walmart forklift operators or Tyson Chicken slaughterhouse workers, and the piece would still succeed, because these three subjects’ relationship with the camera is confrontational and a little unsettling. But it’s a good example of the kind of otherwise non-alienting political art the show favors.

Susie J. Lee

The other video that stood out for me was by Dave Greber of New Orleans. It’s projected as a big oval on the floor, like a rug or table top, and the bird’s-eye images of various objects in motion stack and layer and unfurl on top of one another in a relentless and exhilarating rhythm: fabric, plates, food, a dog, a cat, paint, everything plus the kitchen sink. It’s high-energy and hypnotic.

Dave Greber’s video on the floor.

Jonathan Schipper’s Slow Room.

And if I were to pick a “Most Likely to Suceed” in this yearbook, it would be an artist who already has broken out: Brooklyn-based Jonathan Schipper presents his piece “Slow Room.” His formula of annihilating big things (in slow motion) hits a lot of marks for what’s considered interesting and cool these days: the piece is a full-size installation of an old-fashioned living room, complete with all of your imagined old aunt’s brocade furniture and geegaws and upright piano and lamps and rugs, etc, though every single item is connected to a string that disappears into a hole in the wall. There’s a motor back there you can’t see but that over the course of four months will tighten the strings so that by the end of the exhibition every object will be pulled up and crushed against the wall, piled and broken. There’s a live camera feed of the progress available to home viewers. I have a feeling State of the Art will not be Schipper’s career peak. But it will be a highlight.

This post originally appeared on Glasstire on Friday, September 12, 2014.