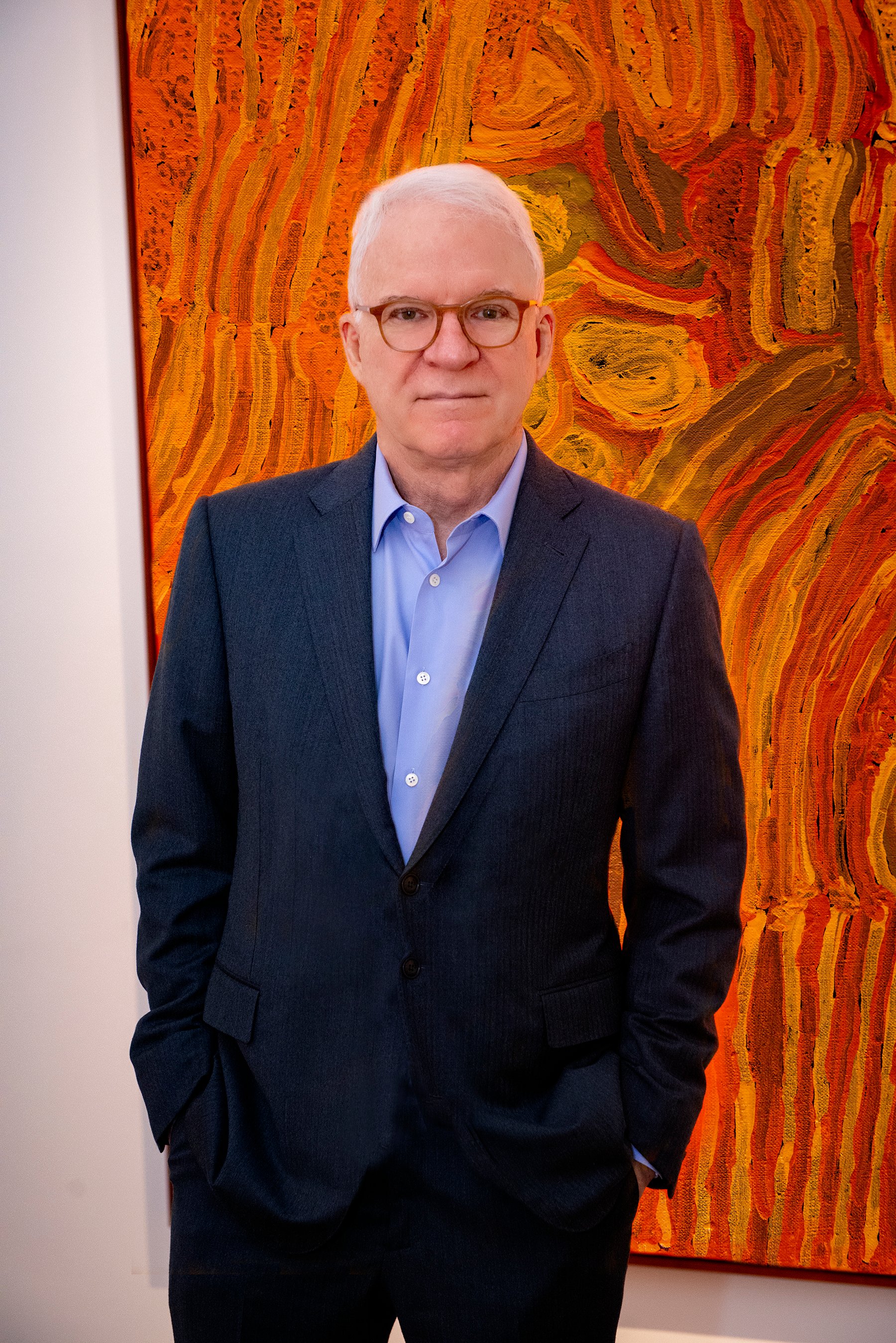

With a hand from actor, comedian, and noted collector Steve Martin, Gagosian is shining a spotlight on Indigenous Australian painters—which could mean big things for this sector of the art market. Martin and his wife, Anne Stringfield, are lending works of Aboriginal art from their personal collection to a show at Gagosian’s Upper East Side location that opens today.

“I never talk about our art collection, because it’s our private sanctuary, but I am so enthused about the Indigenous art,” Martin told Australia’s ABC, noting that he’s hung the Australian works in his collection alongside his paintings by Edward Hopper, Giorgio Morandi, and David Hockney. “There is no doubt these [desert paintings] hang well with others and that one day they will be in the company of great contemporary art at auction and not culled out as a special field.”

Martin’s love of art began decades ago—he bought his first painting, by American artist James Gale Tyler, at the age of 21. But his obsession with Indigenous Australian art is relatively new.

Four years ago, he saw a painting by Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri in a New York Times article about an exhibition of his work in New York. The artist was one of the so-called Pintupi Nine, a group of Indigenous Australians who had no contact with the modern world until 1984. By the end of the day, Martin had purchased one of the works in the show. It quickly became a prized possession.

Warlimpirrnga, Untitled (2013). ©Warlimpirrnga. Photo by Rob McKeever courtesy of Gagosian.

Now, that work is included in the Gagosian exhibition, which follows a small presentation that Martin staged in March for friends and family. At the gallery, his collection is joined by a work from the Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection of the University of Virginia.

Although none of the paintings in the show are for sale, it may still have a market impact. Martin is known for his interest in the Canadian Group of Seven, particularly Lawren Harris (1885–1970), who saw a substantial market bump when the actor curated “The Idea of North: The Paintings of Lawren Harris” with Hammer Museum in Los Angeles and the Art Gallery of Ontario.

The market for Aboriginal Australian art has has been somewhat tumultuous—it became highly sought-after in the run-up to the financial crisis, but tumbled during the market’s ensuing contraction. Now, says Gagosian director Louise Neri, who organized the show, the time has come for a re-assessment.

“Many recent art movements have been subject to economic speculation, in both local and international contexts. In 2008, the markets for modern and contemporary art suffered a dramatic temporary downturn, but regained robust momentum in the ensuing decade,” she noted. “Being an essentially localized market, Indigenous Australian art was left exposed in this downturn and was slower to rebound.” Since then, however, “a broader and more inquiring art market, with diverse appetites, has emerged.”

Neri, who hails from Australia, reached out to the University of Virginia after learning about their collection in the search for an early Emily Kame Kngwarreye to complete the show.

“It’s fantastic that Gagosian has elected to present this exhibition, but it doesn’t really surprise me,” collection director Margo Smith told artnet News in an email. She notes that interest in Aboriginal art has been growing in New York since Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri’s solo show at Salon 94 four years ago. The artist was also included in documenta in 2012 and was part of a larger traveling exhibition of Aboriginal work collected by Miami-based collectors Debra and Dennis Scholl in 2015.

Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Kame Yam Awelye (1996). ©Emily Kame Kngwarreye/Copyright Agency. Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, 2019. Photo by Rob McKeever courtesy of Gagosian.

A community of Indigenous Australian artists first developed in the 1960s, as result of the forced relocation of several tribes from the Western Desert to a settlement south of Alice Springs. The community was encouraged to paint, and a new art form sprung up, translating ancient traditions of sand art and body decoration onto canvas.

“Many people think Aboriginal art is only about traditional culture, without realizing these artworks are also deeply contemporary. They represent the culmination of years of practice by artists who have mastered a stunning visual aesthetic,” explained Smith. “Although some Aboriginal artists live and work in remote communities, they are actively engaged with the global art market.”

The exhibition includes canvases by the likes of George Tjungurrayi, Bill Whiskey Tjapaltjarri, and Yukultji Napangati, as well as Tjapaltjarri and Kngwarreye. The latter made headlines last year when observers noticed that Damien Hirst’s new series of “Veil Paintings” bore a striking resemblance to her work. But despite her elevated stature down under, few are familiar with Kngwarreye’s oeuvre outside of her native country.

“If you visit Australia, you’ll see contemporary Indigenous art in every major gallery and museum. But most Americans will never have that opportunity,” Smith said. “Steve Martin is a well-respected and knowledgeable art collector. That he has turned his attention to Indigenous Australian art could help many people overcome their initial reservations and take a deeper look. I think they’ll like what they see.”

See more works from the show below.

“Desert Painters of Australia,” installation views at Gagosian (2019). Artworks ©artists and estates. Photo by Rob McKeever, courtesy of Gagosian.

Naata Nungurrayi, Untitled (2010). ©Naata Nungurrayi. Photo by Rob McKeever courtesy of Gagosian.

“Desert Painters of Australia,” installation views at Gagosian (2019). Artworks ©artists and estates. Photo by Rob McKeever, courtesy of Gagosian.

George Tjungurrayi, Untitled – Kirrimalunya (2007). ©George Tjungurrayi. Photo by Rob McKeever courtesy of Gagosian.

Willy Tjungurrayi, Untitled (2001). ©Willy Tjungurrayi. Photo by Rob McKeever courtesy of Gagosian.

“Desert Painters of Australia,” installation views at Gagosian (2019). Artworks ©artists and estates. Photo by Rob McKeever, courtesy of Gagosian.

Naata Nungurrayi, Untitled (2010) ©Naata Nungurrayi. Photo by Rob McKeever courtesy of Gagosian.

“Desert Painters of Australia,” installation views at Gagosian (2019). Artworks ©artists and estates. Photo by Rob McKeever, courtesy of Gagosian.

Bill Whiskey Tjapaltjarri, Rockholes and Country Near the Olgas (2007). ©Bill Whiskey Tjapaltjarri. Photo by Rob McKeever courtesy of Gagosian.

“Desert Painters of Australia,” installation views at Gagosian (2019). Artworks ©artists and estates. Photo by Rob McKeever, courtesy of Gagosian.

Makinti Napanangka, Kungka Kutjarra (Two Women), 2001. ©Makinti Napanangka. Photo by Rob McKeever courtesy of Gagosian.

“Desert Painters of Australia,” installation views at Gagosian (2019). Artworks ©artists and estates. Photo by Rob McKeever, courtesy of Gagosian.

“Desert Painters of Australia: Works from the Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection of the University of Virginia and the Collection of Steve Martin and Anne Stringfield” is on view at Gagosian, 976 Madison Avenue, New York, May 3–July 3, 2019.