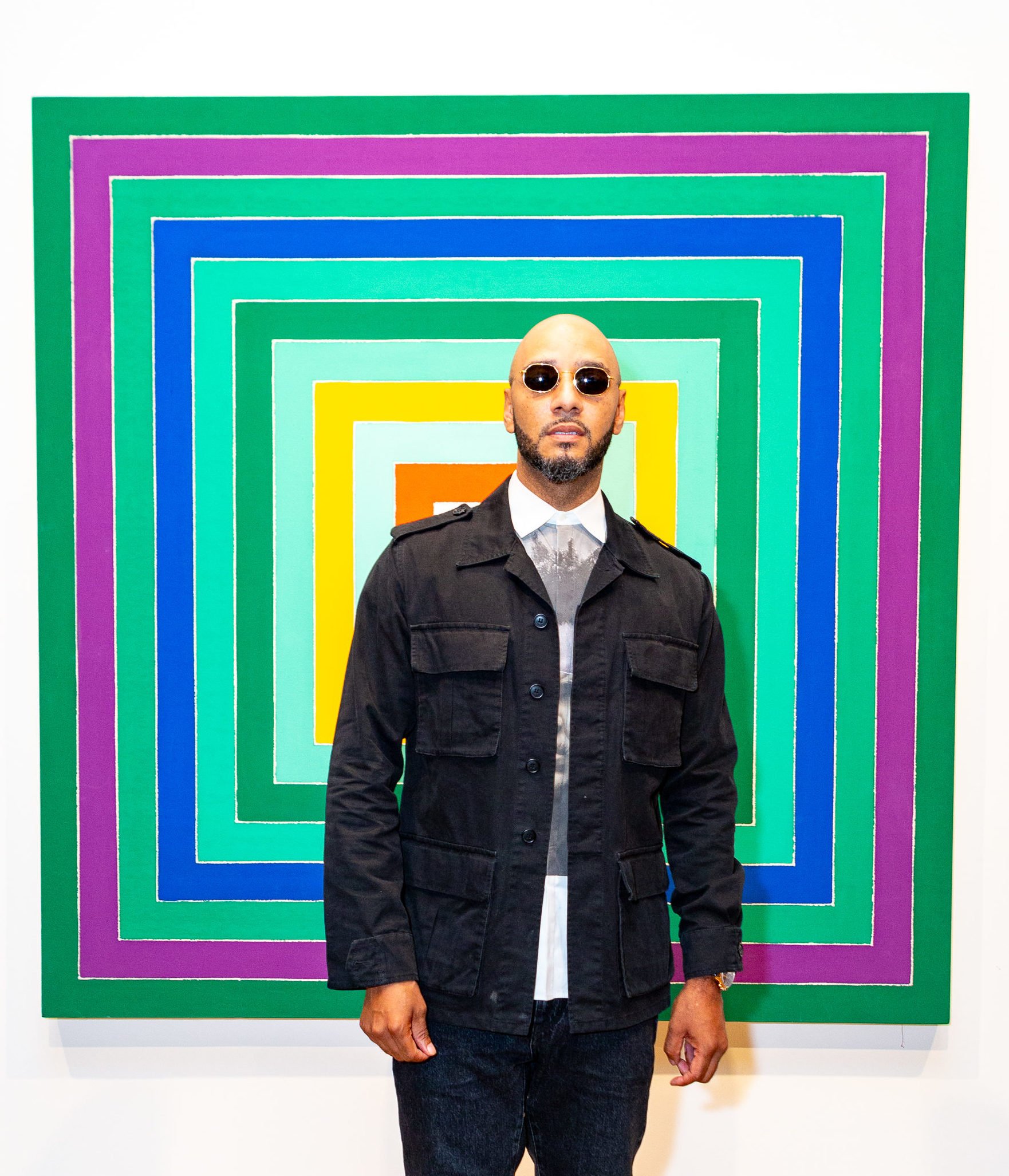

Earlier this month, appearing at the Bronx Museum’s gala to present an award to the artist Hank Willis Thomas, the music producer and art collector Swizz Beatz looked out at the crowd and repeated words of inspiration that have become something of a trademark: “The sky’s not the limit—it’s just the view.” His faith in boundless possibilities, which can be infectious, is well earned.

Growing up in the music industry—his uncles and aunt were involved in the Yonkers-based Ruff Ryders record label—Beatz first started producing tracks when he was 16, and had his first mega-hit the following year when he sold a beat to DMX that became the “Ruff Ryders’ Anthem.” Since then, he has produced chart-topping songs for Beyoncé, Jay-Z, Kanye West, Whitney Houston, and Bono; he even created a theme song for the New York Knicks. Today, he has a street named after himself in the Bronx.

Flush with early success, Beatz began collecting art at a young age—his first purchase was an Ansel Adams print at 19—and has since gone on to amass an enormous collection of work by both 20th-century greats and more recent stars like KAWS, Kehinde Wiley, and Nina Chanel Abney. Often buying art in tandem with his wife, the fellow Grammy Award-winning musician Alicia Keys, he says he is building a collection to leave in the care of his five children.

It’s safe to say that by the time that happens, the art field that Beatz has become a player in today will have been comprehensively disrupted—and it’s quite possible that he will have had a hand in that change. In the conclusion of a two-part interview, artnet News’s Andrew Goldstein spoke to the producer about where the art industry is headed, what his future museum is going to look like, and how auction houses should change the way they do business.

Jay-Z and Swizz Beatz performing together in New York City. Photo by Kevin Mazur, courtesy of Getty Images.

What are some lessons from the music industry that should be applied to the art industry?

The music industry was run by the same rules for so long that those rules kind of faded away over time, and people started coming up saying, “No, those are old rules.” I remember when Apple first came onto the scene, I was at [Interscope Records co-founder] Jimmy Iovine’s house and he said, “I was with my friend Steve Jobs and he was telling me that all your music is going to be on this thing.” He was showing me all the playlists and he said, “These guys are trying to do a 50-50 deal with me, and I don’t really know yet.”

Imagine if he had made a 50-50 deal with Apple at the time. I think all of those labels could have done 50-50 deals with companies that are now in power—deals that they still had to do anyway for much, much less. When Napster hit, somebody was supposed to say, “Let’s bring this thing in-house so we can figure out how to disrupt things together, because people are interested in it, and it’s obviously a flaw that you found in our system.” But instead, they went to war. So if the galleries do that, we already can see the future.

People have been talking about the “gallery crisis,” where galleries have struggled to figure out how to adapt their businesses to a globalized, digitized world where foot traffic is plummeting and the cost of doing business and chasing customers around the world keeps rising. But it seems the problem you’re trying to solve relates to the artists—that they’re not getting as much out of the deal as they should be. Do you think solving the gallery problem is critical as well?

Everybody is trying to learn. But they’re waiting for other people to do things first, and that’s where the problem is. Nobody wants to take the risk. It’s easy for me to do what I do because I’m not attached to those models. I’m not a dealer, I’m just an artist myself wanting to change things that we can all see are wrong.

Jay-Z started his is own streaming platform, and I know that you guys talk business. Is there anything that you learned from what he did that functions as a case study for what you’re trying to do?

It is a case study. Jay-Z took the risk, and Tidal is amazing. But still, we still need to support [it]. If Jay-Z came with Tidal, then everybody in hip-hop should be on Tidal. But it’s not like that—everybody is figuring out a reason to not be on Tidal.

The thing with Tidal was that it was an open space, and the competitors saw that, so when it came to anybody in power, competitors sniped them with money. We don’t realize that the currency isn’t always money—sometimes the currency is being a part of something that we own. That’s why we have so many problems, because we don’t own the things we want to change. So, here’s Jay-Z, putting up this Tidal thing, and everybody’s running from it.

The thing that the music and film industry had to help it transition to a new model is scale. The art world is tiny. Is that something that can change? Is that something that needs to change?

Technology is going to change that. Because nobody is walking into places anymore. People are used to being on their screens and interacting in a different way. It was important for me to start No Commission as something not in the virtual world, but in the actual world, where people can come in and understand it. But it’s going to be through technology that we give them the heads-up.

Nick Cave’s Arm Peace, 2018, was also featured in the “DREAMWEAVERS” show. Photo courtesy of UTA Artist Space.

How do you think Instagram has helped expand the population of art collectors in the world? It seems it’s had an important impact.

I figured out how to use Instagram for building awareness by accident. I had been thinking of using it to promote what I was doing in music or fashion, but never what I was doing in art. Then a couple of times I got excited about some artwork and I posted it, and tagged the artist in it, and they hit me back and said, “Man, thank you so much.” And I’m like, “Yeah, I appreciated the piece.” And they say, “No, my whole show sold out. I got galleries calling me. I’ve been doing this for a long time and you posted my piece and now I’m off to the races.”

I got another call, another call, and I thought, “This is powerful. We could free the artist through this. I’m going to give artists my platform to promote their work.” That’s how this thing took off—all from posting artists’ works on my Instagram and them selling out their shows. It seems people just watch my Instagram to buy everything that’s posted.

I’m curious, why are visual artists the ones that that inspire you? Why is that the constituency that you’re using your influence to help?

The art world is of a scale where we can make things happen. It feels more like a family; the music world is more like a business.

It’s interesting to think that the small scale of the art world makes it primed for disruption. Is there anything you can say about the tech platform you’re working on? I know in the past you’ve spoken about having the next phase of No Commission be a technological one, but also that you were thinking about opening a gallery. Is it all moving toward something?

I’m moving puzzle pieces every day, because every day things are changing. I’m just taking my time with it, to be honest. When I aim I want to hit the target, because it can’t graze you, it’s got to hit you, because it’s a bold move.

You’ve spoken before about how you think artist collaborations are the wave of the future—which is no surprise since collaborations are pretty much your stock and trade as a music producer, bringing multiple talents into the studio to record a track. The thing is, outside of famous outliers like Warhol and Basquiat, collaborations are really very rare among artists.

But wasn’t Warhol and Basquiat a great collaboration? I owned one of their works at one point, and that was back when I had braids in my hair—it was that long ago. I was able to afford it because the prices were so decent at that time, but I remember it was three times the size of a work by Warhol that was going for three times as much money, and I wondered why. Then I heard that it wasn’t accepted because Warhol was doing something with an African American. I was like, are you kidding me? I know what they were thinking: “You’re on top of your game, I’m on top of my game, let’s come together and do something.” But people couldn’t sell them—that’s how I got one.

I think the reason why people aren’t really collaborating that much today is because artists are really trying to lock themselves into a signature style, because there’s suddenly so much new competition. Before, there were just a few African American artists—now galleries are scrounging and scrounging. Like, “Does it look decent? Put him in there.” This is just supply and demand. It’s only going to get crazier.

Swizz Beatz, KAWS, and Alicia Keys. Photo: Clint Spaulding/PatrickMcMullan.

Do you ever encourage artists to collaborate?

Oh, all the time.

Do they ever do it?

[Laughs] They’ll do it for a commission from me, sometimes. But I know how imperative it is for everyone to be on their A game right now, because this is a life-changing point.

You’re on the board of the Brooklyn Museum, and you’ve also talked about the possibility of starting a museum of your own. Is that still in the plans?

I collect like I’m putting together a museum for my kids. That’s why I collect the large-scale sculptures and all that. And it’s going to have to happen, because there are too many works. But I want to build it in multiple places, so New York might be the photography side, and LA might be the sculptural side, and over here might be something else, so you almost need a roadmap to go see it. The Gordon Parks collection might be in one place, for instance. Because it gets overwhelming otherwise, and being on the board I see how much it takes to run one of these things, and how much it costs, and how big a space you need. So I’m like, “You know what? I want a lot of little satellites, but when they come together they create a big-ass museum.”

How do you divide your time? Do you put 50 percent of your time into art and 50 percent into music?

I’d say it’s 50 percent art and music and 50 percent business. Before, it was like 90 percent music and 10 percent business. But now I have to think business to make all the changes I think are needed. Why do I have to wait for someone else to move first? That somebody should be me. I can at least try.

The auction of Kerry James Marshall’s Past Times. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

One part of the art business you’ve spoken about is the resale market. You recently floated the idea of a process where a collector is offered the choice of ticking a box when putting a work up for sale to give a percentage of the proceeds to the artist, kind of like when you go to CVS and they ask if you’d like to donate money to cancer research. You’ve called it “the Dean’s Choice.” What has the reaction to that been?

It’s been good. If you don’t put the option in front of people, they’re never going to ask for it. Make it so the artists know who is really supporting them. With the Dean’s Choice, it’s the seller’s responsibility to protect the artist. A lot of people blame the auction houses, but who gives the work to the auction house? The person who bought your work!

So if I’m a fan of your work and I’ve made an investment 10 years ago and I’m making 500 percent off of that now, if someone were to tell me I can give three to five percent to the living artist—and you already know you’re going to make money off that piece—then I’m going to say, “Yes, of course,” and check the box. That’s my choice. Nobody’s forced to do anything, and it lets you give back to the living artist.

Sotheby’s is cool with it, because they’re already doing that in places in Europe. I figure in the first year of the Dean’s Choice, 20 percent of people are going to say yes; the second year, 30 to 40. And I think the numbers are going to keep going up, because if the artists are getting a piece of it then there would be a better relationship between everybody. It only takes one paragraph to fix it. We’re one paragraph away.