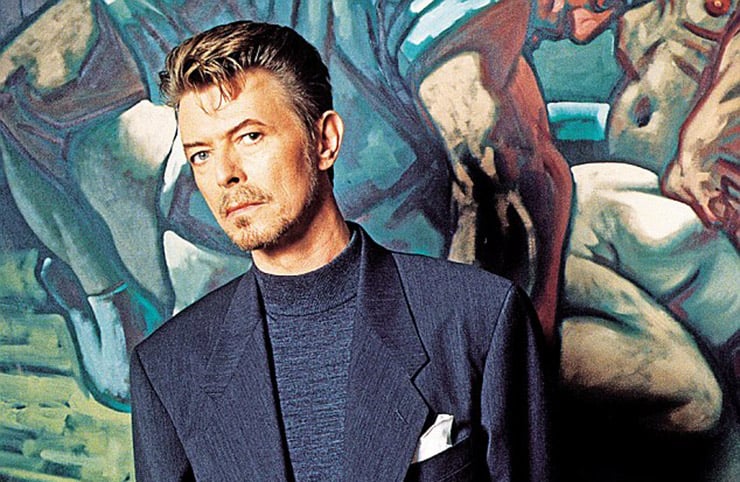

“Art was, seriously, the only thing I’d ever wanted to own,” legendary musician David Bowie, who died on Sunday, January 10 at age 69, told the New York Times in 1998. “It can change the way that I feel in the mornings.”

He went on to espouse his admiration for Frank Auerbach, David Bomberg, and Francis Picabia, and his appreciation of Marcel Duchamp’s sense of humor—although Bowie allowed that “there’s the other side of me that thinks he did it just because he couldn’t paint.”

David Bowie at the Berlin Wall, (1987). Photo: Denis O’Regan/Getty Images.

This love of art manifested itself in the music: As early as 1969, Bowie referenced Georges Braque in the lyrics of “Unwashed and Slightly Dazed.” “Joe the Lion,” released in 1977, pays tribute to a Chris Burden performance art piece with the line “nail me to my car and I’ll tell you who you are.” In 1974, Bowie based the set design for his Diamond Dogs tour in part on the work of satirical German artist George Grosz.

Bowie’s well-known love of fine art, however, has led to some exaggeration about the scope and breadth of his holdings. “Last week I was approached by a magazine about doing an interview on my ‘Surrealist and PreRaphaelite’ collection,” said Bowie in 2003, as recounted by Nicholas Pegg’s The Complete David Bowie (2011). “This was news to me.”

The set design model for David Bowie’s Diamond Dogs tour.

Photo: courtesy the Victoria & Albert Museum.

“Yes, I do have a (too frequently remarked upon) Tintoretto and a small Rubens… but the majority of what I have are British 20th century and not terribly big names,” Bowie insisted. “I’ve gone for what seemed to be an important or interesting departure at a certain time, or something that typified a certain decade, rather than go for Hockneys or Freuds or whatever.”

His favorite Brits included Graham Sutherland, William Tillyer, Leon Kossoff, and Stanley Spencer. Gavin Turk and Gilbert & George are also said to have featured in his collection.

Paul McCartney, Bowie Spewing (1990).

Photo: Paul McCartney.

Bowie was also something of an artistic muse himself. When Paul McCartney checked to see if the musician he minded the title of his 1990 canvas Bowie Spewing, Bowie told Belgium’s Humo magazine “of course not, but what a coincidence, I am currently working on a song that’s called ‘McCartney Shits.'”

One unifying thread among Bowie’s best-loved artists is a willingness to take risks. “From a very early age I was always fascinated by those who transgressed the norm, who defied convention, whether in painting or in music or anything,” Bowie told Life magazine in 1992. “Those were my heroes,” he added, listing Duchamp and Salvador Dalí along with Little Richard and John Lennon.

In addition to his proclivities as a collector, Bowie was a painter himself (he even attended art school), as well as a writer for Modern Painters. His life and career was the subject of the wildly-popular exhibition “David Bowie is,” which debuted at London’s Victoria & Albert Museum in 2013 before traveling to Berlin, Chicago, and Paris, among other cities.

Roxanne Lowit, David Bowie, Damien Hirst, and Julian Schnabel (1994).

Photo: Roxanne Lowit, courtesy Kaune, Sudendorg Gallery, Cologne.

Despite the vitriol all too often aimed at celebrities who dare to branch out into the visual arts (admittedly often for good reason—hello James Franco), Bowie refused to be pigeonholed. “I’m determined that if I want to paint, do installations or design costumes, I’ll do it,” he told the Telegraph in 1996.

As Camille Paglia wrote of Bowie in the “Theater of Gender,” her essay for the V&A exhibition catalogue, David Bowie Is…, “Music was not the only or even the primary mode through which he first conveyed his vision to the world: he was an iconoclast who was also an image-maker.”

Here are some of the artworks reportedly owned by the visionary artist:

Peter Lanyon, Inshore Fishing (1952).

Photo: courtesy the David Bowie collection.

Peter Lanyon, Inshore Fishing (1952)

Bowie lent no less than three canvases to abstract expressionist Peter Lanyon’s 2010 retrospective at Tate St. Ives. 21 Publishing, Bowie’s art publishing press, had previously released Peter Lanyon: At the Edge of Landscape, in 2000.

Damien Hirst, Beautiful, shattering, slashing, violent, pinky, hacking, sphincter painting (1995).

Photo: courtesy of White Cube © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS 2012.

Damien Hirst, Beautiful, shattering, slashing, violent, pinky, hacking, sphincter painting (1995)

“My idea of a contemporary artist is Damien Hirst,” Bowie once said.

The two artists ultimately became friends, and Bowie even teamed up with Hirst on one of the his infamous spin paintings, titled Beautiful Hallo Space-boy Painting.

Bowie bought one of Hirst’s solo efforts, Beautiful, shattering, slashing, violent, pinky, hacking, sphincter painting.

David Bowie with Peter Howson’s Croatian and Muslim (1994).

Photograph: Richard Young/Rex Features.

Peter Howson, Croatian and Muslim (1994)

In 1994, Bowie snapped up Scottish artist Peter Howson’s Croatian and Muslim after London’s Imperial War Museum, which commissioned the work, opted not to buy it due to its brutal subject matter (two men raping a Muslim woman and forcing her head in the toilet).

“Howson’s Croatian and Muslim shows what is actually happening and being done in Bosnia,” Imperial War Museum curator Angela Weight, who voted in favor of the painting but was overruled, told the Chicago Tribune. “Museums have to take bold decisions and should not go for conservatism.”

Howson, the UK’s official war artist at the time, created about 200 paintings and drawings during a trip to war-torn Bosnia that left him shell-shocked. Bowie purchased the painting, which was shown at the museum in an exhibition of Howson’s works documenting the crisis, for £18,000 ($27,000). The singer described it as “the most evocative and devastating painting,” the New York Times reported.

William Nicholson, Andalucian Homestead (1935). Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

William Nicholson, Andalucian Homestead (1935)

Bowie has lent out this sun-splashed landscape painting at least twice in the past decade. The oil painting was among 35 works by the British artist that appeared at London’s Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert gallery in 2011, and previously crossed the Atlantic in 2006 for the artist’s first American show in 80 years, held at New York’s Paul Kasmin gallery.

Patrick Caulfield,

Foyer (1973)

Photo: courtesy the David Bowie collection, © the estate of Patrick Caulfield. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2013.

Patrick Caulfield, Foyer (1973)

Yet another Brit in the Bowie collection, Peter Caulfield was the subject of a survey exhibition at Tate Britain in 2003, in which this work appeared.

“Why did David Bowie buy this painting that my dad painted?” asked the artist’s son, Luke Caulfield, on Facebook. “I think it shows a longing to escape bland post-war London and find an exotic, hidden other space where there are no rules.”

Derek Boshier, David Bowie as the Elephant Man (1980).

Photo: © Derek Boshier c/o Flowers Gallery.

Derek Boshier, David Bowie as the Elephant Man (1980)

Bowie owns some seven or eight works by Boshier, who designed stage sets for the performer’s concert tours.

The artist was so inspired by Bowie’s star turn in Bernard Pomerance’s The Elephant Man at New York’s Booth Theater in 1980 that he created an oil paint portrait based on the rehearsals.

The musician purchased a full-scale version of the work, David Bowie as the Elephant Man, while a smaller copy appeared in “Derek Boshier: Imaginary Portraits” at London’s National Portrait Gallery in 2013.

Derek Boshier, cover for David Bowie’s Lodger (1979).

Photo: Derek Boshier/EMI.

Boshier was also responsible for the cover art for Lodger in 1979. To create the image, Boshier posed Bowie on specially built trestle, photographing him from above with a Polaroid camera.

Bowie lay as if in the aftermath of a terrible fall, face contorted through the magic of stage make-up and fishing lines tugging on his lips, nose, forehead and chin. “I was blown away by David’s commitment to the project and his ability to transform himself,” Boshier told the Financial Times in 2013.

“We know [David’s] a chameleon, but he’s also an alchemist, on who can conjure magic—whether it be words, music, postures, or spaces—from thin air,” Boshier marveled of his friend and collaborator.

Erich Heckel, Roquairol (1917).

Photo: via Wikimedia Commons.

Erich Heckel, Roquairol (1917)

Bowie is also reportedly a collector of German Expressionist works, and has named himself a fan of the Die Brücke group and Fritz Lang. While artnet News wasn’t able to track down any specific works from that movement in Bowie’s collection, it’s worth noting that the cover of his 1977 album Heroes is inspired by Erich Heckel’s Roquairol.

David Bowie, Heroes album cover from graphic artist Masayoshi Sukita.

Photo: RCA.

“Heckel’s Roquairol and also his print from 1910 or thereabouts called Young Man was a major influence on me as a painter,” Bowie told Uncut magazine in 1999. He also denied rumors that the photograph was based on a Walter Gramatté self-portrait, adding, “I personally couldn’t stand Gramatté. He was wishy washy in my opinion.”