It’s the stuff of art world lore. In 1964, Robert Rauschenberg took the grand prize for painting at the Venice Biennale—the first American artist to do so—in a win that was relentlessly side-eyed. The foreign press was downright rancorous in reporting Rauschenberg’s triumph, decrying his “rubbish” art, while rumors swirled that the jury had been rigged in his favor. It was a scandal. “An extraordinary amount of hostility,” Rauschenberg later recalled, “was created by my good fortune.”

Did the U.S. game the Venice Biennale? A new documentary, Taking Venice (2024), has answers. Directed by art critic and filmmaker Amei Wallach, it unearths archival reports and footage, and features interviews with key players in a bid to untangle the machinations behind Rauschenberg’s victory.

“I didn’t just want the story to be, ‘Oh, look what America did,'” Wallach told me over the phone. “I wanted to show the complexities of all these different people with different ambitions and different motives, working towards the same end.”

Perhaps the one with the biggest motive here was the U.S. government, which at this time was years deep into what has been termed the Cultural Cold War. Around 1950, the U.S. commenced a sprawling cultural propaganda effort to spread the good word on liberal democracy, while neutralizing the lure of Communism. Exhibitions and magazines, artists and writers, and universities and museums were all leveraged to foreground such American hallmarks as freedom of expression and individualism. Most infamously, the covert campaign, with the help of the Museum of Modern Art, did much to burnish the international standing of Abstract Expressionism.

Taking Venice makes plain that America’s involvement in the 32nd Venice Biennale, by way of the United States Information Agency, was a political project. As artist Michelangelo Pistoletto reflected in the film, the Gran Premio “was the crown American politics was missing.”

Cue a cast of art-world figures including the then-director of the Jewish Museum, Alan R. Solomon, and curator Alice Denney—both appointed U.S. commissioners for the 1964 Biennale—and dealer Leo Castelli, who jointly set about finessing the nation’s entry in Venice. “We wanted to win the prize and show that we had some great art,” Denney said in the documentary. “And we thought with Rauschenberg, we had a very good chance.”

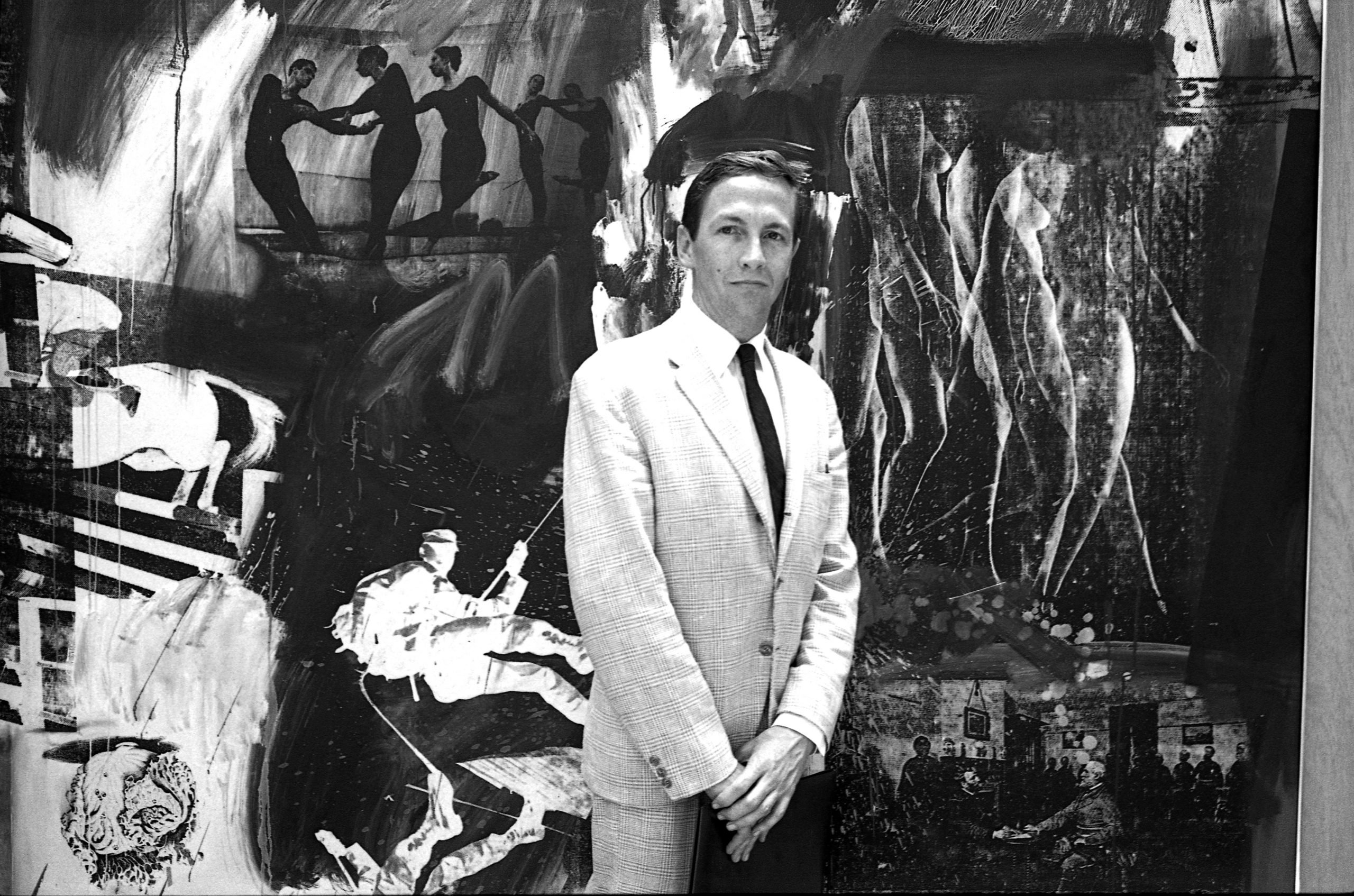

Robert Rauschenberg exhibition at the Venice Biennale, 1964. Photo: Shunk-Kender © J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute.

The choice of Rauschenberg was an unlikely—even risky—one. At this point in his career, the artist had begun incorporating found objects into his paintings and pioneering “combines” in conceptual, often absurdist, ways that defied formal composition. The art establishment took its time warming up to him, or in the artist’s words: “I was considered a clown by nearly everyone else.”

Still, Solomon, who organized the artist’s 1963 retrospective at the Jewish Museum, saw promise in Rauschenberg. “He really believed Rauschenberg was showing a new way to make art,” Wallach said. “Back in the late ’50s and ’60s, we were just coming out of our self-congratulations about Abstract Expressionism. This was the opposite: it was showing people that there was yet another way to be free.”

Transporting Robert Rauschenberg’s Express (1963) at the XXXII International Biennale of Art Exhibition, Venice, 1964. Photo: Ugo Mulas © Ugo Mulas Heirs. All rights reserved.

In fact, Solomon’s belief in Rauschenberg was such that he thought the pavilion on the Venice Giardini site too small to exhibit the artist’s work. While pieces by Kenneth Noland were displayed at the official venue, Solomon picked the empty U.S. consulate building to show four Rauschenberg canvases, alongside works by John Chamberlain, Claes Oldenburg, Jim Dine, and Frank Stella. Solomon even extracted a verbal agreement from the Biennale that artists on view at this “precedent-setting annex outside the grounds,” as he called it in a letter, would still be eligible for the grand prize.

The agreement did not hold. At the last minute, the commissioners learned that the external exhibition disqualified the artists from the competition. Their solution? Transferring Rauschenberg’s outsized canvas from the consulate to the Giardini in a rented barge. Denney oversaw the trip along Venice’s canals and the hanging of the paintings at the U.S. pavilion. It was a dramatic maneuver, recreated in the climax of Taking Venice—but none more dramatic than the reaction from the media, which called out America’s “stealth move” as “skullduggery” and “treason.”

Recreation of the 1964 transport of Robert Rauschenberg’s work in Venice canals for exhibition at the Venice Biennale. Still from Taking Venice. Courtesy of the filmmakers.

But the gambit worked. Bolstered by the soft power of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company—which performed at the event amid scenography designed by Rauschenberg just days before the jury voted—and the harder-driving tactics of Solomon, the U.S. claimed the Golden Lion. Controversy followed. “They just weren’t used to what Americans were doing at that point, which was marketing and PR,” said Wallach of the media’s reception. “But everybody was trying their best to do that.”

Taking Venice is just as concerned with Rauschenberg’s journey after the Biennale. Critic Calvin Tomkins recalled how the artist, upon clinching the grand prize, instructed his studio to destroy all his silkscreens so as not to repeat himself. And in the following decades, Rauschenberg’s art grew increasingly engaged with social shifts and political turmoil—from the Civil Rights Movement to the Vietnam War—just as he sought cultural exchange through his Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange project. The resulting picture is of an acutely forward-looking artist who wasn’t just deserving of the Biennale’s top award, but built upon and looked beyond it.

Robert Rauschenberg, Buffalo II (1964). © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation.

To Wallach, that Rauschenberg’s win was engineered doesn’t take away from his gift; rather, it bespeaks a long-lost era when America invested art with world-shaping power. “The U.S. thought art was so important that it could actually win hearts and minds,” she said. “There was huge optimism and belief in art. The government thought it mattered; the artists thought it mattered.”

“They got it right,” historian Philip Rylands said in the film about America’s bet on Rauschenberg. “How they did it was another matter.”

Taking Venice opens nationally on May 17 at the IFC Center in New York and on May 24 at Laemmle Theaters in Los Angeles.