Few abstract artists were as rigorous about form and design as Piet Mondrian. So the Dutch painter would likely not have been too pleased to learn that one of his paintings has been hung upside down for the past 75 years.

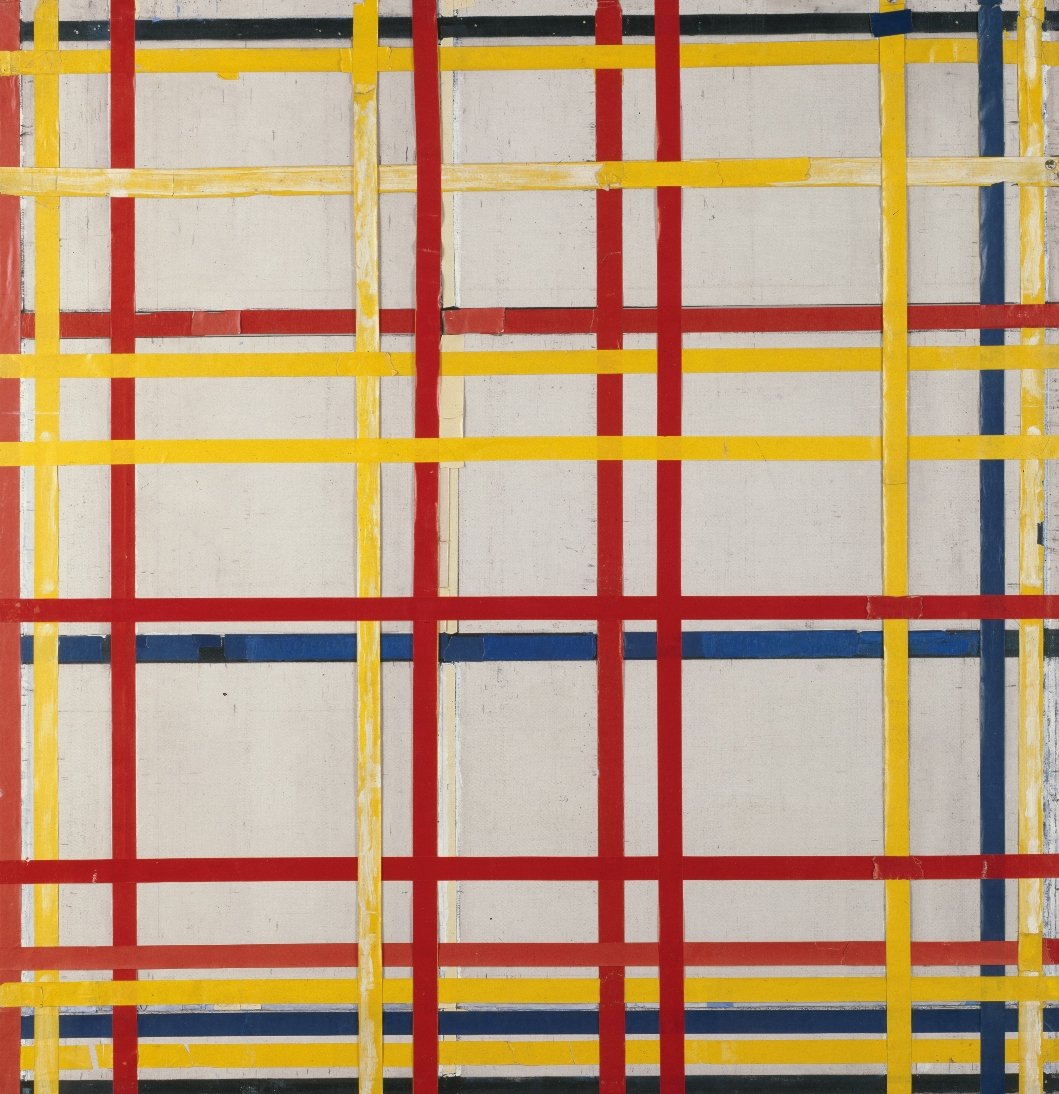

The composition of New York City 1 (1941) is a grid of yellow, blue, black, and red stripes. Experts now think that the canvas may have been flipped as early as 1945 when it was installed at MoMA, an error that may have resulted from how it was packaged and transported.

The artist was unfortunately not around to correct the presumed mistake. He died one year earlier in 1944.

The faux pas was only discovered this year by curator Susanne Meyer-Büser as she was planning “Mondrian. Evolution,” a new exhibition dedicated to the modernist at the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen K20 in Düsseldorf, Germany. The work entered that museum’s collection in 1980.

It will be the highlight of the forthcoming exhibition but, as Meyer-Büser told a press conference yesterday, when she undertook research into the work’s past she found a photograph of it in the artist’s studio from 1944. The image showed the painting propped up on an easel the opposite way than it has always been seen since.

Flipping the composition would mean that the tight grouping of lines traditionally found at the bottom was really meant to be at the top—matching the orientation of a very similar work, New York City (1942), held at the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

With these clues in mind, the curator also studied the tape on the canvas and found that the way it is layered suggests that Mondrian must have worked from top to bottom. The edges at the bottom (which has until now been understood as the top) are therefore less neat and in one place half a centimeter is missing.

This piece of physical evidence was found to be the most compelling by Meyer-Büser’s team of restorers, who now consider her claim to be true.

Still, despite Meyer-Büser’s discovery, the adhesive painting will be exhibited the same way it has been since 1945 for fear of causing damage to the fragile work.

The curator considers the wrong hanging to be just part of its long history. “Perhaps there is no right or wrong alignment at all?” she suggested to Germany’s Monopol Magazin.