The fabled Library of Alexandria is one of the most famous structures of the ancient world, up there with the Pyramids of Giza, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, and other architectural wonders described by long-dead poets and philosophers.

And yet, despite its notoriety, we know terribly little about the Library—how it was made, how big it was, or even when it was destroyed. In fact, we have only one surviving description of the complex, passed down to us from the Greek historian and geographer Strabo, who visited the Egyptian coastal city between 30 and 25 B.C.E.

“The Museum is part of the palaces,” he wrote in Geographia. “It has a public walk and a place furnished with seats, and a large hall, in which the men of learning, who belong to the Museum, take their common meal. This community possesses also property in common; and a priest, formerly appointed by the kings, but at present by Cæsar, presides over the Museum.”

Modern readers may wonder why Strabo refers to the Library as a museum. He does so not because the Library housed ancient artifacts, though many of its books were undoubtedly old, even when compared to the institution itself. Rather, the word originally denoted any place of learning and human ingenuity associated with the Muses, the Greek sister-goddesses of art, science, and divine inspiration.

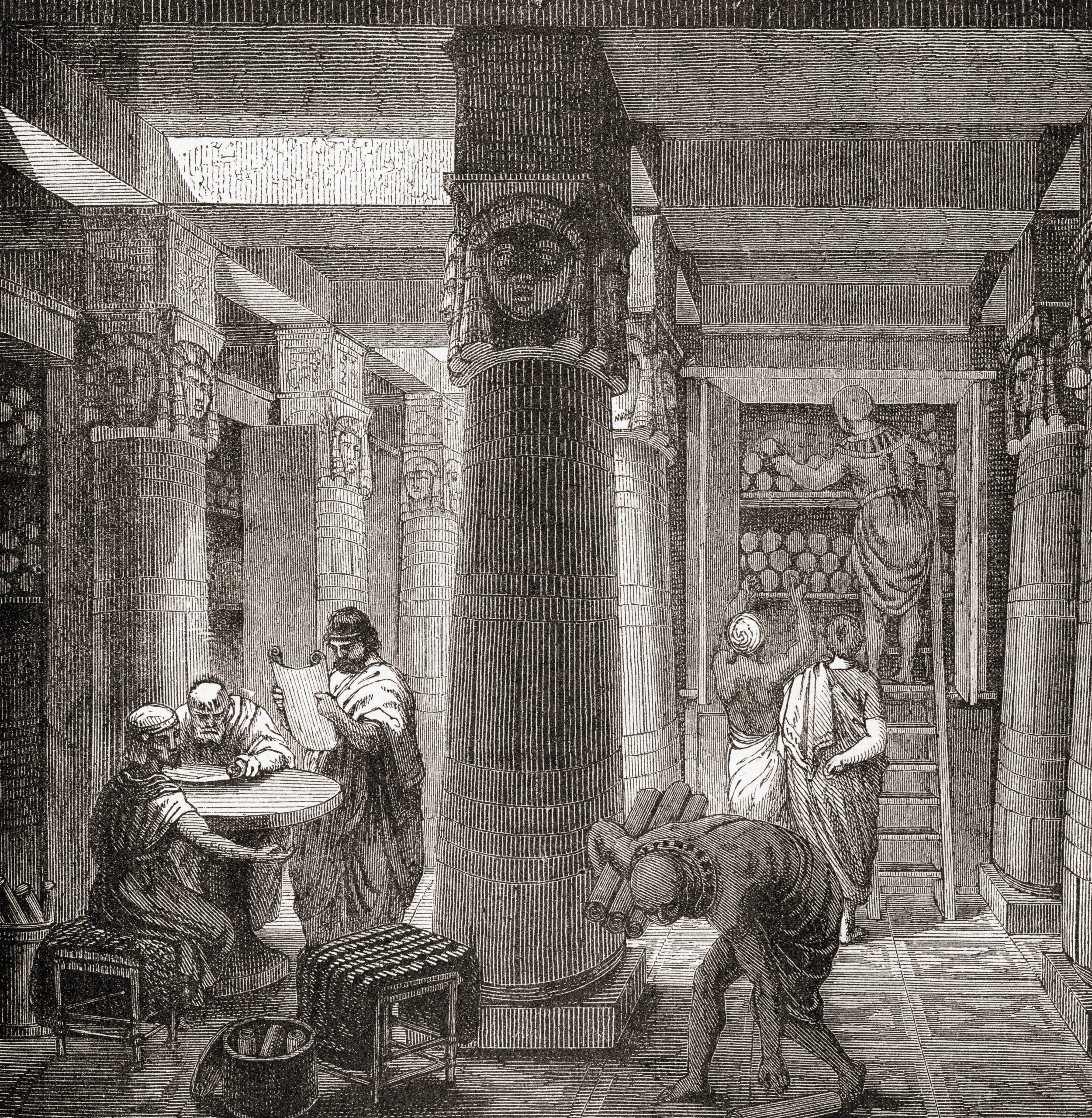

Illustration of Ptolemy I planning the construction of the Great Library at Alexandria. Photo: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

While we don’t know the exact year the Library of Alexandria was erected, its construction is typically attributed to the reign of Ptolemy I and Ptolemy II. These pharaohs were successors of Alexander the Great, the Macedonian conqueror who brought much of Asia Minor, Egypt included, under his control. Because of their Greco-Macedonian origin, historians suspect that many of the books inside the Library of Alexandria would have been written in Greek.

Just how many books were kept inside the Library is another enduring mystery. An unnamed Jewish writer from the 1st century B.C.E., visiting Egypt around the same time as Strabo, claimed that the complex contained “all of the books in the world,” a statement which, while almost certainly hyperbole, speaks to the Library’s unparalleled size.

In the same piece of writing, the author goes on to state that the Library contained anywhere between 200,000 and 500,000 books, a testament to the wealth of ancient literature that has been lost to time.

Fortunately, we know a little bit more about how the Library of Alexandria acquired its books. Galen, a Greek physician who served Marcus Aurelius among other Roman emperors, wrote that Ptolemy (we don’t know which one) “was so eager to collect books, that he ordered the books of everyone who sailed there to be brought to him. The books were then copied into new manuscripts. He gave the new copy to the owners, whose books had been brought to him after they sailed there, but he put the original copy in the library with the inscription ‘a [book] from the ships.’”

Caesar Defeats the Troops of Pompey, from The Story Caesar and Cleopatra, Flanders, c. 1680. Woven at the workshop of Gerard Peemans, after a design by Justus van Egmont. Detail from a larger artwork. Photo: Getty Images.

Legend has it the Library was destroyed when Julius Caesar invaded Egypt to hunt down his ally-turned-enemy, Pompey the Great. Involving himself in a civil war between his lover, Cleopatra, and her brother, Ptolemy XIII, the dictator burned down the ships in Alexandria’s bay, starting a fire that, according to the Roman poet Lucan, spread to the rest of the city:

“Nor did the fire fall upon the vessels only: the houses near the sea caught fire from the spreading heat, and the winds fanned the conflagration, till the flames, smitten by the eddying gale, rushed over the roofs as fast as the meteors that often trace a furrow through the sky, though they have nothing solid to feed on and burn by means of air alone.”

Though long accepted as fact, modern historians have found contradictions in ancient sources casting doubt on Caesar’s culpability. For example, one of the dictator’s lieutenants, Aulus Hirtius, said that “Alexandria is almost completely secure against fire,” as its buildings were largely devoid of flammable materials such as timber.

Burning books in the Library of Alexandria (1st century B.C.E.). Photo: Getty Images.

The description offered by Strabo, who visited Alexandria some 20 years after Caesar, suggests that if the Library of Alexandria was damaged or destroyed, it was quickly rebuilt. Actually, contrary to popular belief, the library was destroyed and repaired several times over the course of history, including (so historians believe) as recently as 642 C.E., when Muslim Arabs invaded Egypt.

To compensate for the loss of the great library, the city of Alexandria did construct a new one: the $220 million Bibliotheca Alexandrina, with construction starting in 1995 and stretching until 2002; the late Irish singer Sinéad O’Connor performed at the opening ceremony. While the original housed mostly Greek manuscripts, its spiritual successor, constructed with funding from France’s Bibliothèque nationale, contains some 500,000 French manuscripts, making it the world’s sixth-largest Francophone library.

The symbol wall of the Bibliotheca Alexandrina Library by the Mediterranean in Alexandria, Egypt. Photo: Planet One Images / UCG / Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

The Bibliotheca Alexandrina is hardly the institution that its ancient predecessor was; the number of its holdings is far outpaced by institutions like the British Library, the world’s largest, boasting a collection of some 200 million items. But still, there’s plenty of room to grow: the new library contains shelf space for some eight million volumes.

And what’s more (hello, Strabo!), it contains no fewer than four museums.

The Hunt explores art and ancient relics that are—alas!—lost to time. From the Ark of the Covenant to Cleopatra’s tomb, these legendary treasures have long captured the imaginations of historians and archaeologists, even if they remain buried under layers of sand, stone, and history.